0 :00 – 0 :09

The video begins with an inscription, « PLAY ». The screen turns black.

0 :09 – 0 :13

VHS colour bars appear.

0 :14 – 0 :22

The screen turns brown.

0 :22 – 0 :37

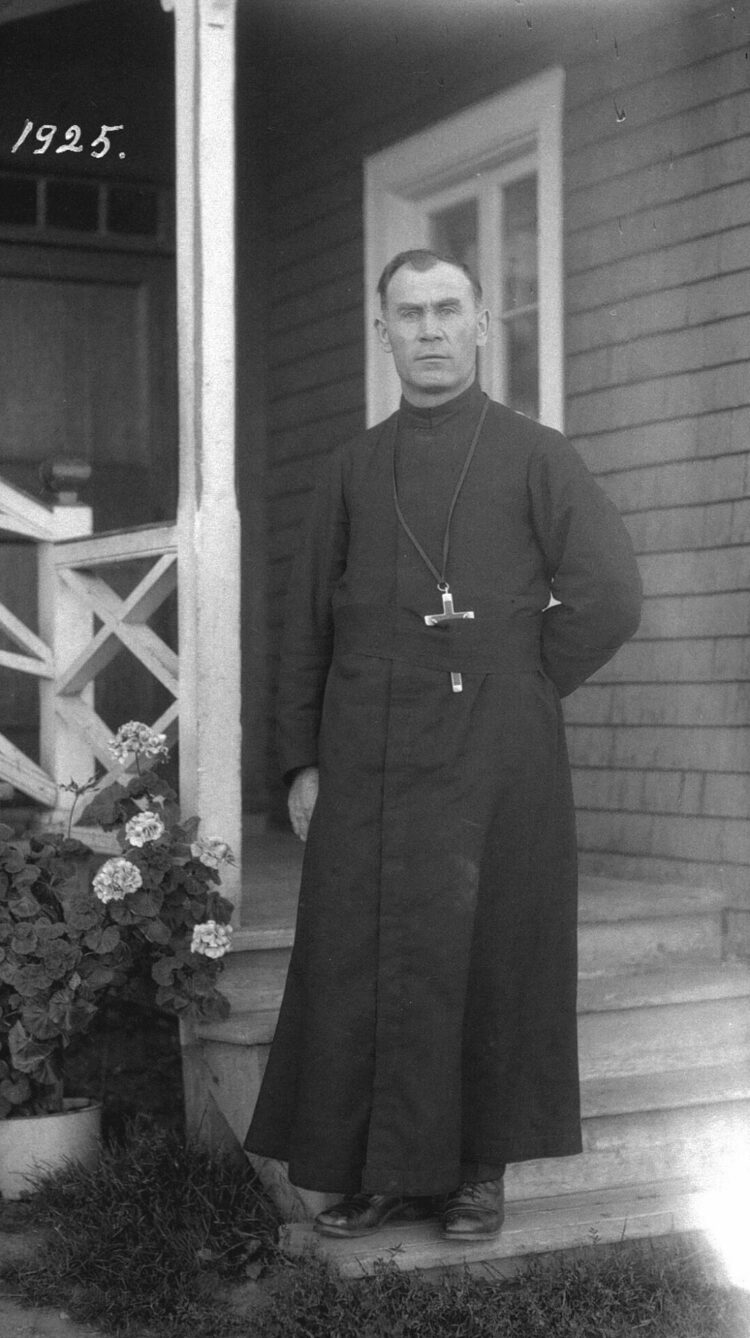

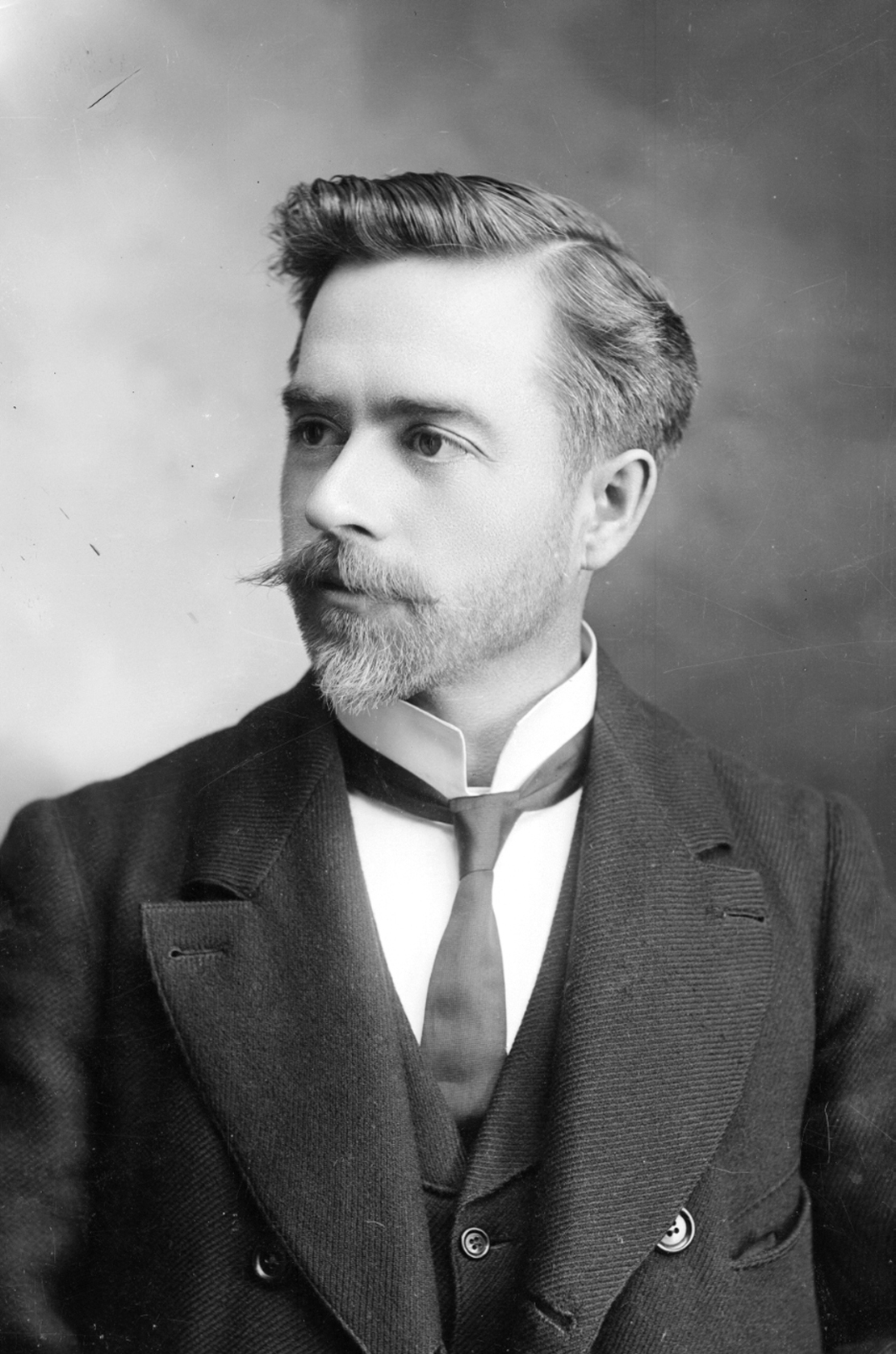

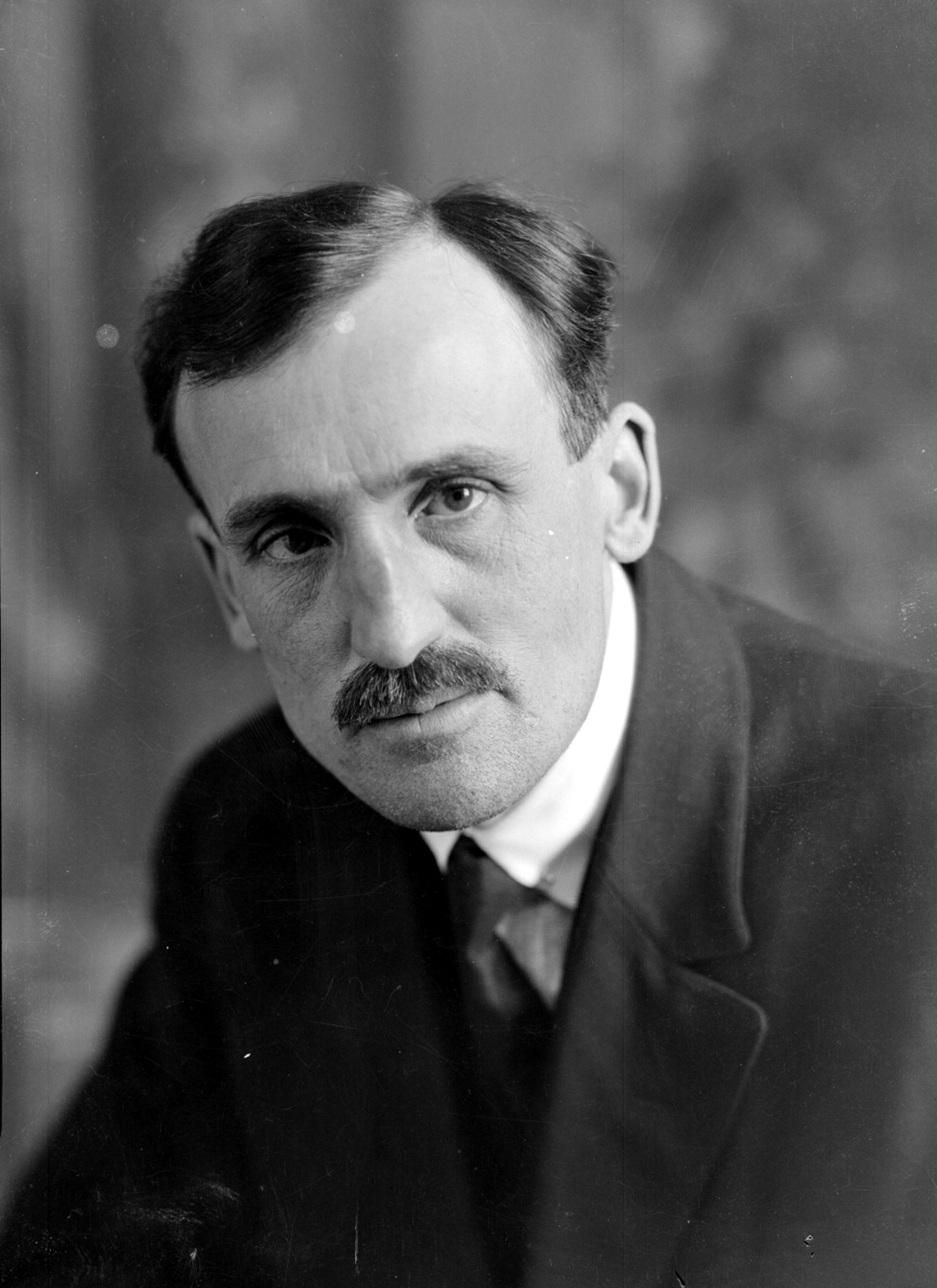

