d1553

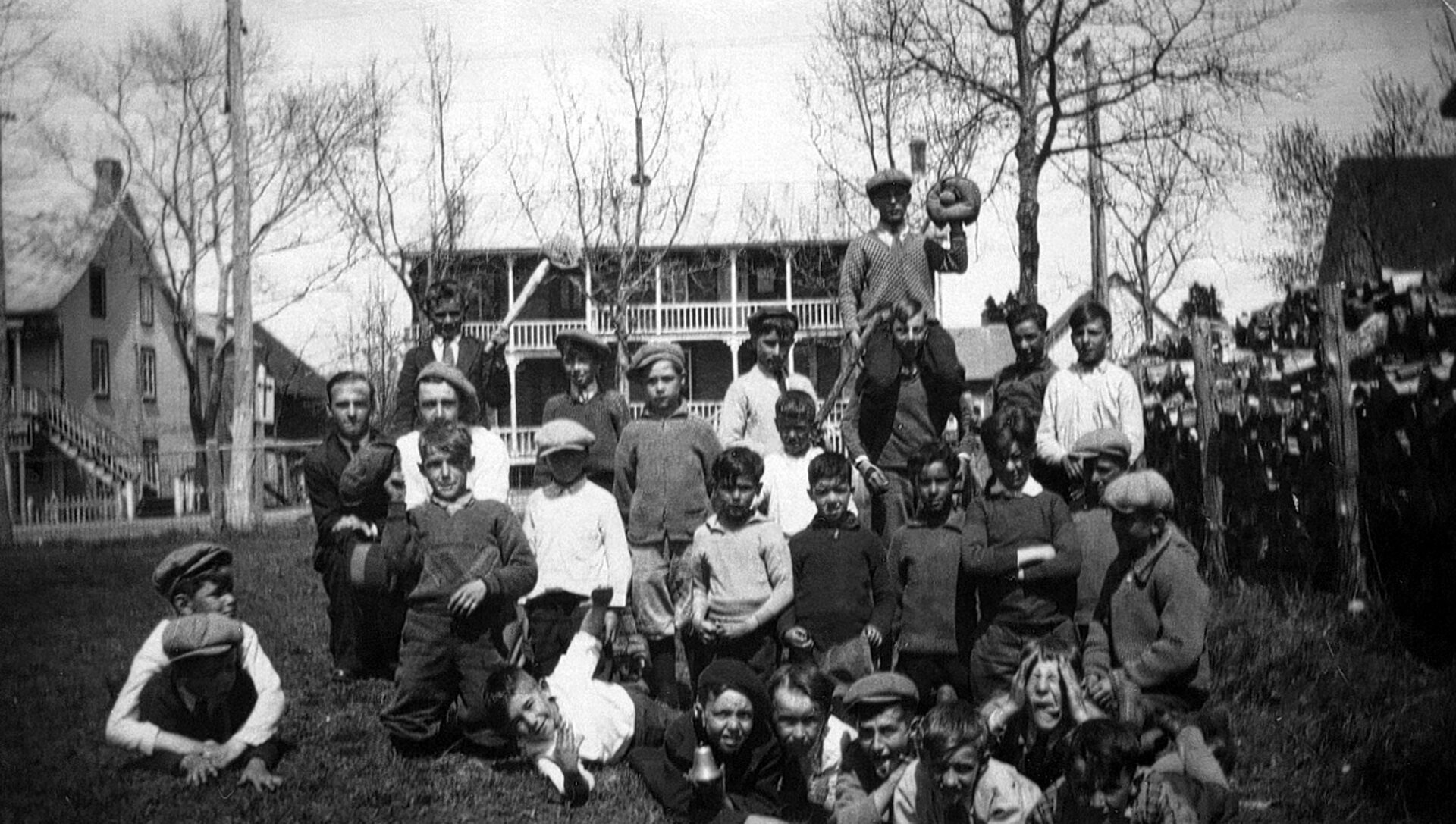

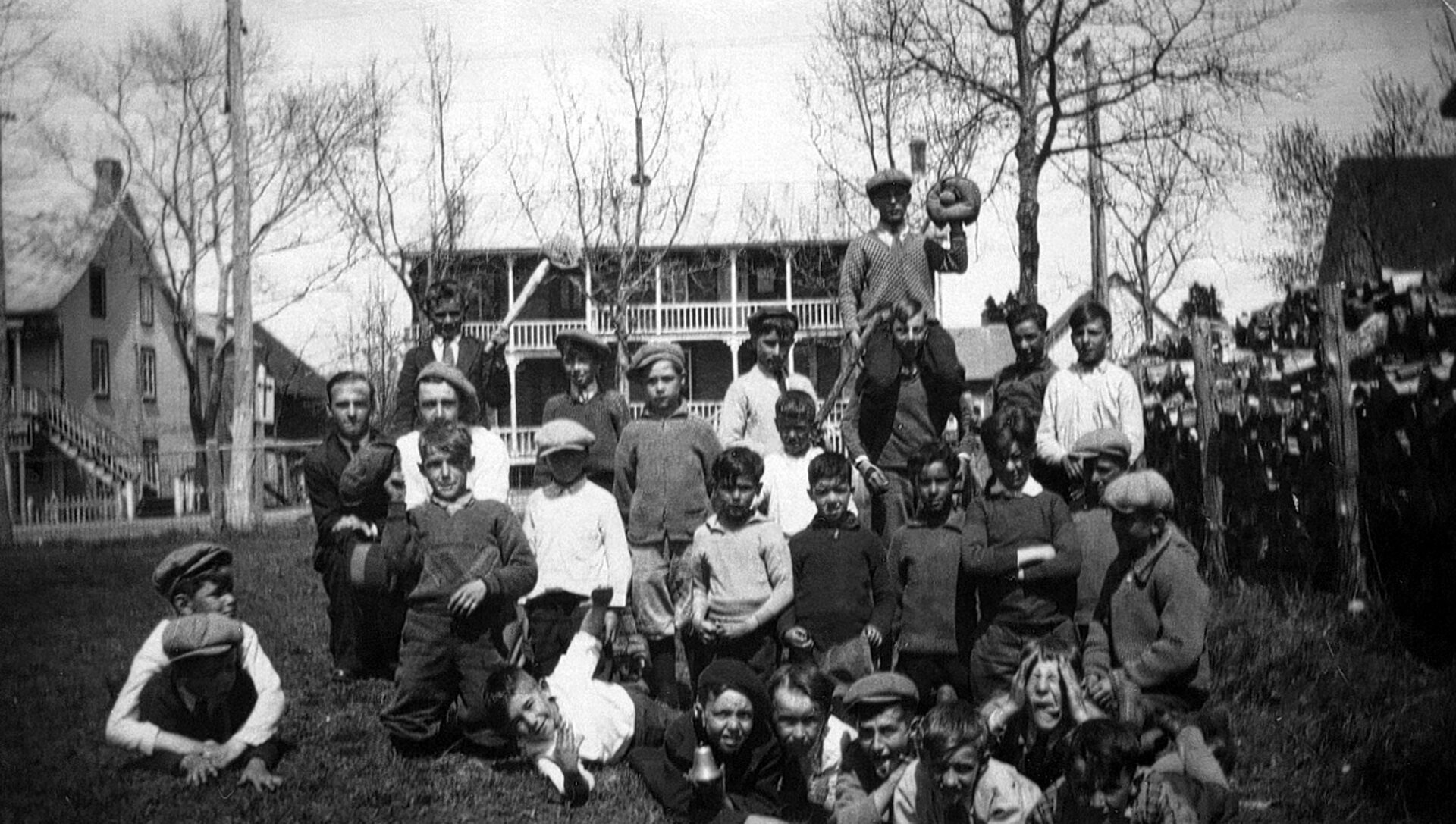

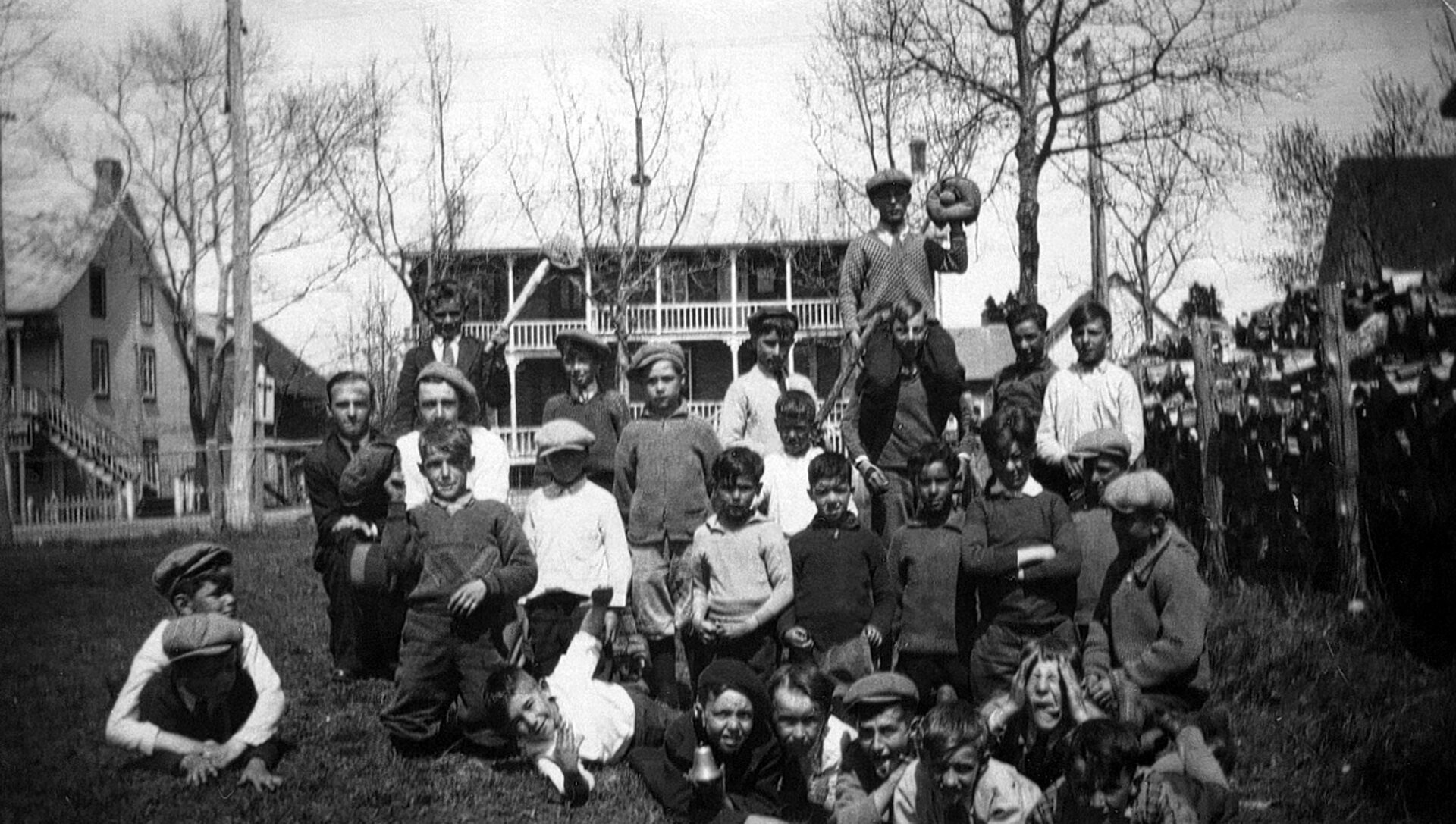

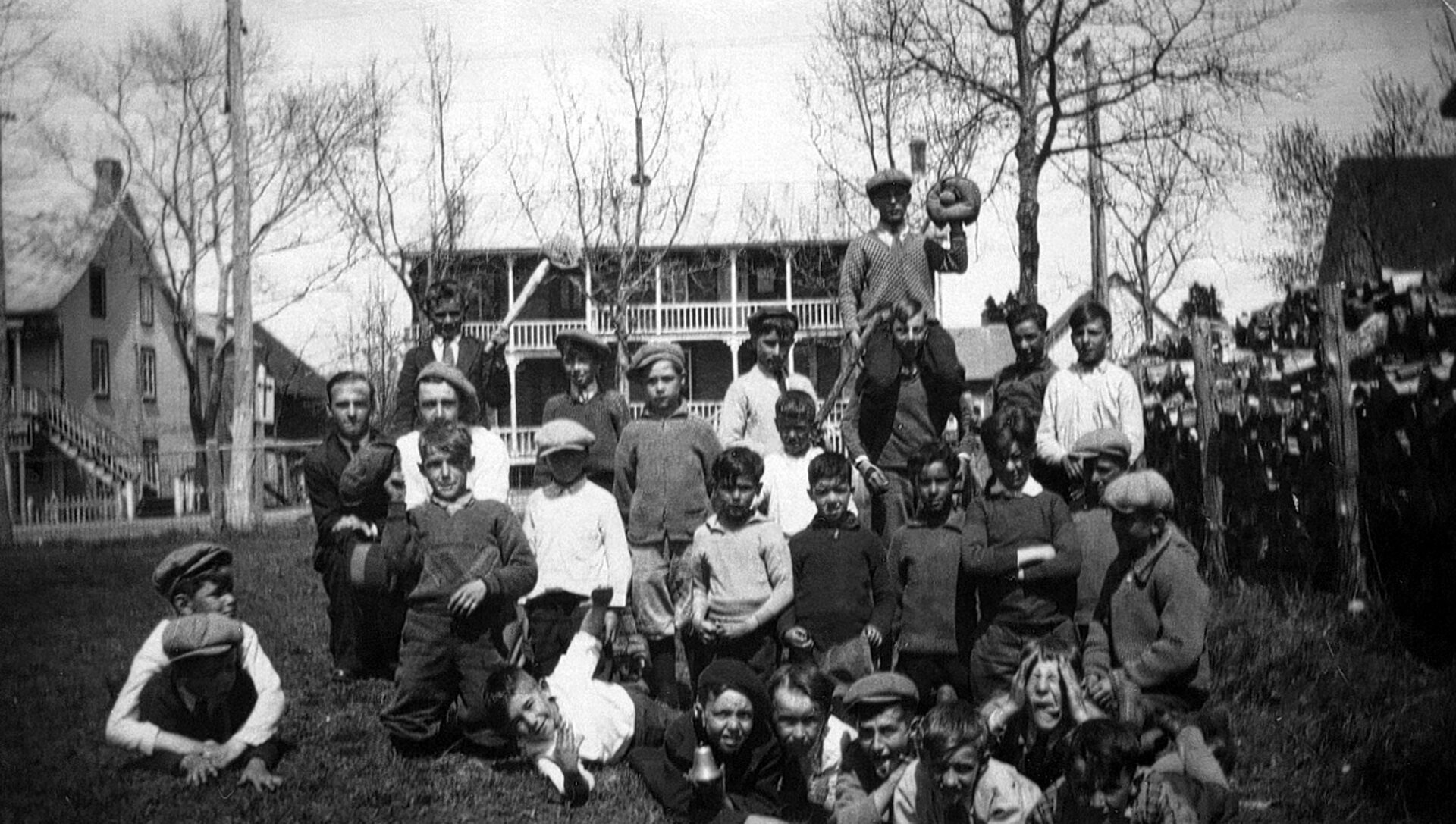