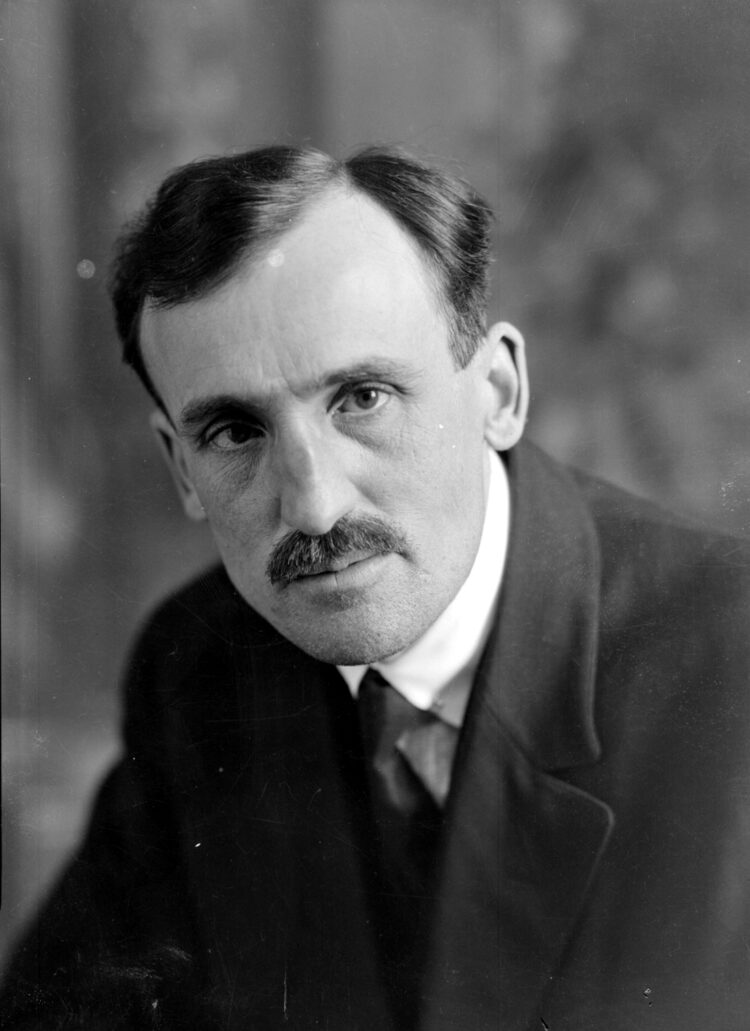

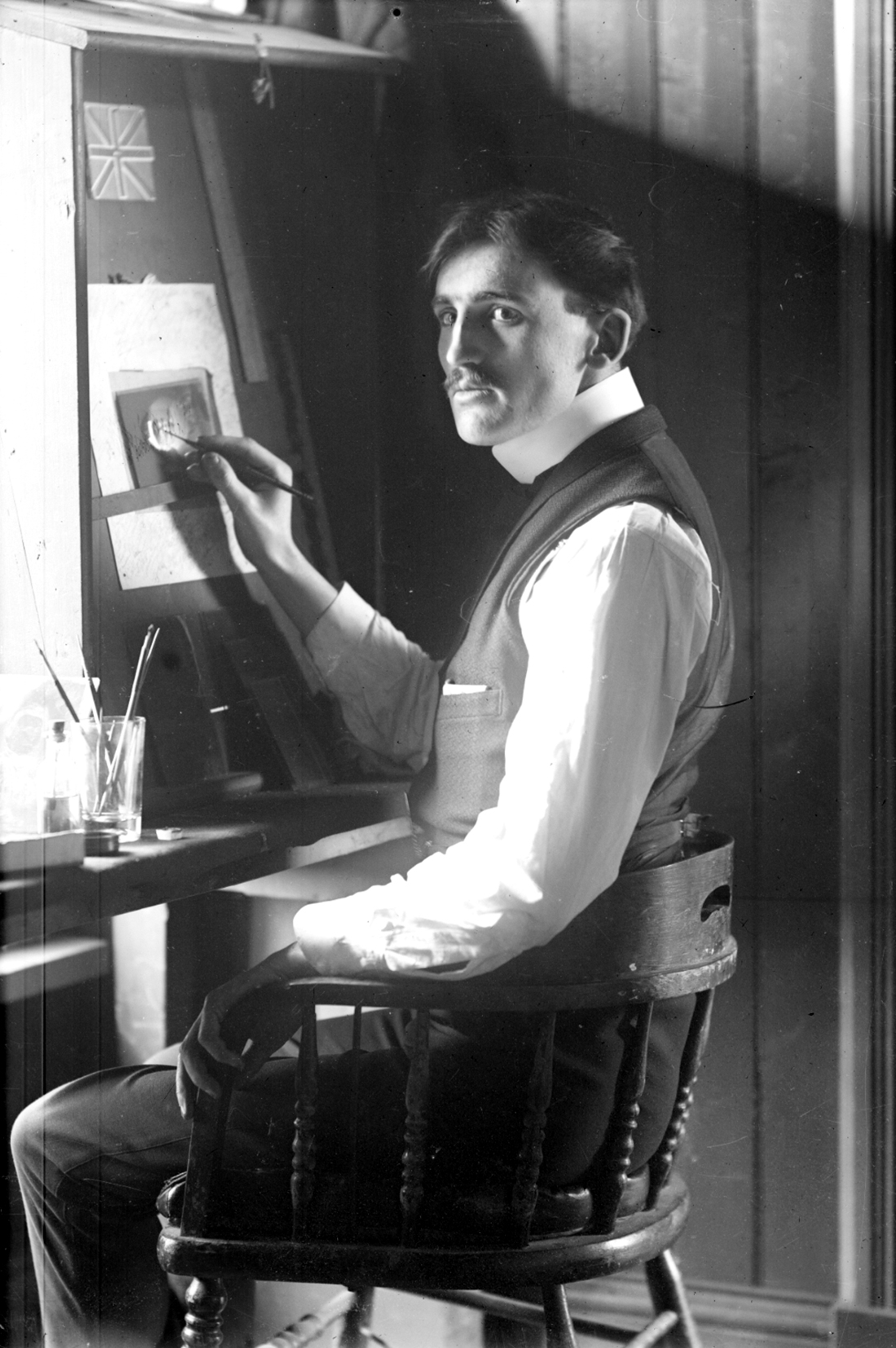

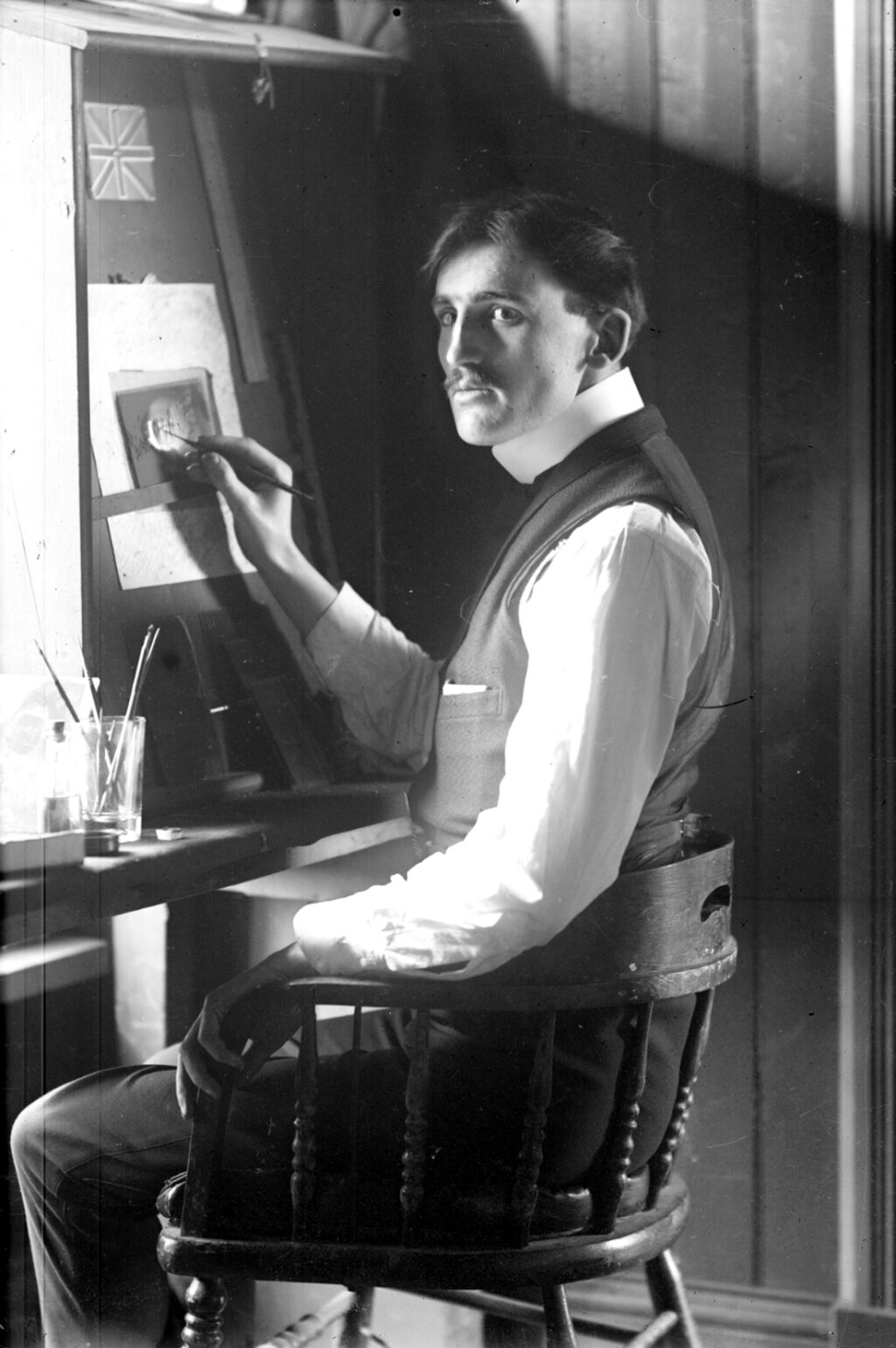

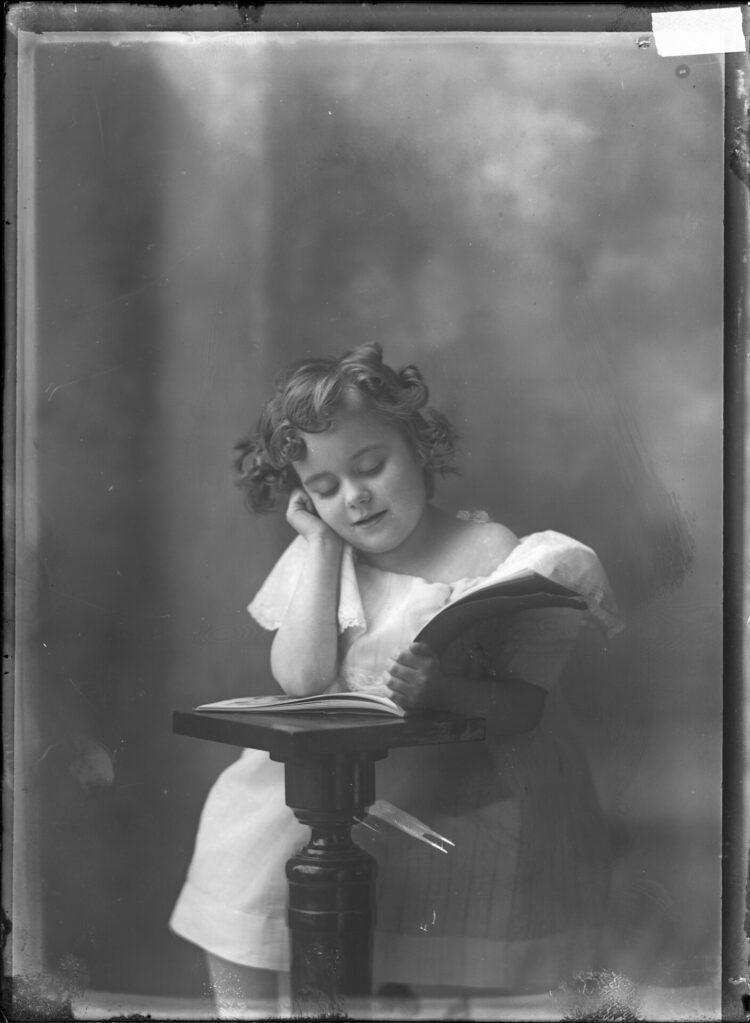

A portrait of a young Marie-Alice Dumont appears, first as a negative which gradually becomes a positive.