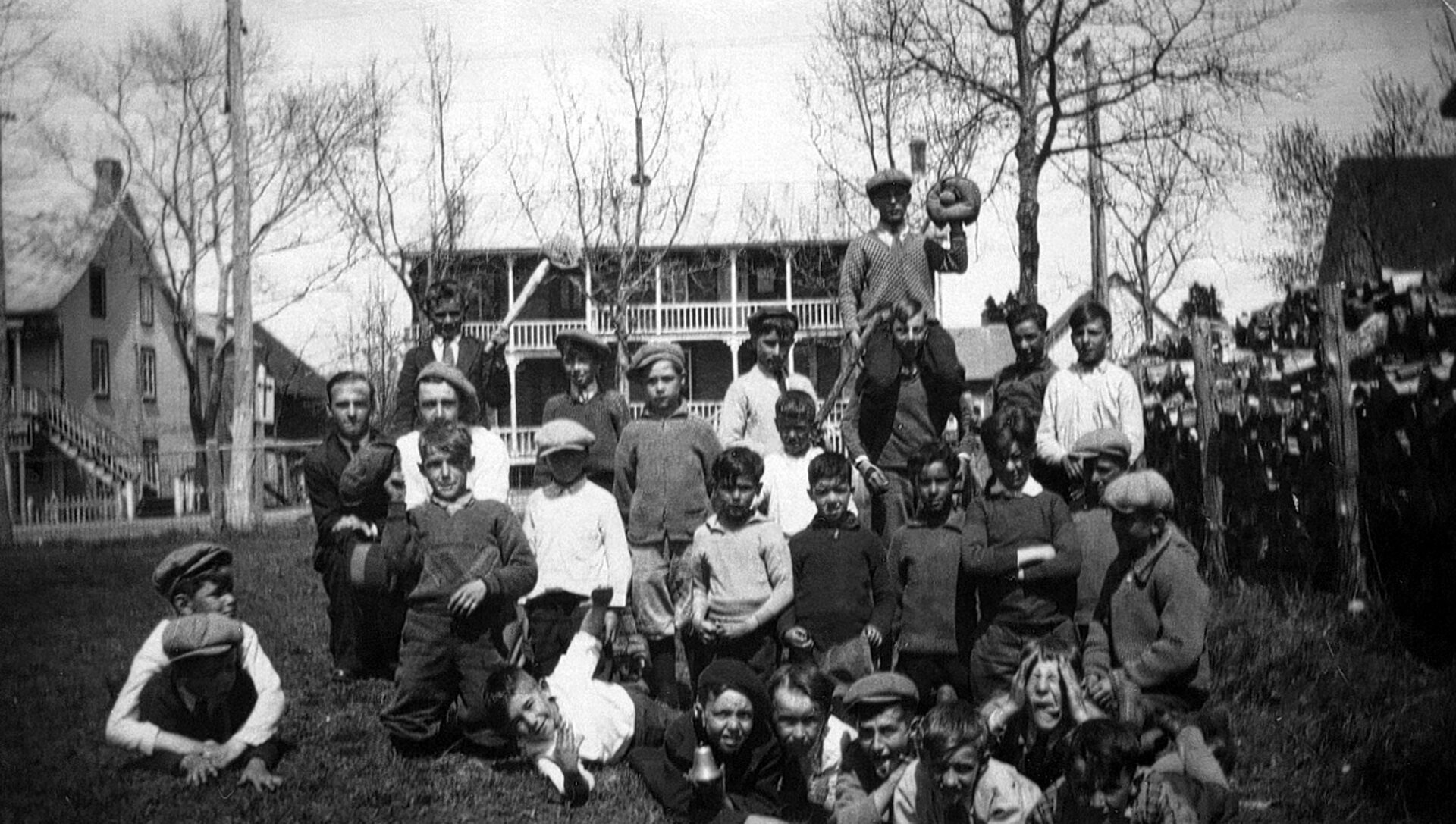

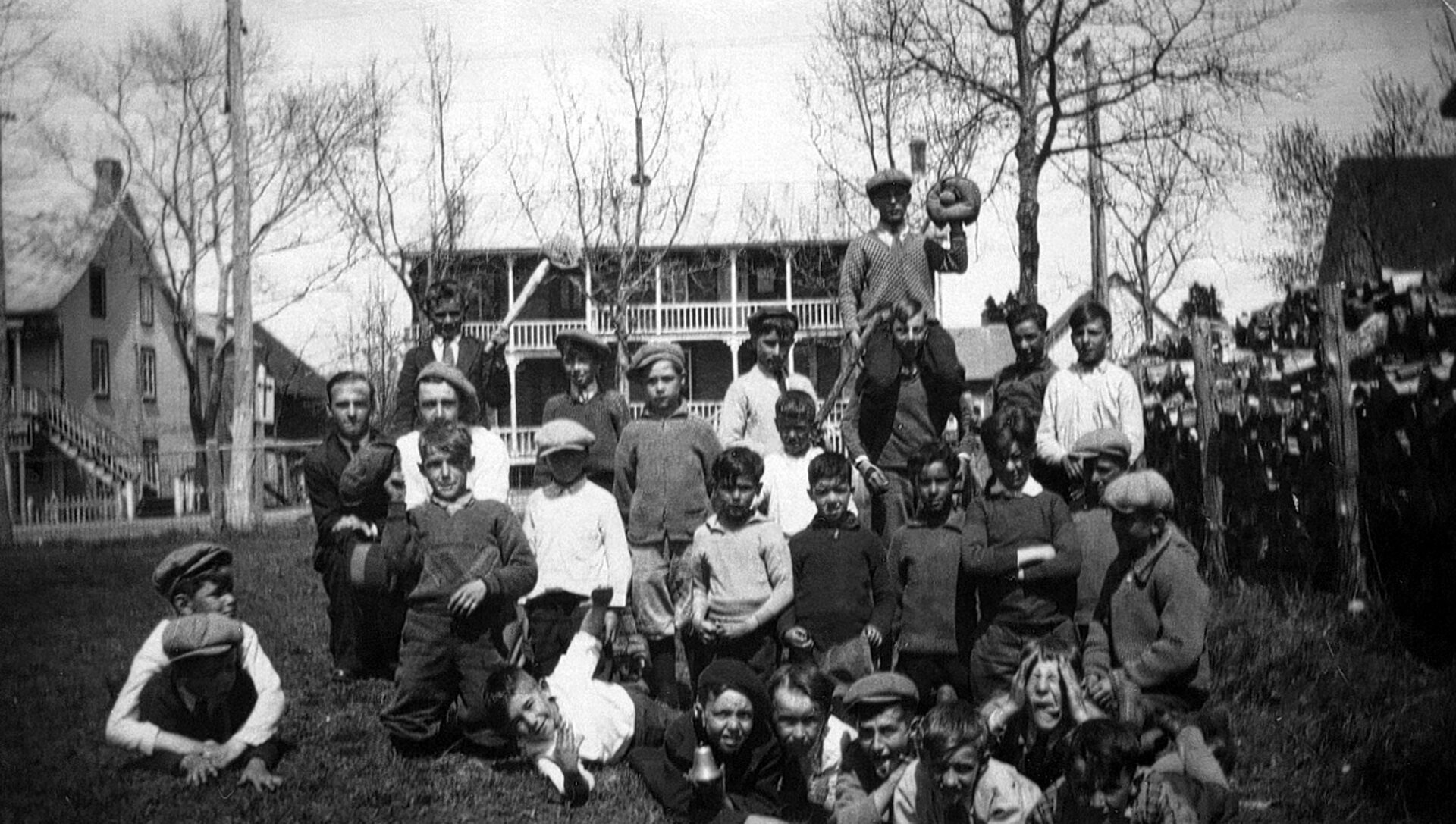

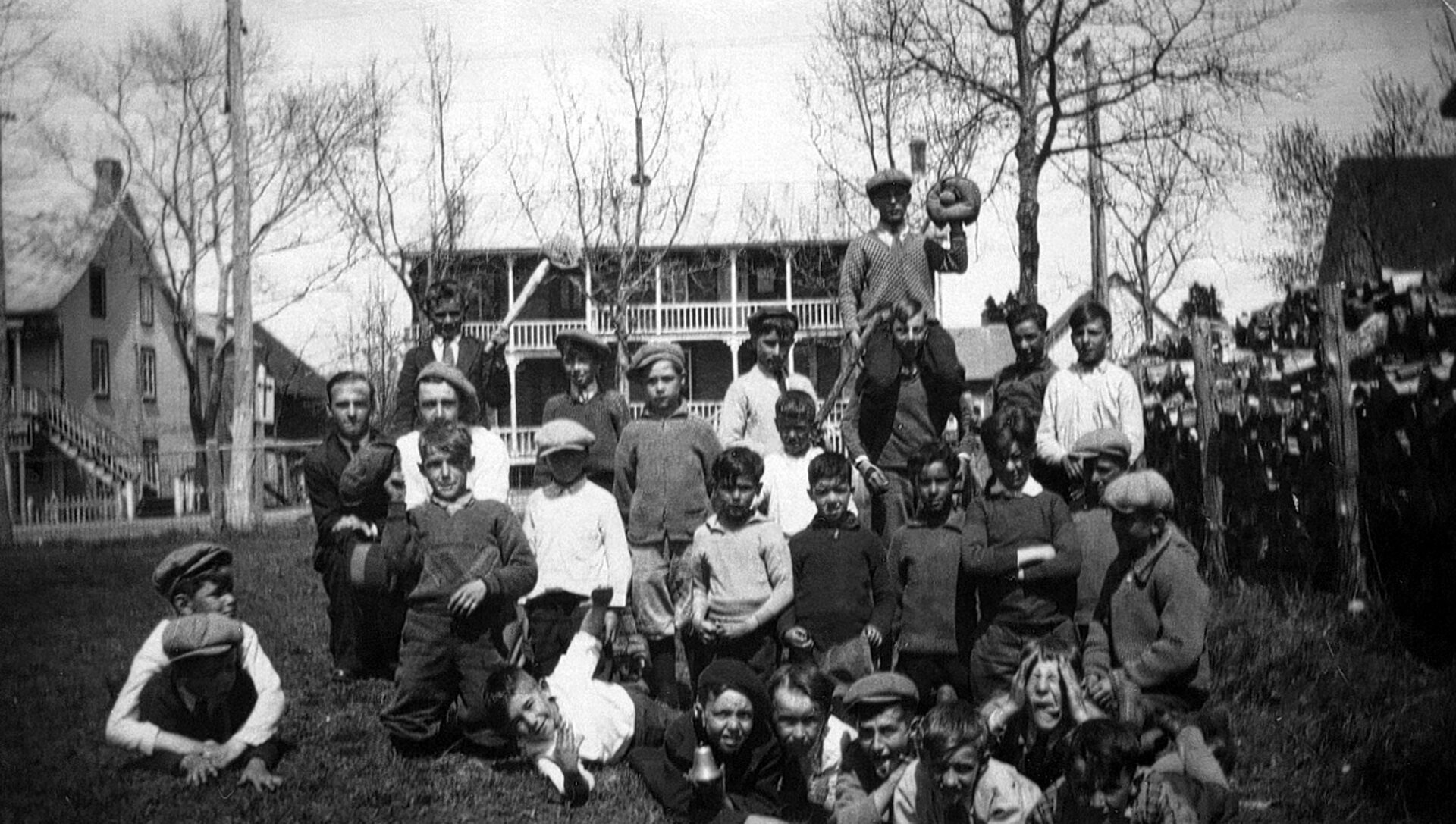

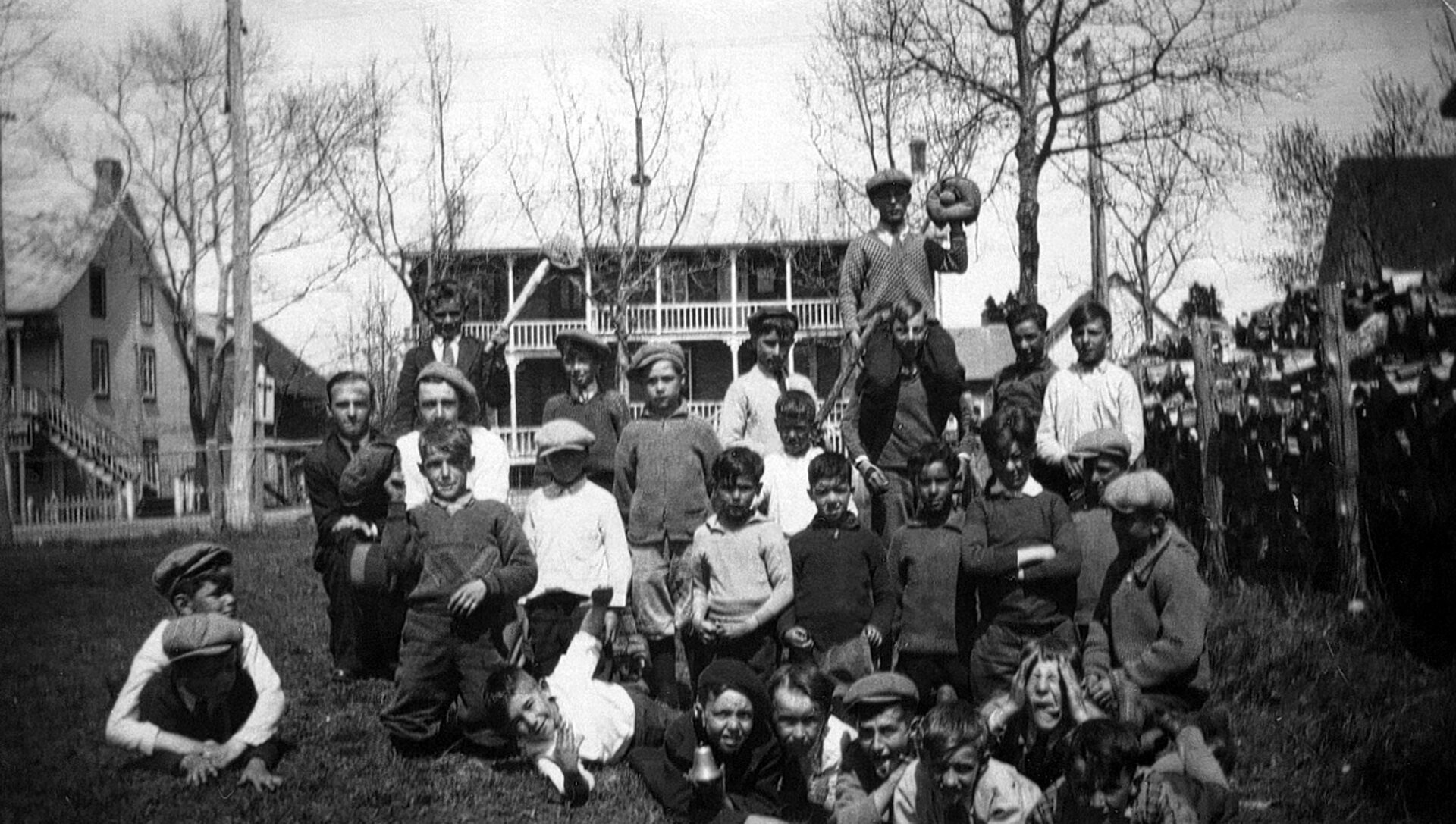

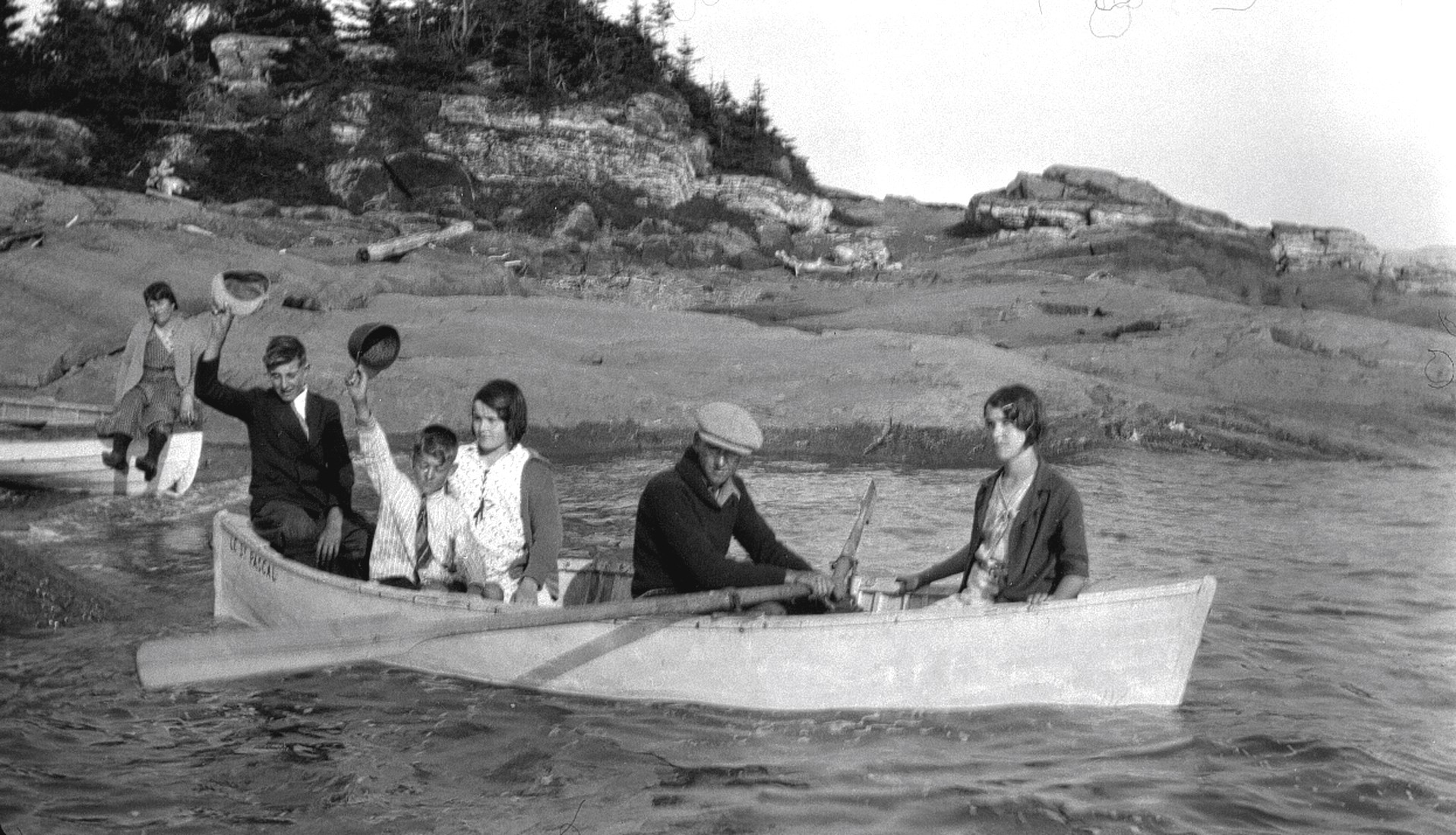

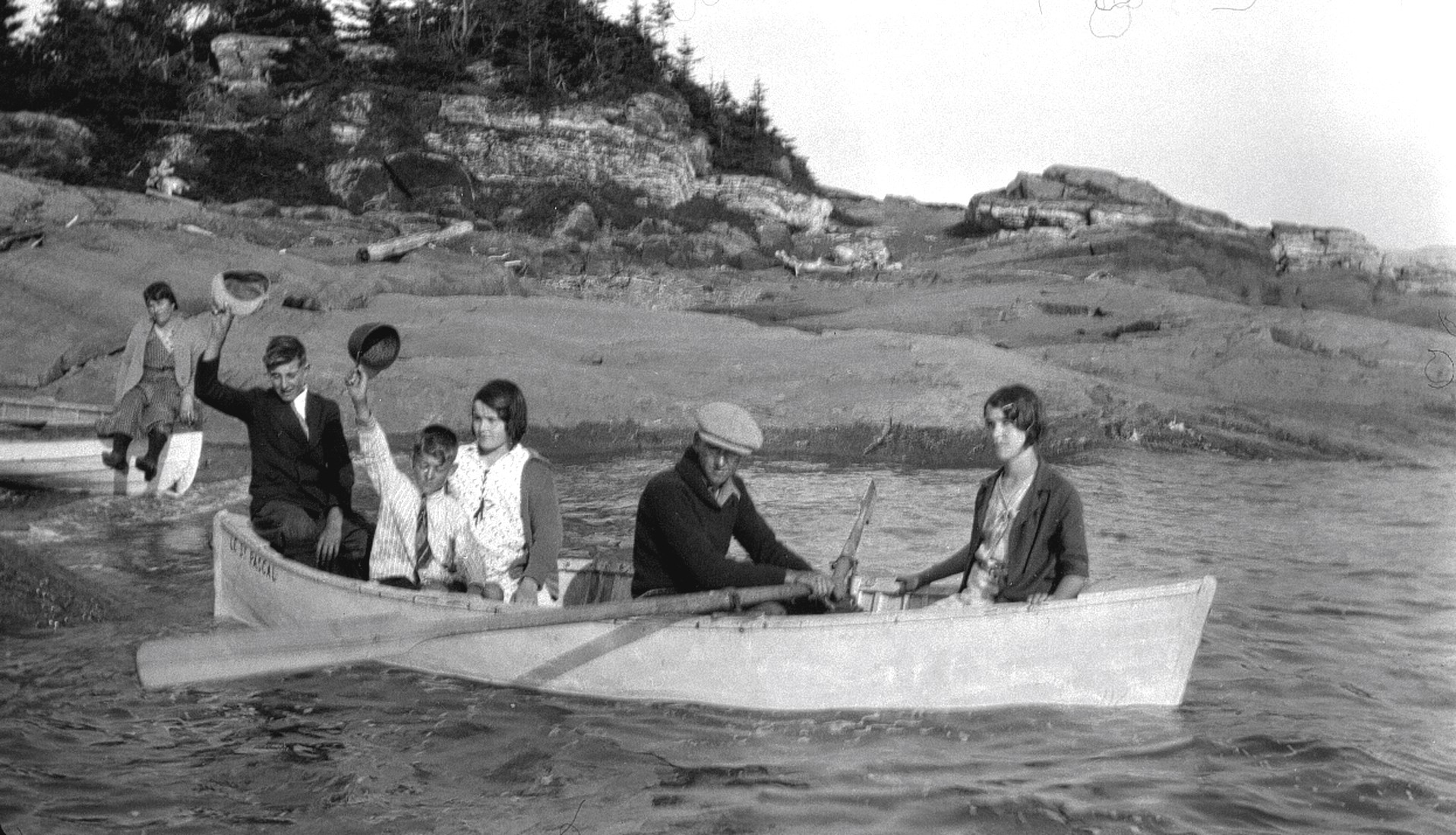

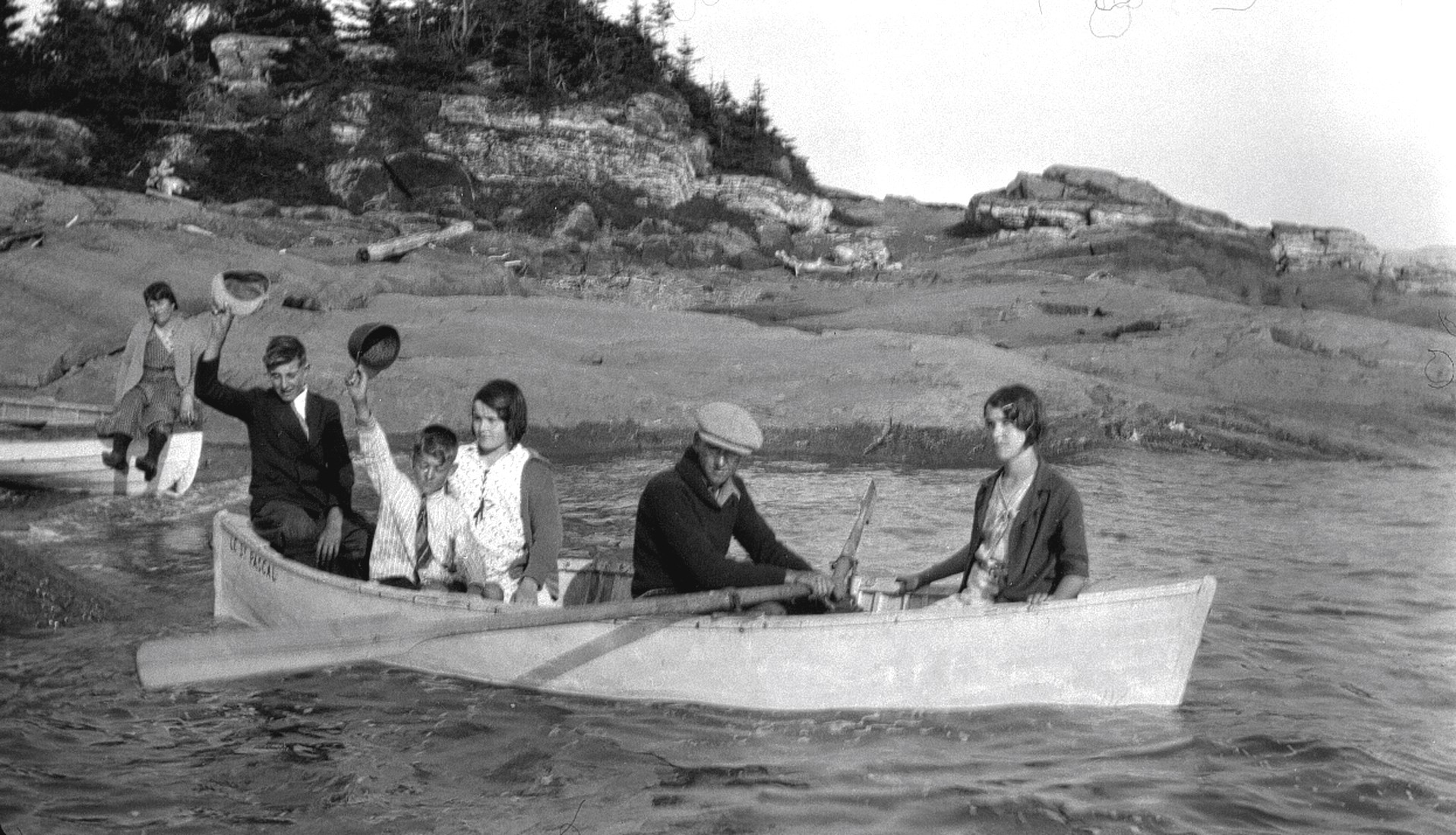