0 :37 – 0 :53

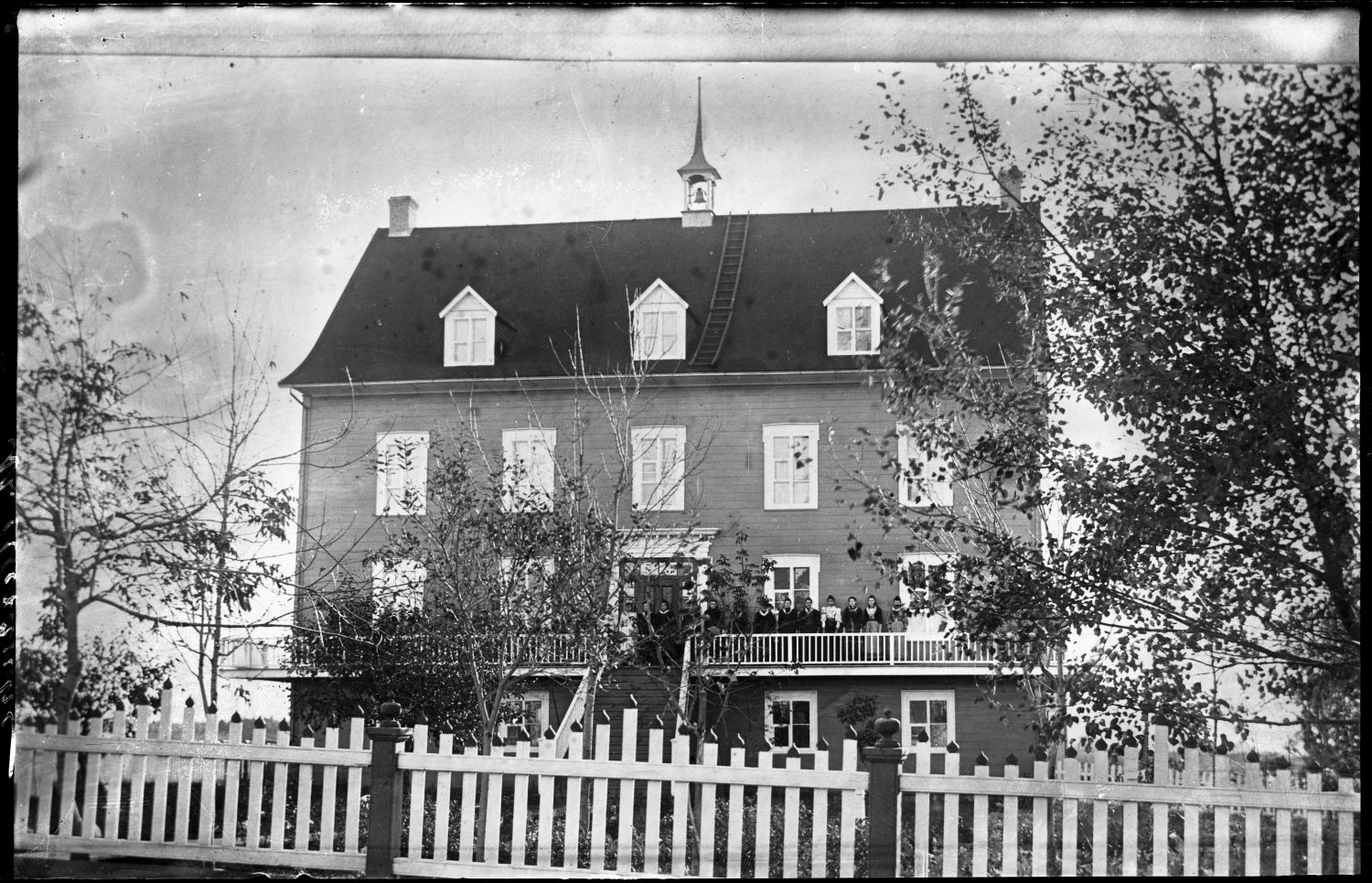

Shot of a table on which there is a studio portrait of Marie-Alice Dumont, a small bouquet of flowers, and the shadow of a tripod on which a camera is placed. A title is displayed, « Marie-Alice Dumont photographe, St-Alexandre. » (Marie-Alice Dumont photographer, St-Alexandre)

0 :53 – 2 :40

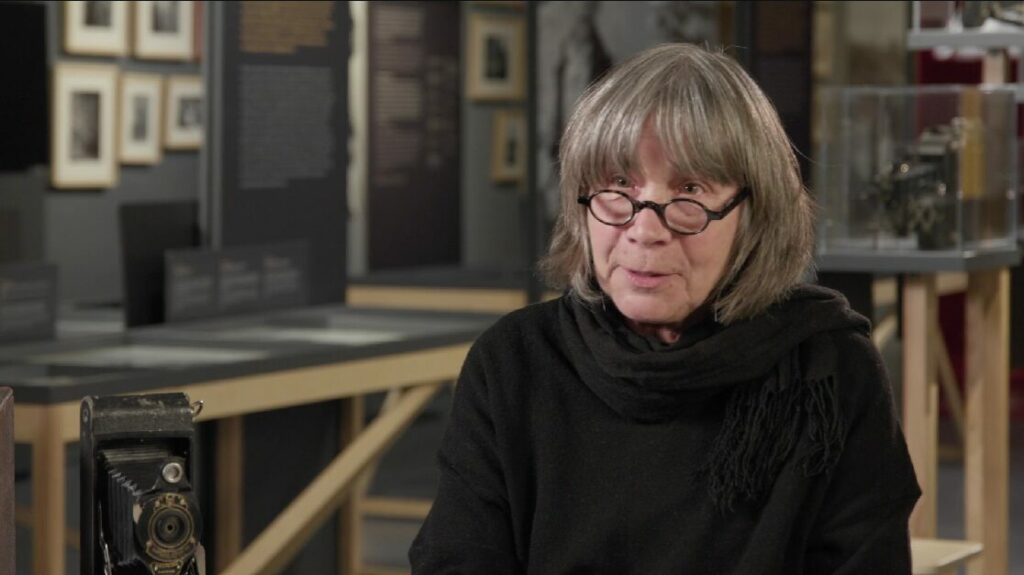

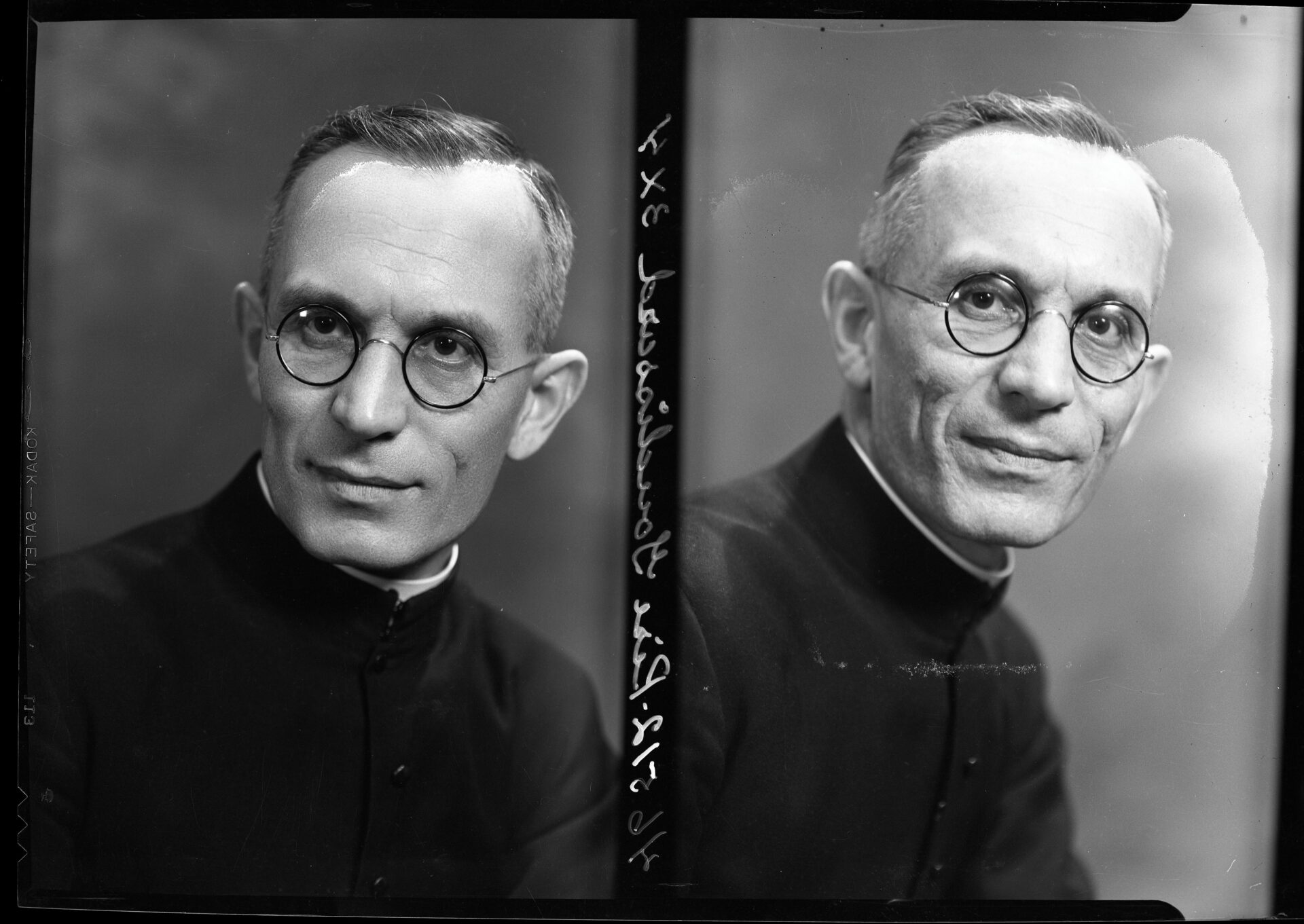

Close-up on Marie-Alice Dumont’s face. She is an elderly woman with grey hair and glasses. She addresses the interviewer who is behind the camera:

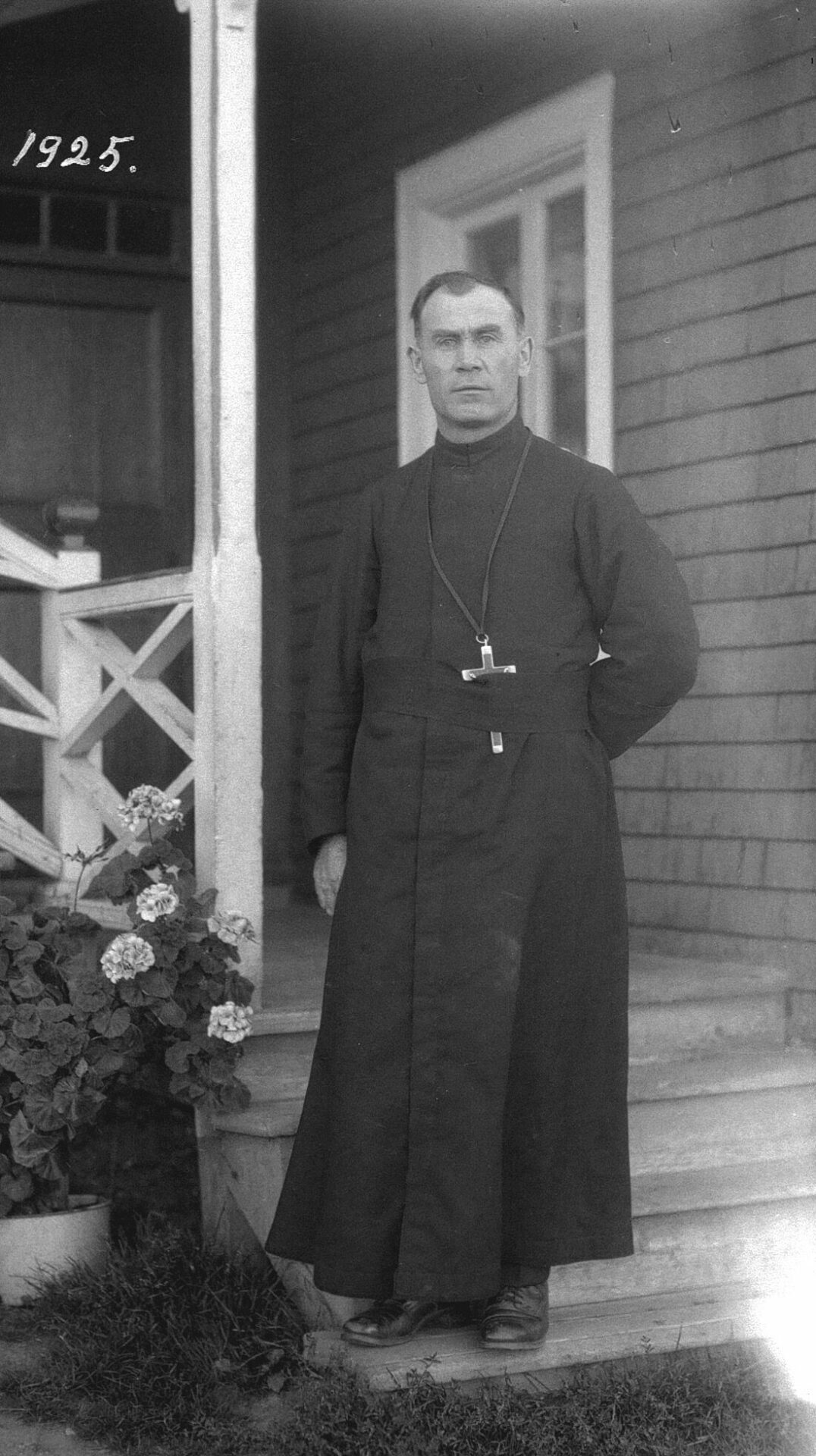

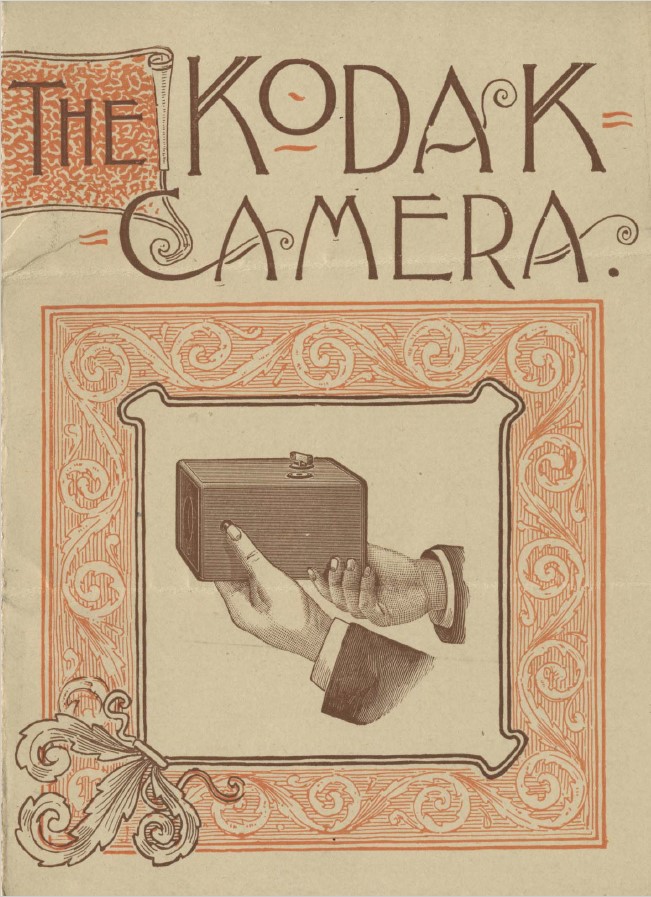

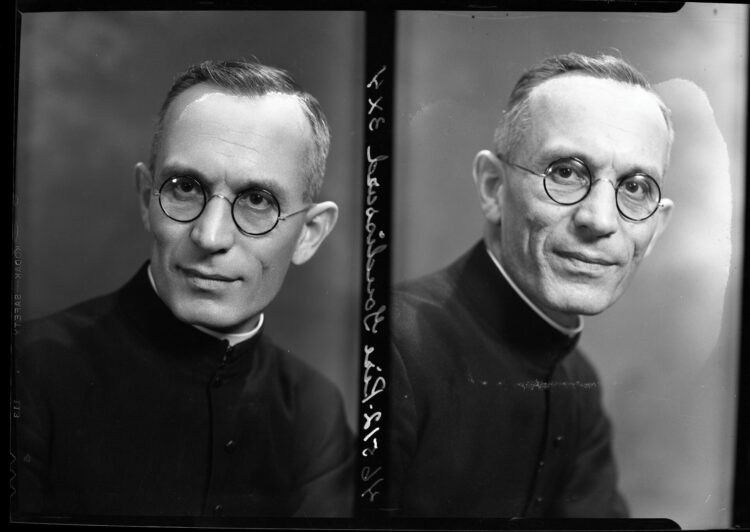

I thought about that because it was my brother, who is a priest, you see, who told me about it. I think I was… I had no work, you see! I wasn’t able to do heavy work, and I was sick, and I wrote to him, and I told him I wanted to make a little money, and I didn’t know what to do. It needed to be something that wasn’t difficult, not hard. He sent me a small Kodak, and all these little trays, and everything that was needed […] to start, you see! And a book, an amateur book, an amateur book. He told me: « Study that. » And he said: « […] When I go on vacation, » he said, « we’ll try that, developing films. » In the upper part of the summer kitchen, I had a darkroom there, there was no window, so that worked out well. We started that. Some time later, the lamp caught fire haha! The paper burned. But it didn’t matter, […] we bought another one. And we did what we thought […] I started taking little photos like that, with my Kodak, to practice. And then, he, in Sainte-Anne de La Pocatière, he was teaching class, he is a clergyman. He was teaching class, and he had films sent to me. The little boys posed with little Kodaks, and he would send them to me. That’s what I practiced with.

2 :41 – 2 :51

Shot of the interviewer who is seated. She speaks to Marie-Alice Dumont:

When you started taking photos, you were in the house on the 5e Rang. Where were you taking your photos? Where were you developing your films at that time?

2 :52 – 3 :33

Back to a shot of Marie-Alice Dumont, who answers the questions:

Oh! […] I wasn’t very well set up. I was in the upper part of the summer kitchen. But I had a bedroom in the house. In winter, I did that in the bedroom. I would pull down a blind and I did that in the evening. And I would work for a while, and then I would go to bed. I was too tired, I was too useless. Haha!

Still on the same shot of Marie-Alice Dumont, we hear the interviewer’s voice, who asks Dumont a question:

And then you moved into your house in Saint-Alexandre.

Marie-Alice Dumont answers:

In 1926, we moved. My father bought a house in the village there. And he had everything repaired inside. And in the spring, he had the basement redone, and he had the a big window redone there, the big bay window there, that’s what I used for light.

3 :34 – 3 :53

Footage taken with the video camera shows the bay window viewed from outside the house, then Dumont’s house viewed from the front. We hear the interviewer’s voice at the same time, then Marie-Alice Dumont’s.

The interviewer says:

When you talk about the big window, it’s a kind of skylight you had, because there was no electricity, I think, when you moved?

Marie-Alice Dumont answers:

There was no electricity, we were three years without electricity. […] But it didn’t matter, I only took pictures during the day. And for developing films, it was with the sagelight, in the darkroom. It was dark, it was bright only by that little lamp.

3 :54 – 5 :08

Back to a close-up shot of Marie-Alice Dumont. We hear the interviewer:

Over the course of your career as a photographer, how many different cameras did you have?

Still on the same shot, Dumont answers:

Oh! I had, to begin with, I had the little amateur camera, besides that I had postcard size [camera], I bought [a] postcard size. After that I bought 8×10, [a] 8×10 size [camera]. A big Kodak. And I bought a big, a lens for 130 dollars. We had it brought over from England. A traveler had it brought to me. […] And it took good pictures well, it worked out well with my indoor Kodak, I installed it in my indoor Kodak and the outdoor one. And you saw the portraits, the big portraits there? That’s it. It worked just fine. I sold that with my Kodaks. That’s why now I have nothing left. Haha!

Still on the same shot, we hear the interviewer:

When you were taking indoor photographs and outdoor photographs, was it the same camera?

Marie-Alice Dumont answers:

Oh yes, they were the same ones! But the indoor one was another special one, that I had set up on a special table with adjustable height, that I adjusted with a crank. I raised it and I lowered it. And you could… adjust the length too. We set it to the length we wanted. And it took good photos.

5 :09 – 5 :41

Shot of the shadow projected on a wall of a camera installed on a tripod.

5 :42 – 7 :04

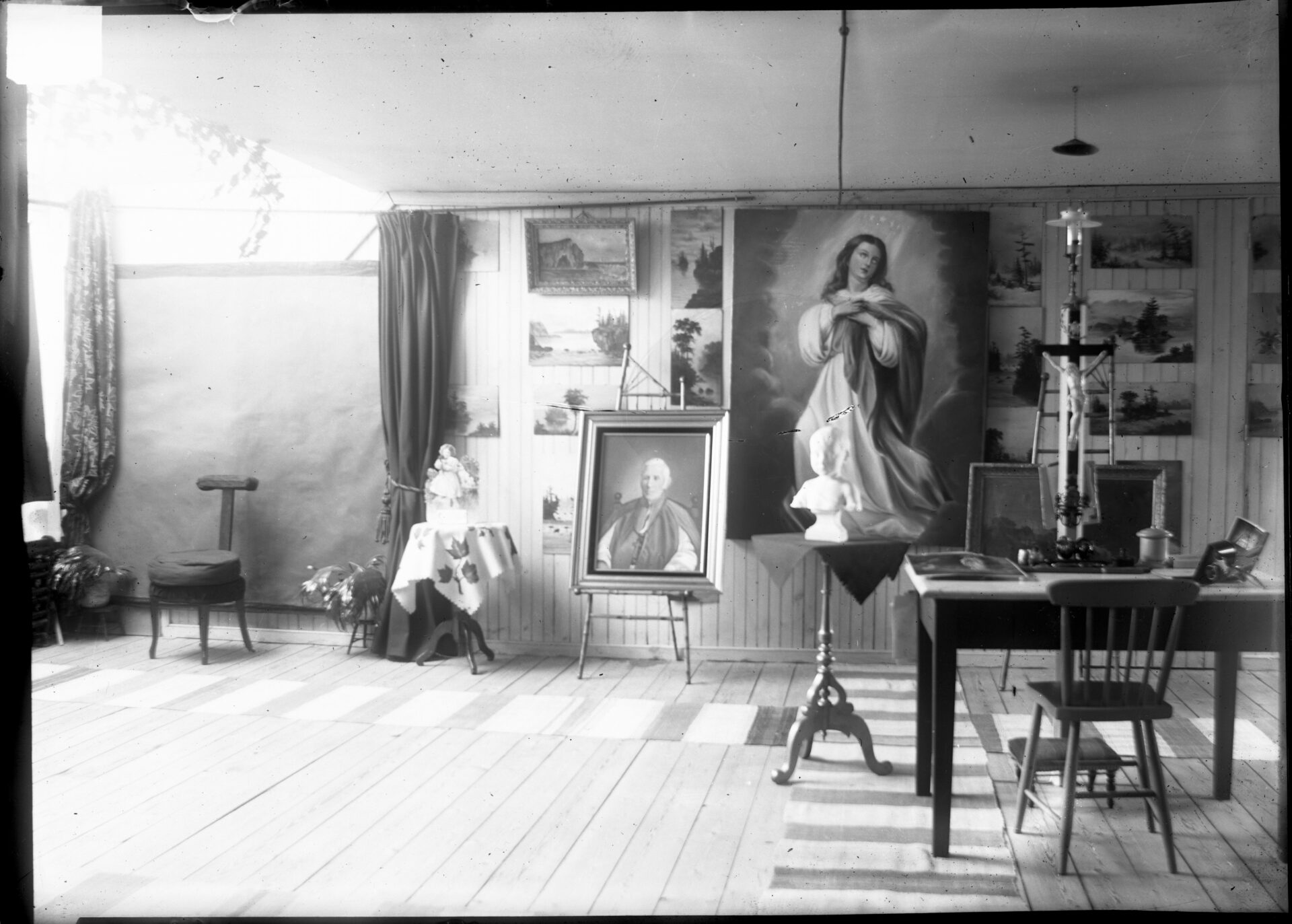

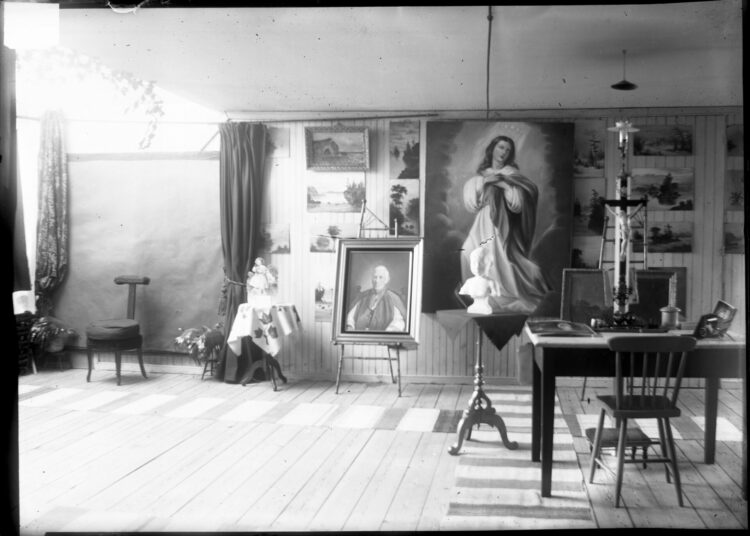

Back to a slightly less close shot of Marie-Alice Dumont, who speaks:

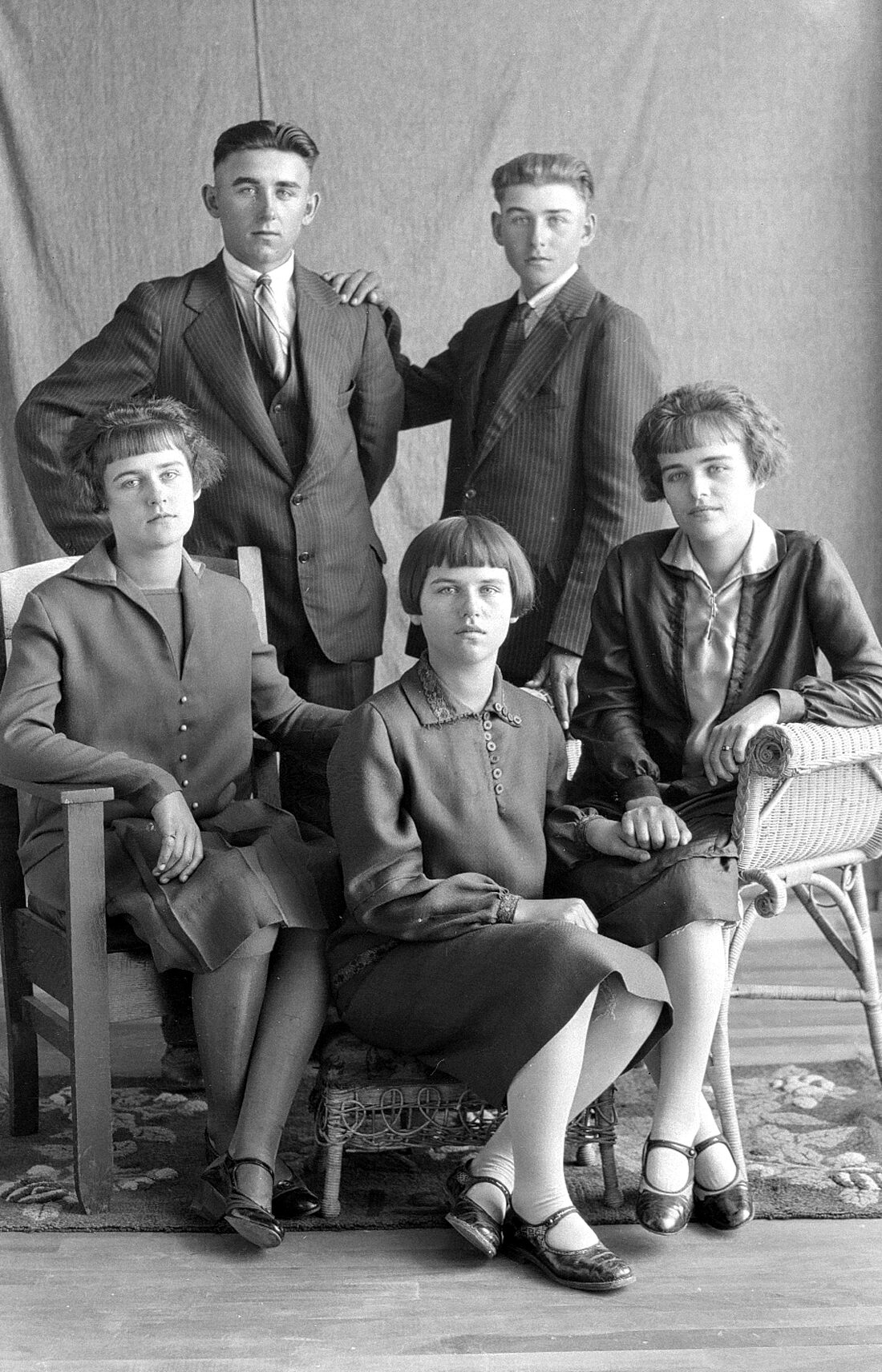

In my studio I had, in the backdrop, there was a big painting. I bought that from Lévis, from a photographer who died. It was his sister who had it, she was a widow and she was selling it. I bought everything. A big painting that covered the entire width of my studio. My studio was a big… it was a nice apartment. And there was a closet here, in the back. A big closet to store my things in. And that backdrop was there, and there was another smaller backdrop that I put in front when I was only posing one person. I wanted to pose the upper part, you see, just the bust, or married couples. I didn’t put the big… uh. The big backdrop was in the back, and that didn’t bother anything. And you know, I had another one there, it was on a stand. I had a white sheet that I put over it, to light up the side of the face, you see. That was on the other side. And I had a bench. I had a big bench made, this long, with a backrest. And people would sit on it, only one person. And the backrest had trimmings on it, it was nice. Moreover I had chairs. A rush-bottom chair, made in straw [inaudible]…

7 :04 – 7 :13

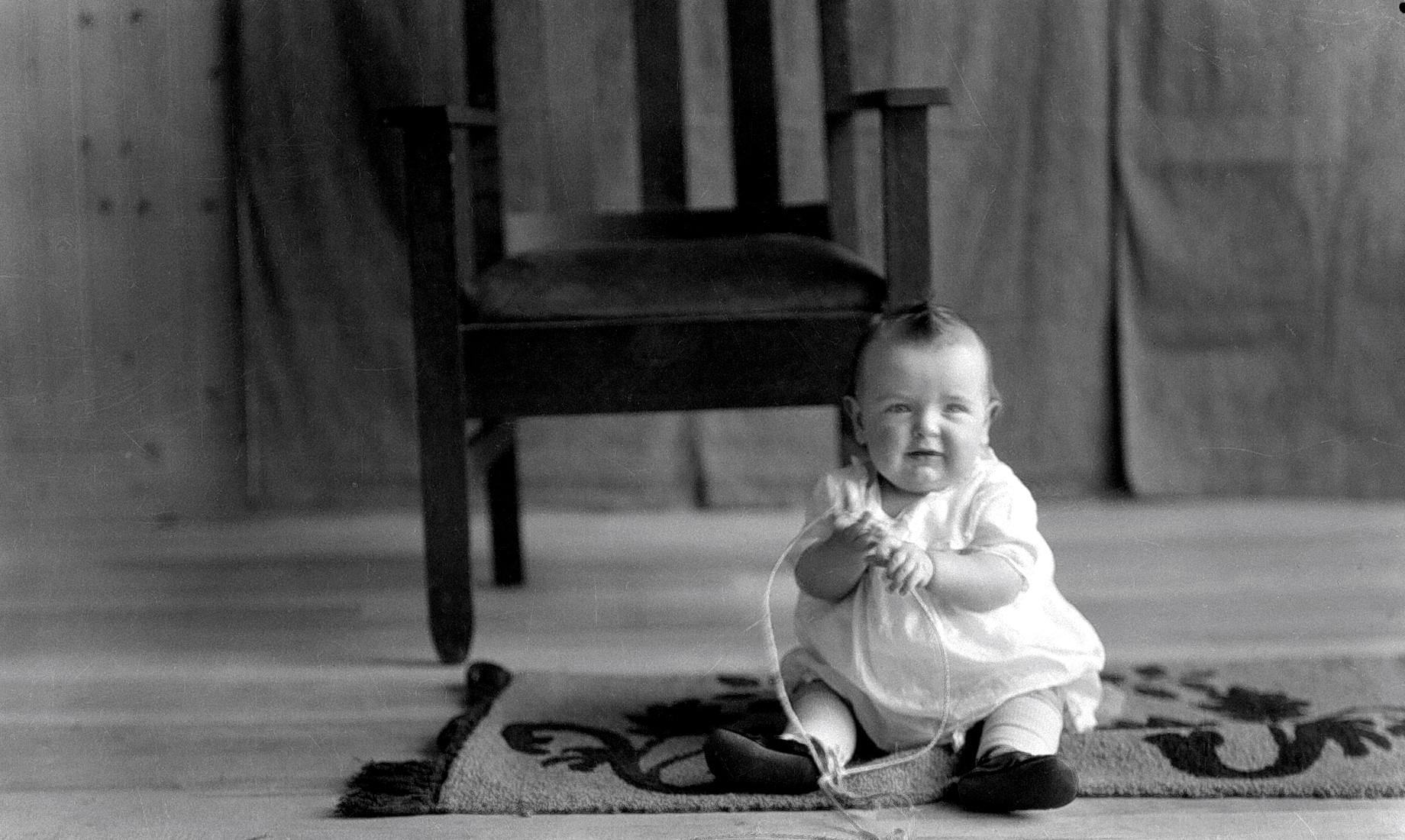

A portrait of a baby posed lying on the long rush-bottom chair with a backrest that Dumont was talking about.

During this time, Dumont continues her explanations:

… with a backrest there, a beautiful backrest there. And, you know, it was always the same. I posed the children on it, sometimes, when things were rushed, you see.

7 :14 – 7 :25

A multi-generational portrait of three Dumont women and a baby is shown. During this time, Marie-Alice Dumont continues her explanations:

I had another armchair, then another item, it had arms, arms on each side. And I posed people on it. I have some, I think, here. I think I have one.

7 :26 – 8 :14

Back to a shot of Marie-Alice Dumont, who continues:

I don’t know if I had anything else… And when I posed families, I had a little bench. I had a little bench made that I put in front for the people, for the children. And another one. When I bought it, I also had a little bench. Very low, you see, to have them sit on it. I had everything I needed! Haha! And my Kodak was on that side [Dumont points to her right]. And there was a double door there, and when space was lacking, I moved back into the side hallway, and I took photos from there, and sometimes I went all the way into the kitchen, all the way into the dining room. The dining room was in the back there, and I moved back all the way into the dining room to take photos of big families. I just had to keep the door out of the way.

8 :15 – 8 :25

A multi-generational portrait including four women and a baby is shown.