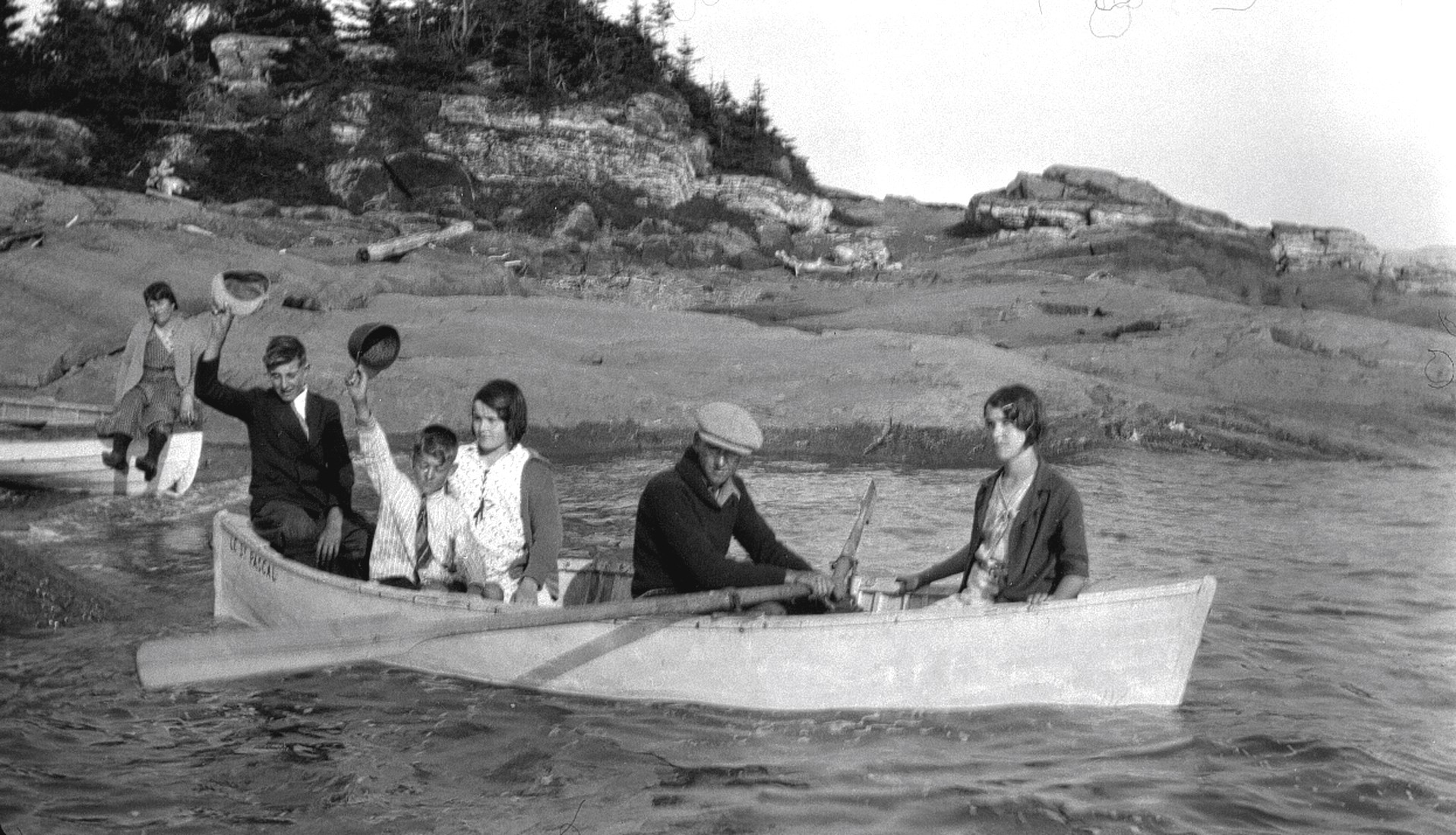

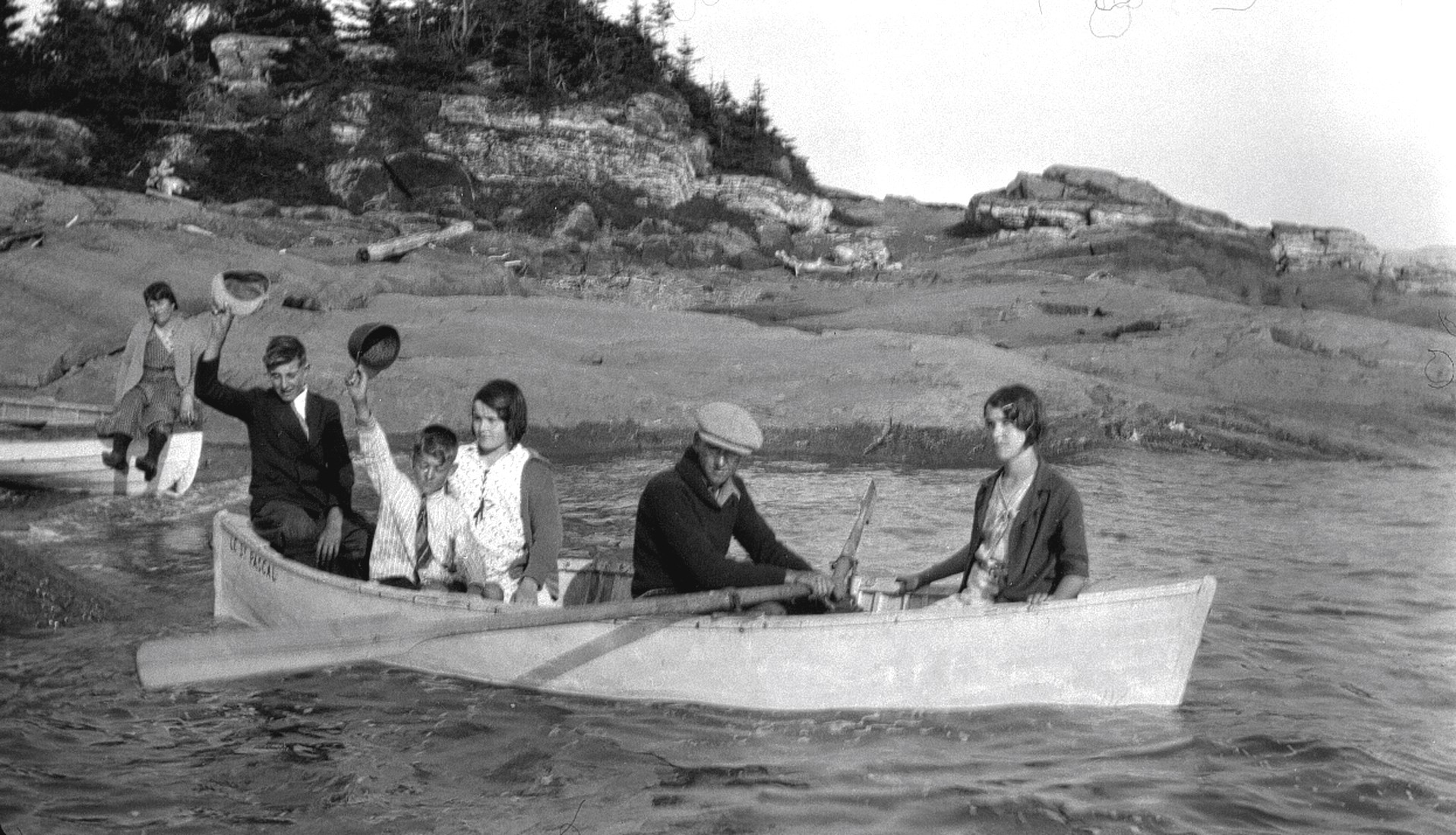

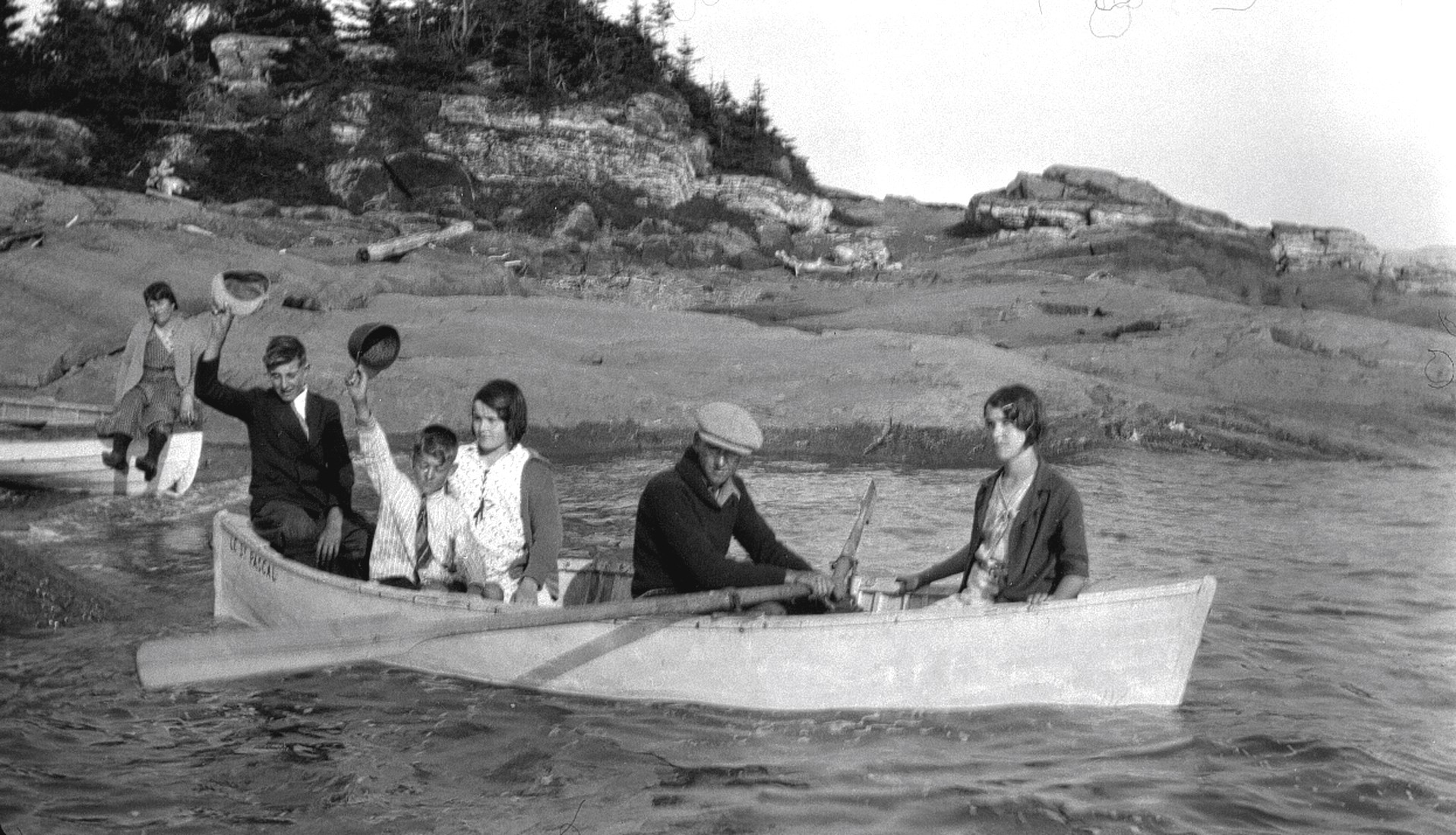

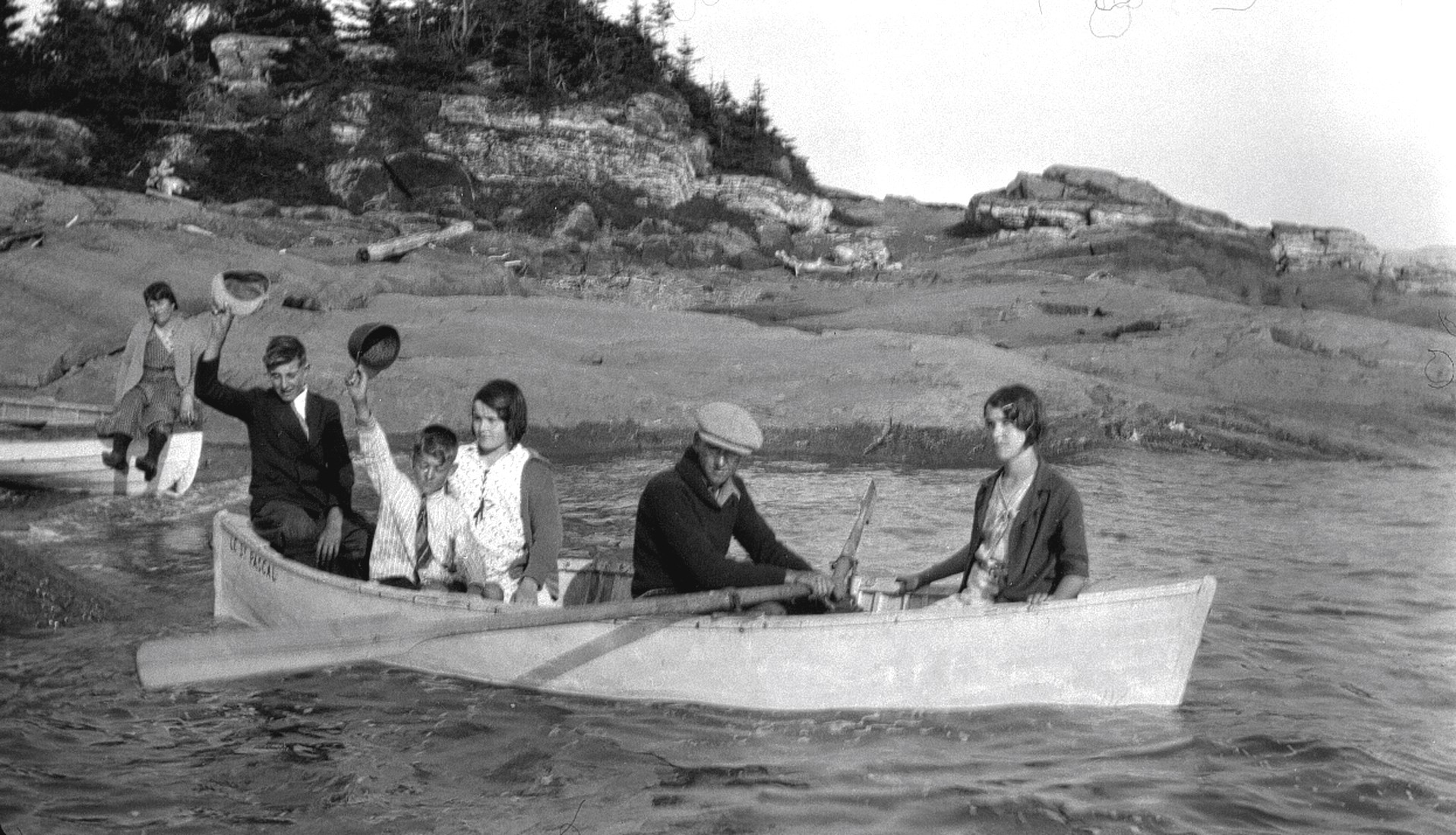

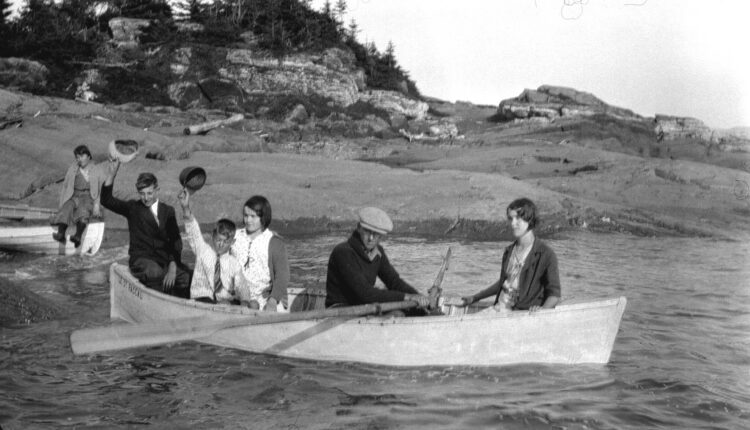

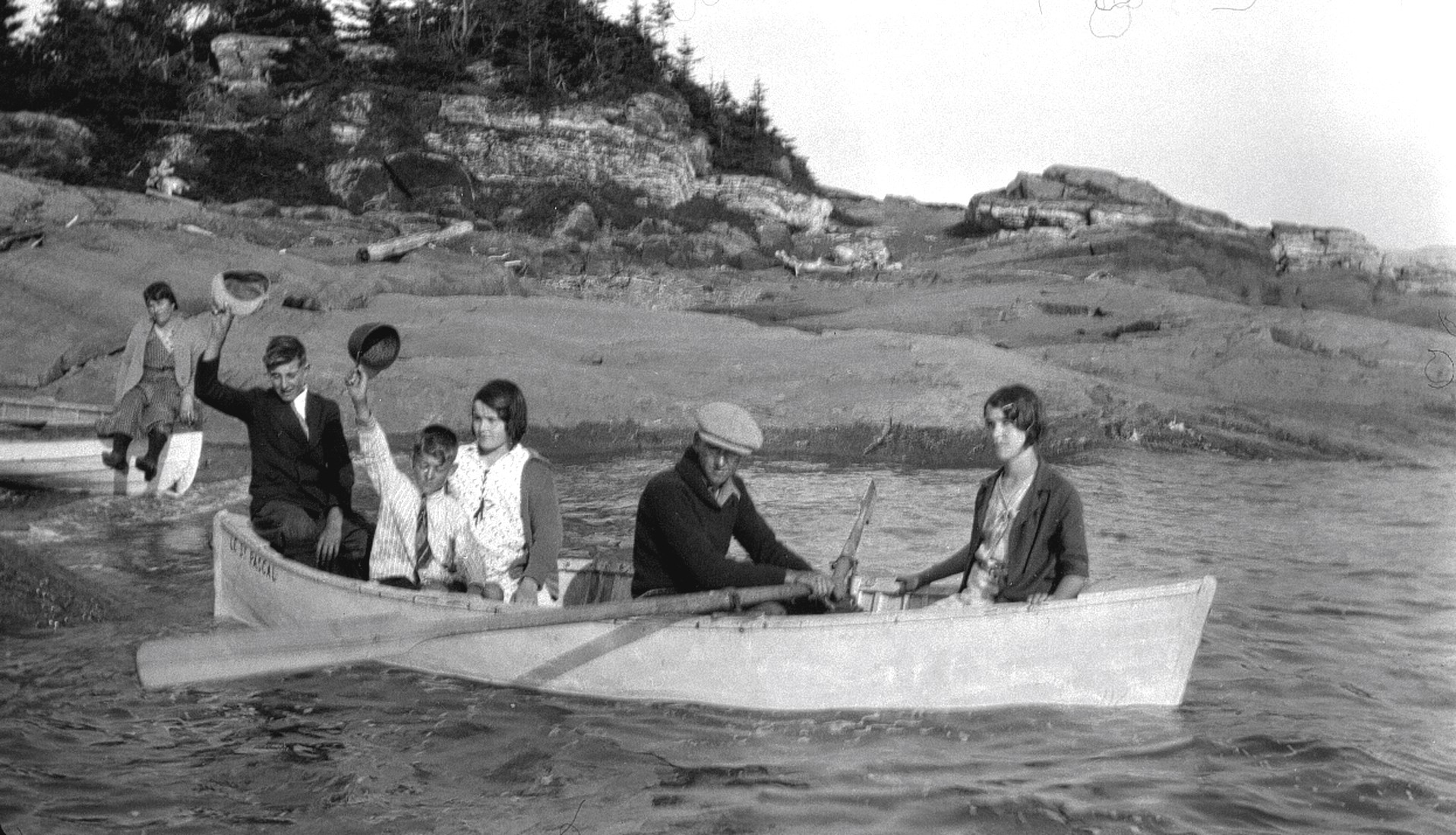

1925Photographe: Photographer: Marie-Alice DumontOne of the Dumont family’s favourite pastimes was visiting relatives on the weekends. In this photo, Marie-Alice Dumont captures one of those cherished moments between cousins.