8 :25 – 8 :35

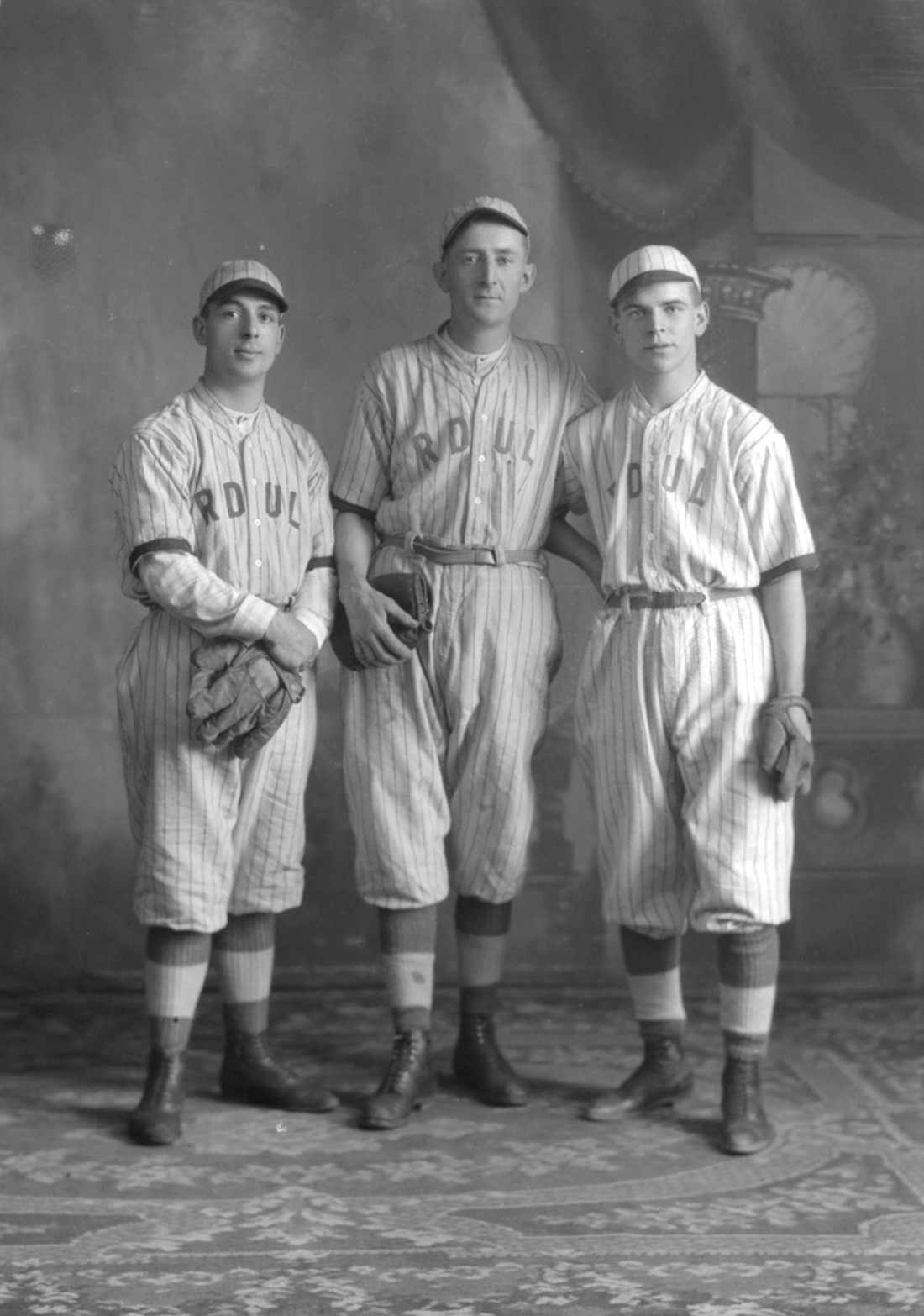

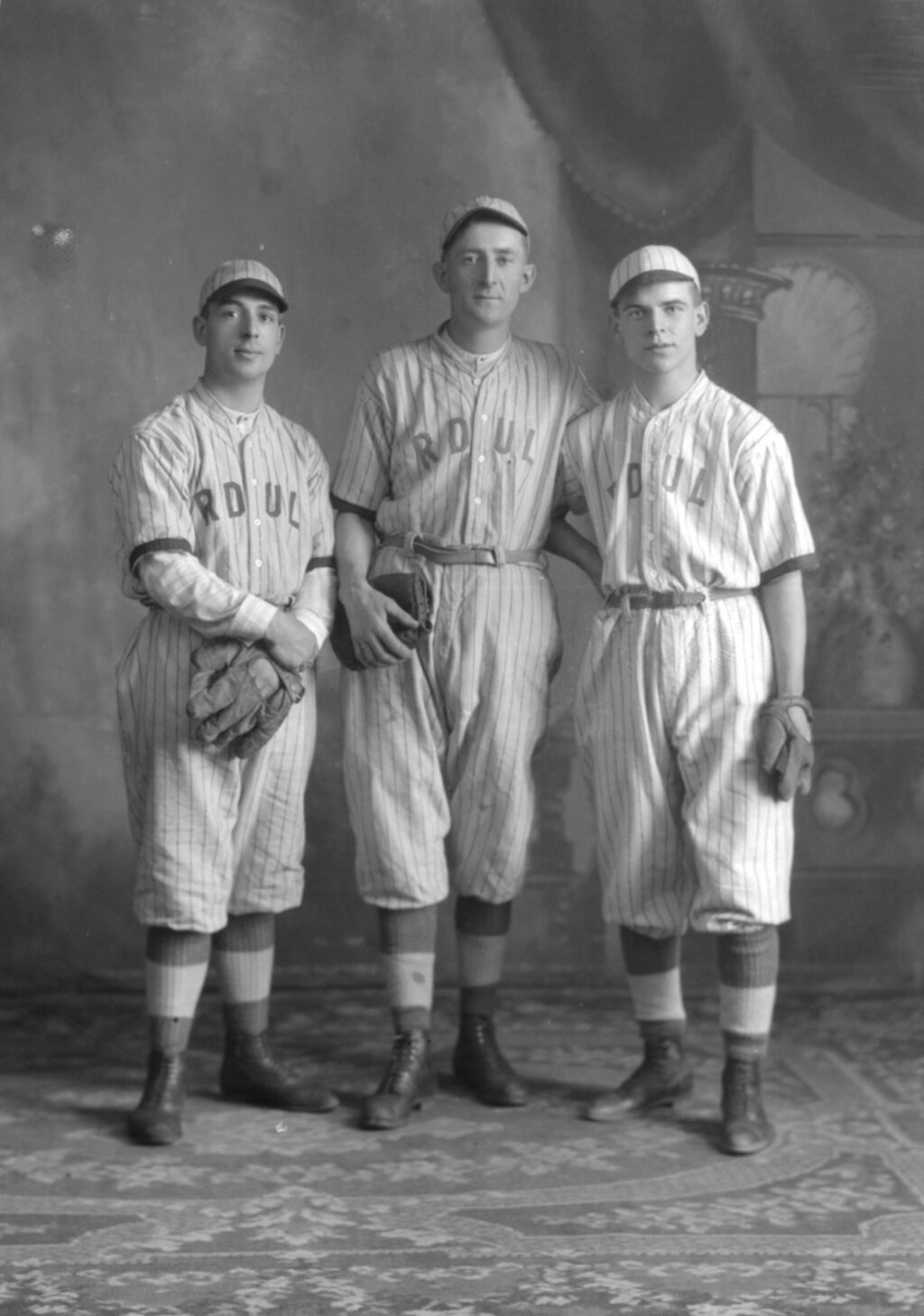

A negative portrait of three men is shown, which flips to a positive.

8 :35 – 8 :41

A portrait of a young girl in communion attire is shown, kneeling at a kneeler and next to which is a lily placed on a stool.

8 :42 – 8 :51

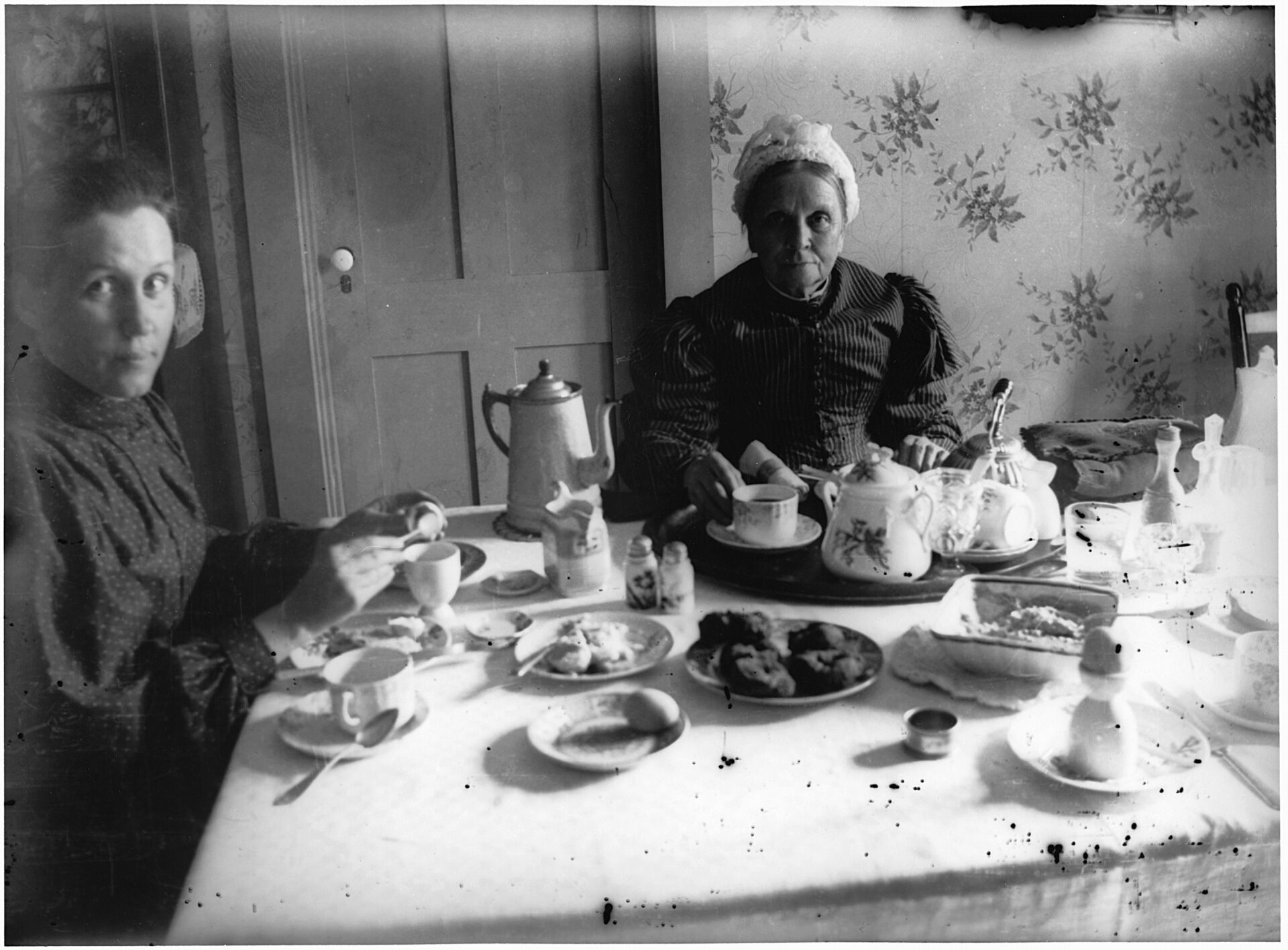

A portrait of a fairly old couple in a domestic environment is shown.

8 :52 – 8 :57

A portrait of a baby in a wicker carriage is shown.

8 :58 – 9 :08

The same multi-generational portrait of Dumont women as before is shown. This time, the negative transforming into a positive is shown.

9 :08 – 9 :35

Back to a close-up shot of Marie-Alice Dumont, who speaks:

The other time I photographed my father and my mother, I don’t remember where it was… And my father, I showed that to my father after it was finished, I showed the picture to my father. And I told him « look how well my mother is posed. » He says « yes! » Oh yes, he says « she is well posed. » But he says, he says « Look! » He says: « Look, I’m in it too! » Hahaha! That was when they were sleeping, I think.

9 :35 – 9 :39

The photo from the anecdote Dumont is telling is shown. It is a portrait of her parents asleep at the dining room table.

We still hear Dumont speaking:

That was when they had fallen asleep. They had fallen asleep at the table.

9 :40 – 9 :57

Back to a close-up shot of Marie-Alice Dumont.

He was at the end of the table, he was eating at the end of the table, my mother was next to him, facing the other way. And they were… Let me see… I’m losing my memory… haha! Uh… they were talking together after they had finished eating. They were talking together.

9 :58 – 10 :15

Back to the portrait of Marie-Alice Dumont’s parents asleep at the table. Dumont continues to speak during this time.

My father was leaning on the table, and my mother was next to him on a rocking chair. And all of a sudden she fell asleep. And he saw it, he saw [that she] was sleeping, and he did the same, he fell asleep too. And I said « Look at that! It’s a good time to pose them! »

10 :15 – 10 :49

Back to a close-up shot of Marie-Alice Dumont, who continues to recount the same anecdote:

And then we hurried, we took the dishes off the table near them, and we lowered the blinds on the windows […]. And I got my Kodak out and I took a photo. As soon as I finished posing them, my mother woke up. She says, she says « What are you doing there? » Haha! I said « Nothing! You’ll see, it’s not much! »

The interviewer then asks Dumont a question:

Were they proud to have a photographer daughter?

Dumont answers:

Oh! They must have been. Haha!

The interviewer continues:

There were surprises like that from time to time…

Dumont answers:

Yes, yes! Well you understand, don’t you!

10 :50 – 10 :54

Shot of the interviewer, who asks Dumont a question:

And at what time of the day did you mainly work?

10 :54 – 11 :21

Back to a close-up shot of Dumont, who answers the question:

I got up after lunch, and I was good to work a little in the afternoon. And when someone arrived, I worked for a while. Because people mainly came in the afternoon, you see. Rarely in the morning. When they came for the films, my sister was there to receive them, she didn’t need me. That’s how it went. I did… I did photography in the afternoon.

11 :21 – 13 :03

Change of shot of Marie-Alice Dumont, but slightly farther away. The interviewer asks her a new question:

And you could finish working very late at night…

Dumont answers the question:

Yes! And sometimes during the night, well, people would pass… they would pass through the parish and they would stop to drop off a film for me to develop and they wanted to have it back the next day when they returned. And I had to hurry to do that, in the evening. And it had to dry. I had to… dry the film, and after that I had to do the portraits… do the, yes… the portraits during the night and let them dry… I had a dryer, I bought… I had bought a dryer, a nice big dryer, and you put that on a metal sheet [inaudible]. And I heated that up… Uh… When it was dry you put them in a press, you put them in a press, and the next morning I only had to mail them.

The interviewer asks Dumont a new question:

Is that why you sometimes got up late, because you didn’t have long nights?