One of the Dumont family’s favourite pastimes was visiting relatives on the weekends. In this photo, Marie-Alice Dumont captures one of those cherished moments between cousins.

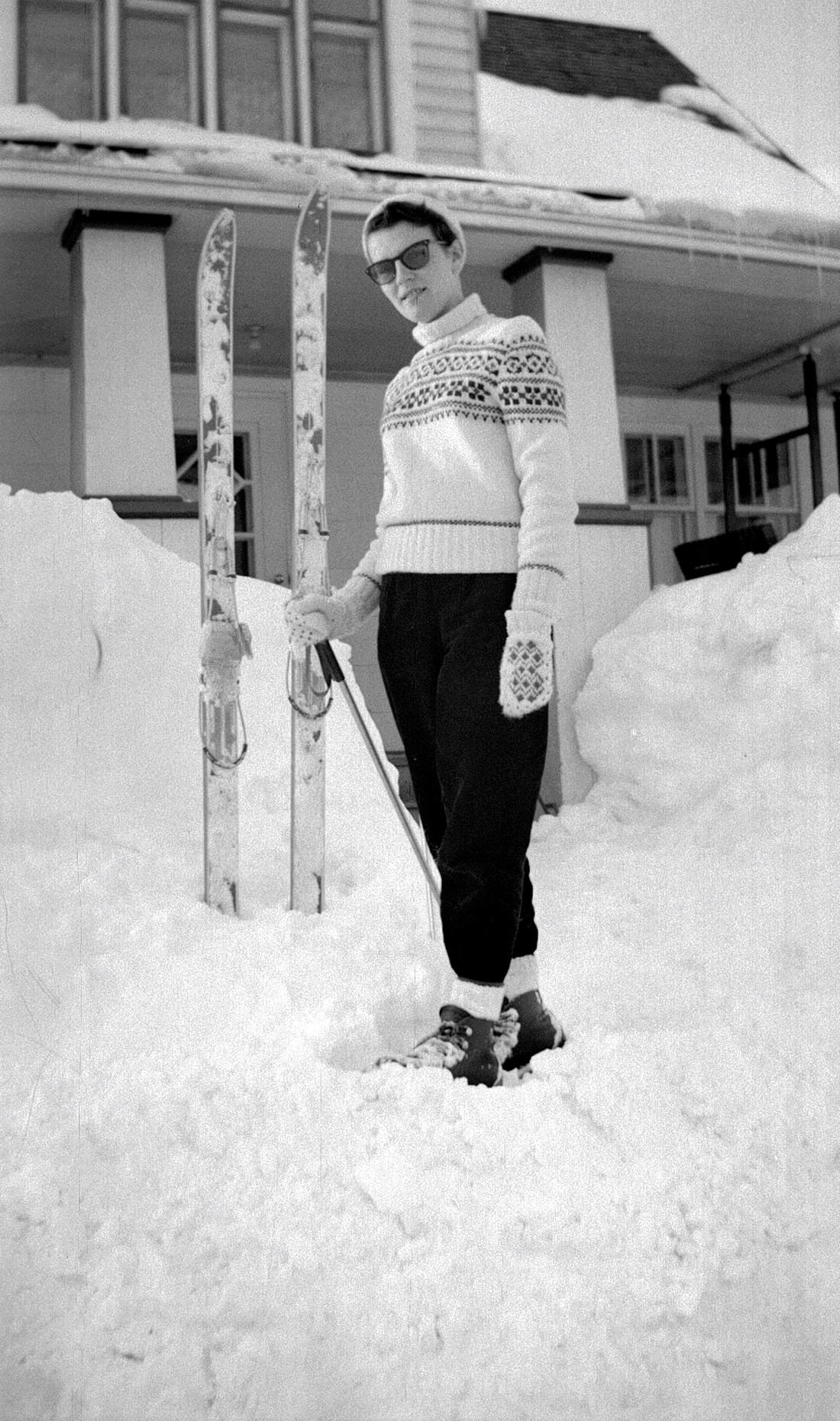

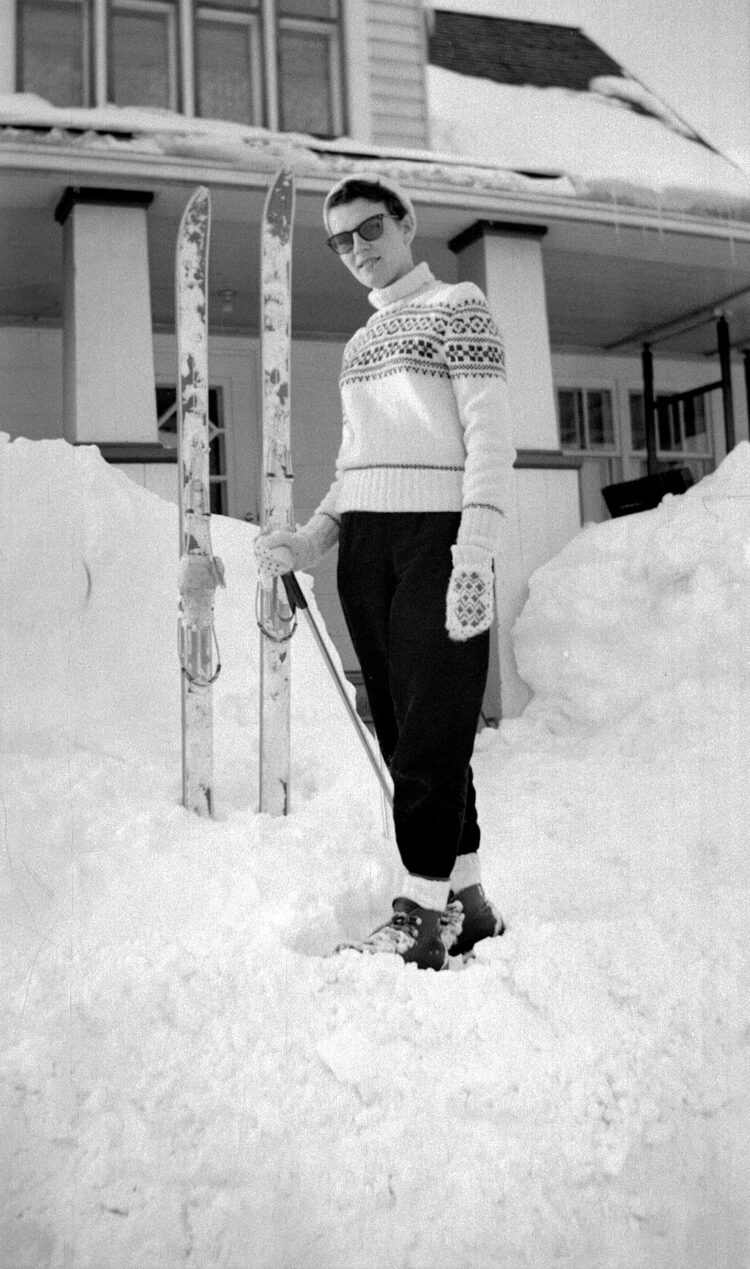

Skiing has been practised in Quebec since the late 19th century. By the time this photo was taken, in the 1920s, the sport was rapidly gaining popularity across the province, and the Bas-Saint-Laurent region was no exception.