Dumont answers:

Well yes! I was forced to go to bed late because I worked late and the next day I was tired and I had to go to bed. In the morning I wasn’t disturbed much. That’s why I went to bed in the morning. I had breakfast and I went back to sleep for a bit. And there were times when I couldn’t. Haha!

The interviewer asks Dumont another question:

Well, basically the job of a photographer was demanding, because people didn’t have a schedule, they could come anytime.

Dumont elaborates:

No! No no… There was no schedule for that. They came when they were ready. Haha!

The interviewer continues:

And any day too!

Dumont answers:

There weren’t always clients, no. There were days with no customers. No, it depends… especially on Sunday after mass [people would come to the studio]. People were in the village, you see, at the church. And they would come to have their photos taken after mass, they would come to pick up… They would come to pick up their portraits after mass, the ones from the parish, you see.

13 :03 – 13 :06

Shot of the interviewer, who is listening to Dumont, whose voice is still heard:

One time I was tired, I was very tired. I posed people…

13 :06 – 13 :43

Back to a close-up shot of Dumont. The shot gradually gets a little closer as Dumont continues her explanations:

… after mass, on Sunday. And we were supposed to go have dinner somewhere, at a relative’s house. And [inaudible] came to get me, and my brother, I think, was helping. And they arrive and I was in the middle of taking a photo, or… I don’t know… anyway, they had to wait. And after I finished, I was worn out and my face was red with exhaustion. I told them « Go get in the car! » And so they went, and I washed my face during that time. But my brother saw me and he said « What are you doing? » Haha! I said « I’m washing my face, it feels good! » That revived me, and then I was fine.

13 :44 – 14 :18

Back to a shot of Marie-Alice Dumont, but slightly farther away. The interviewer asks Dumont a question:

And in a year, Miss Marie-Alice, I don’t know if it’s easy for you to estimate this, how many photos could you take?

Dumont answers the question:

How many photos could I take? Uh, I can’t say how many. But it kept me busy when, uh… when I was able to do it.

The interviewer continues the discussion:

Let’s say in the good years when you were still relatively healthy, how much could you do? A thousand photos?

Dumont answers:

Do how many what?

The interviewer repeats:

A thousand photos, in a year?

Dumont answers:

Oh! Per year? Oh! Maybe yes… maybe I could make a thousand…

14 :19 – 15 :48

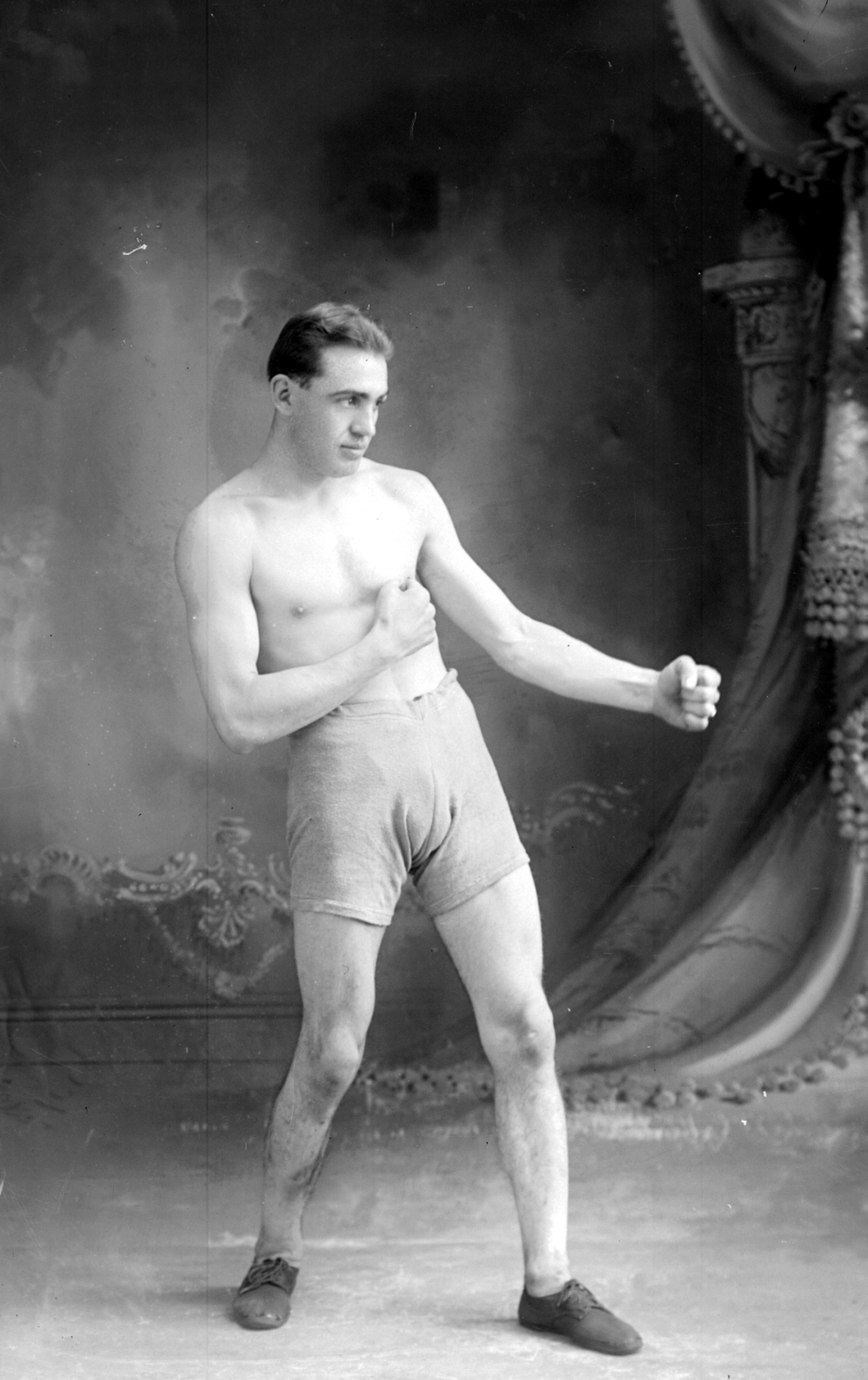

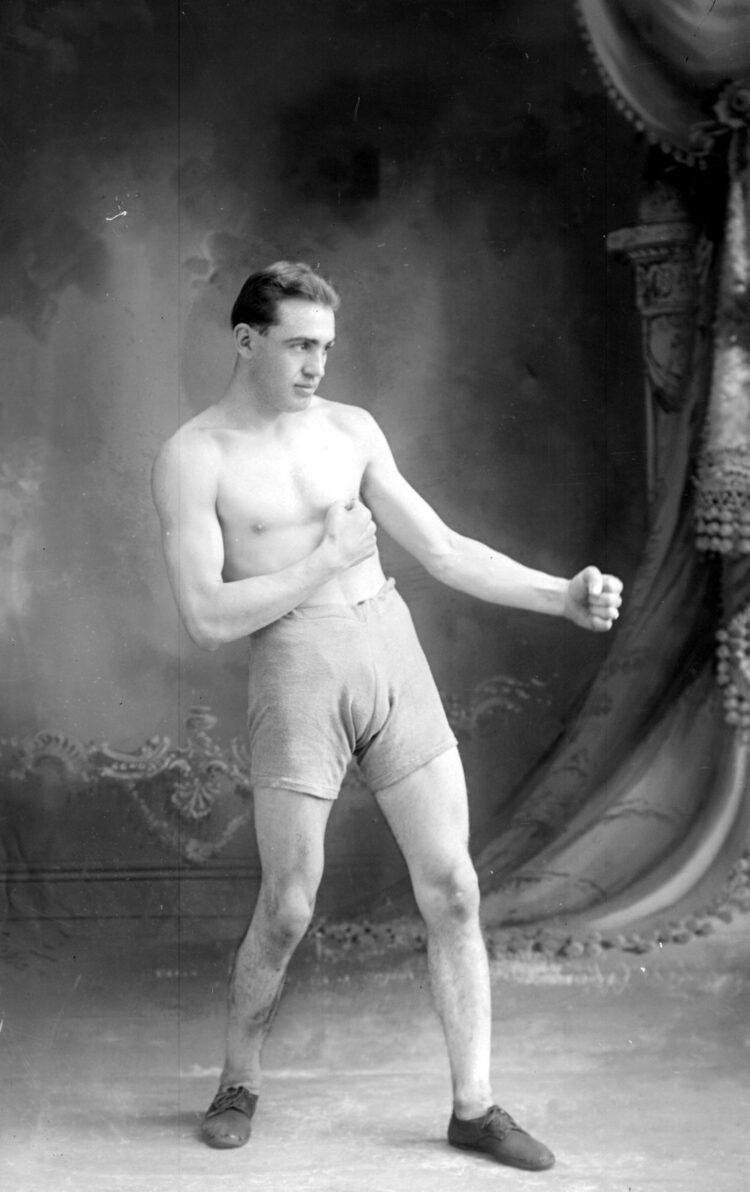

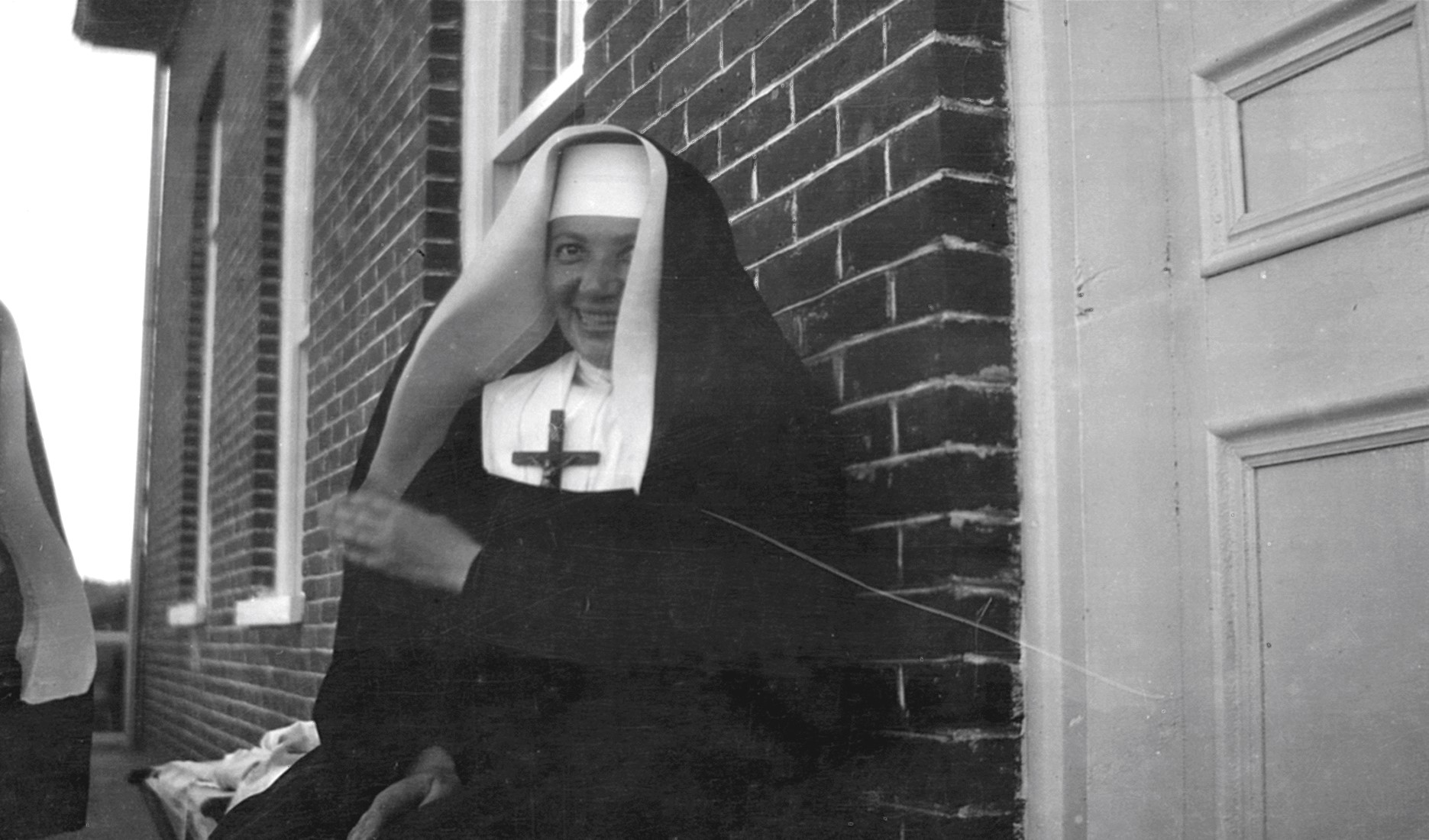

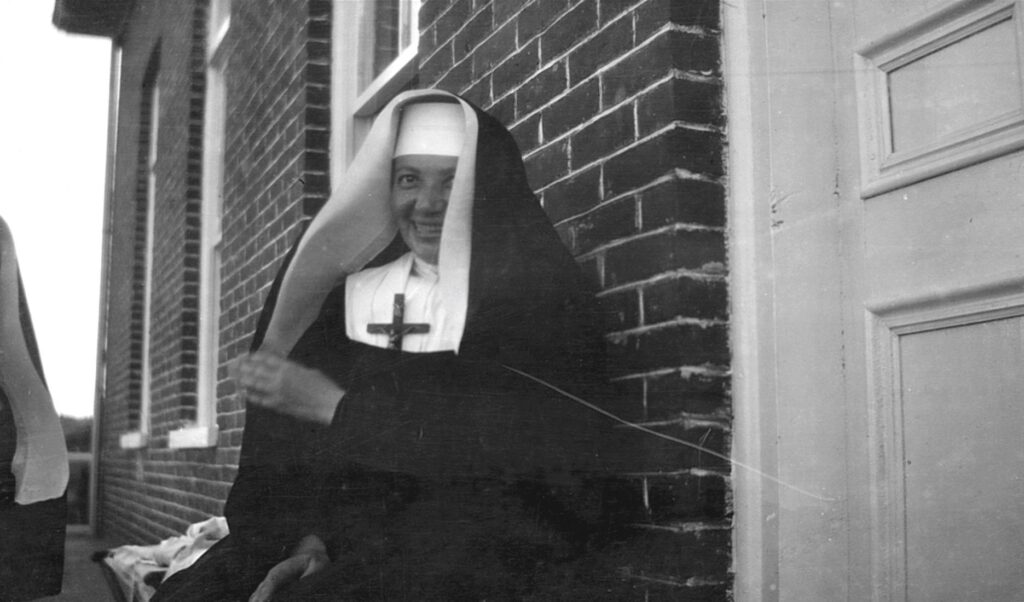

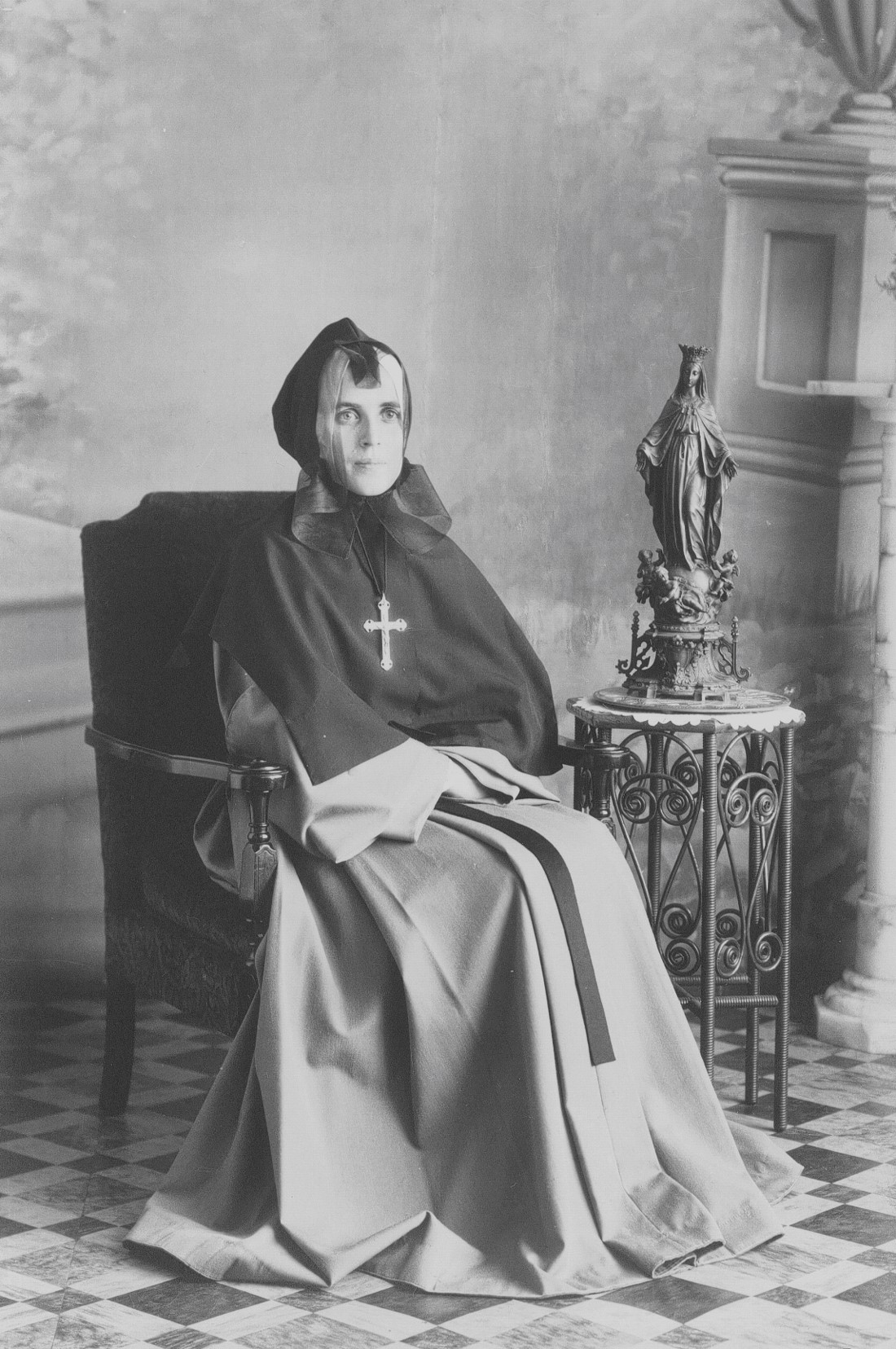

Photographs taken by Marie-Alice Dumont are shown one after the other. They are all presented in positive form and in negative form.

A first photo shows Marie Pelletier (Dumont’s mother) and Origène Dumont (the photographer’s nephew) making bread in the family kitchen. A second shows Marie-Louise Dumont (the photographer’s sister) at the loom. A third shows Marie Pelletier working at the warping board. A fourth shows Uldéric Dumont (the Dumont’s father) and Origène Dumont sitting on the steps of the porch of the family home. A fifth shows a group of six men on a farm, each standing next to a cow. A sixth photograph shows a street in the village of Saint-Alexandre-de-Kamouraska. A seventh shows a rang (rural road) located just outside the same village. An eighth image is displayed, which is not, however, a photograph by Marie-Alice Dumont, but rather a video showing the current appearance (as of 1981) of the rural road represented in the previous photograph.

15 :48 – 16 :45

Back to a close-up shot of Marie-Alice Dumont. We hear the interviewer asking Dumont a question:

How much did a photo cost in 1940?

Dumont coughs a bit, then answers the question:

In 1940? In 1940 it was… that was later. 1940, when I had, yes… uh… It depends! It depends on the size. Postcards: 1 dollar! 1 dollar a dozen.

The interviewer repeats:

For postcards?

Dumont continues:

Postcards. And the others, uh, the others that were larger, well, they were more expensive. But it wasn’t expensive [inaudible]. And there were small films, the development of small films. Four cents. The development, uh… 10 cents per film, developing a film. And four cents per little portrait. That came out to, that came to 42 dollars… 42 cents per film. And after that you put it in the mail, and the mail cost four cents. It wasn’t expensive! Haha!

16 :45 – 17 :03

Another shot on Marie-Alice Dumont, but very close. The interviewer asks:

And when did you stop your career, what year was that?

Dumont answers:

In ’61 [1961].

The interviewer continues:

And why did you stop taking photographs?

Dumont answers:

Because I had to have surgery. And I was all alone at home. My girls [her assistants] had left! And I had to go have surgery, and when I came back I wasn’t able to continue.

17 :03 – 17 :44

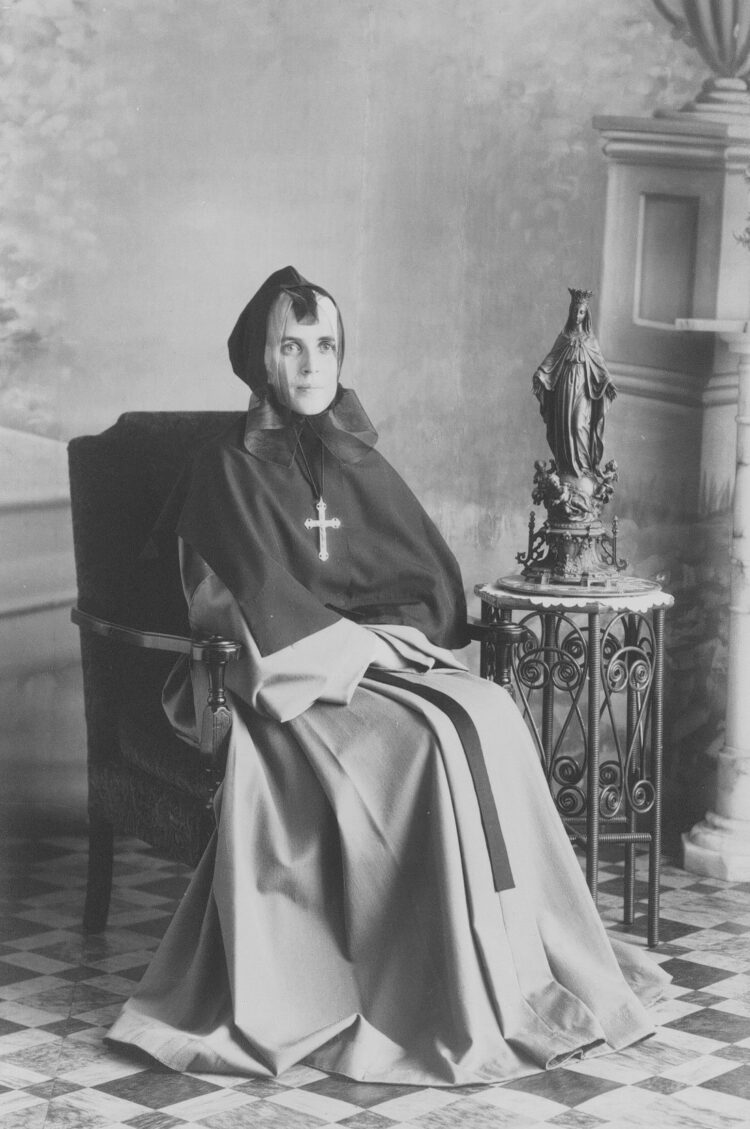

New shot of Marie-Alice Dumont. This time she is shown from the side and slightly from the back. She is accompanied by the interviewer. The two women are looking at Dumont’s photographs displayed in a room of the seniors’ residence where she lives. The retired photographer points to photos and seems to be explaining things to the interviewer.

We hear the interviewer and Marie-Alice Dumont continuing their discussion in voice-over. The first asks:

Were you the only woman photographer in the area?

Dumont answers:

Uh, I think so. I haven’t heard of another one who did photography of… yes…

The interviewer tries to complete:

In this region here…

Dumont resumes the thread of her thought:

… classic [photography] like that, yes.

The interviewer resumes:

But didn’t people find it a little weird to be photographed by a woman?

Dumont answers:

They didn’t talk about it. Haha!

The interviewer elaborates:

They took advantage of it!

Dumont answers:

Uh, yes. Haha!

The interviewer resumes:

And if you had to start over, if your life were to start over, would you do the same job?

Dumont answers:

Oh, I would do the same thing, I would do the same thing because I couldn’t do anything else. Haha!

The interviewer asks Dumont a final question:

But did you enjoy it?

Dumont answers:

Did I enjoy it? Well yes, I enjoyed it!

17 :45 – 19 :34

The credits are presented. The following information and message are provided, interspersed with images from the interview.

Original idea: Alain Ross

Research: Christine Dionne

Interviewer: Céline De Guise

Camera: Yvan Roy

Editing: Yvan Roy, Andrée Dionne

Directed by: Yvan Roy, Andrée Dionne

Collaboration: Musée du Bas-St-Laurent, Cégep de Rivière-du-Loup, T.V.C.K. St-Pascal

A special thank you to Marie-Alice for her wonderful participation.