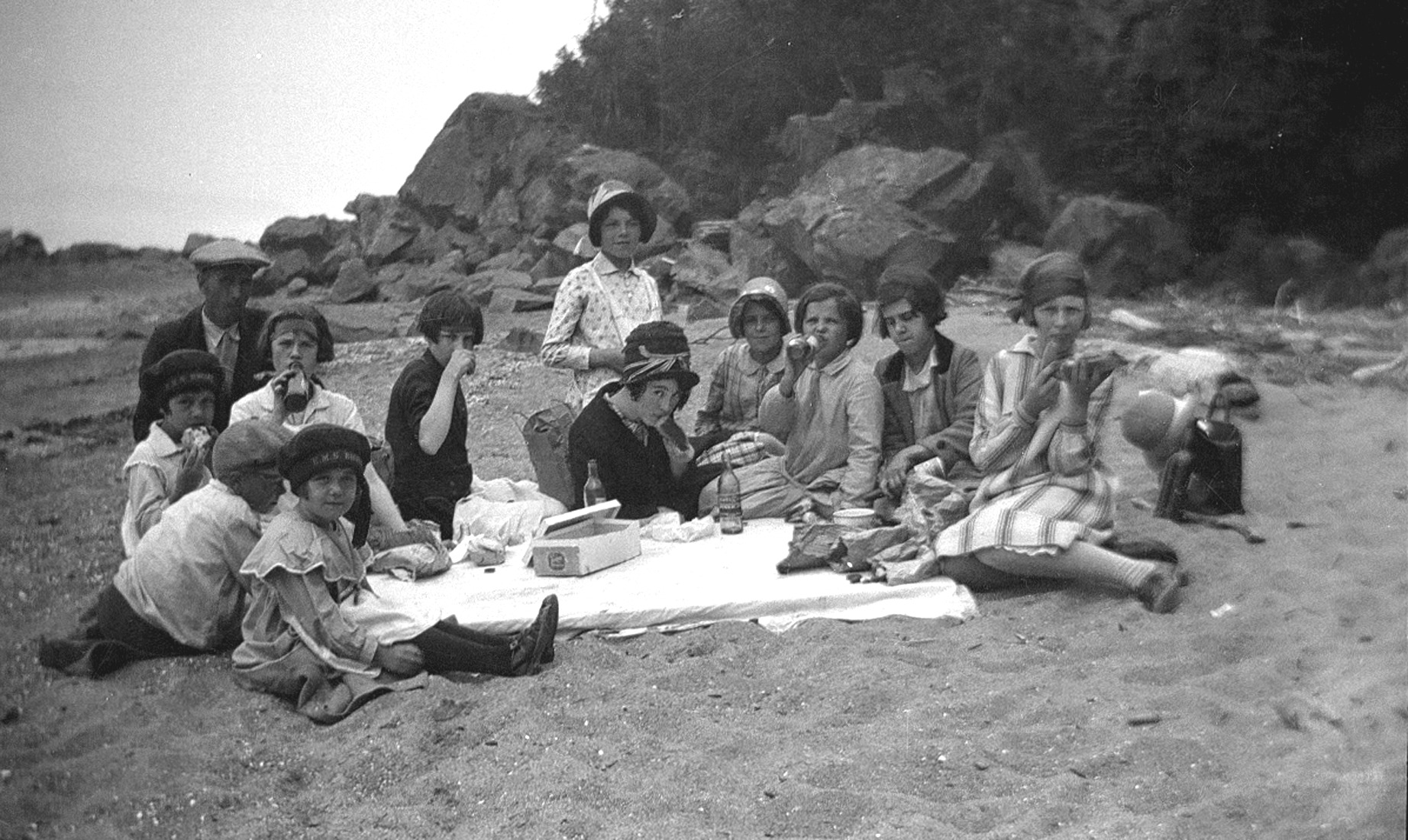

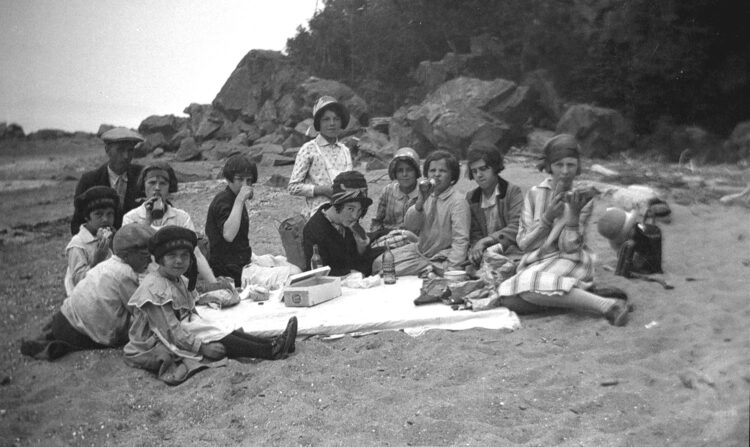

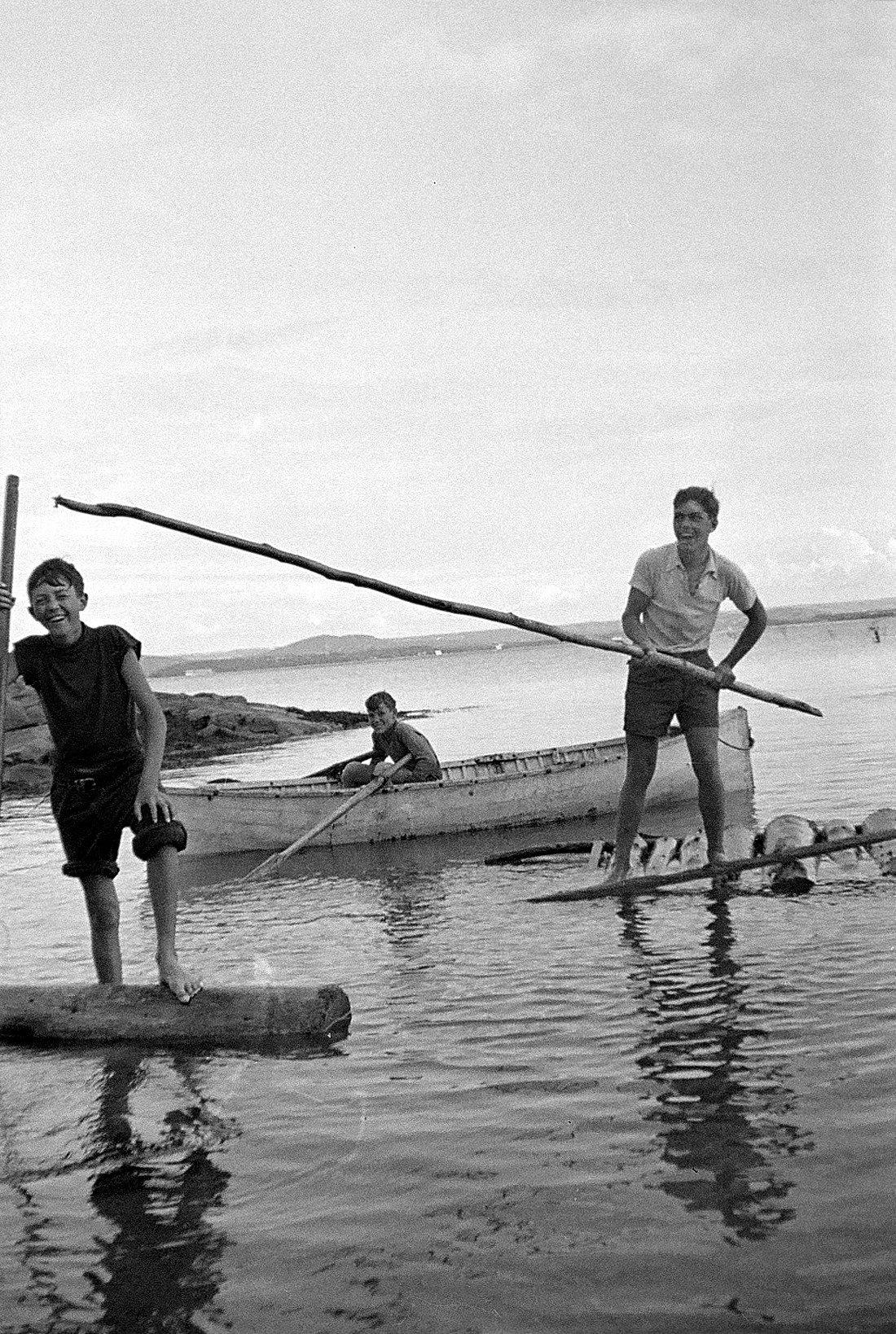

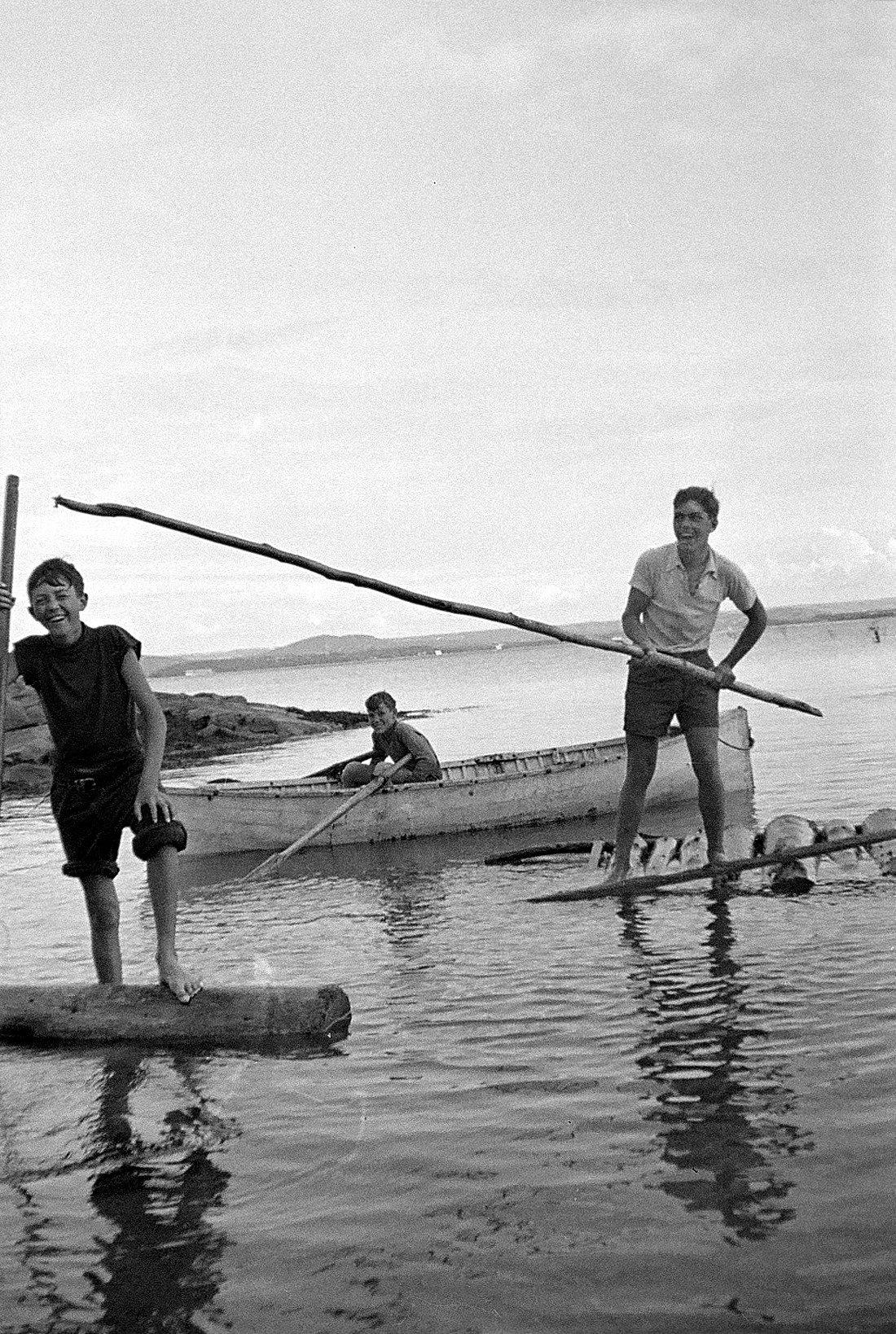

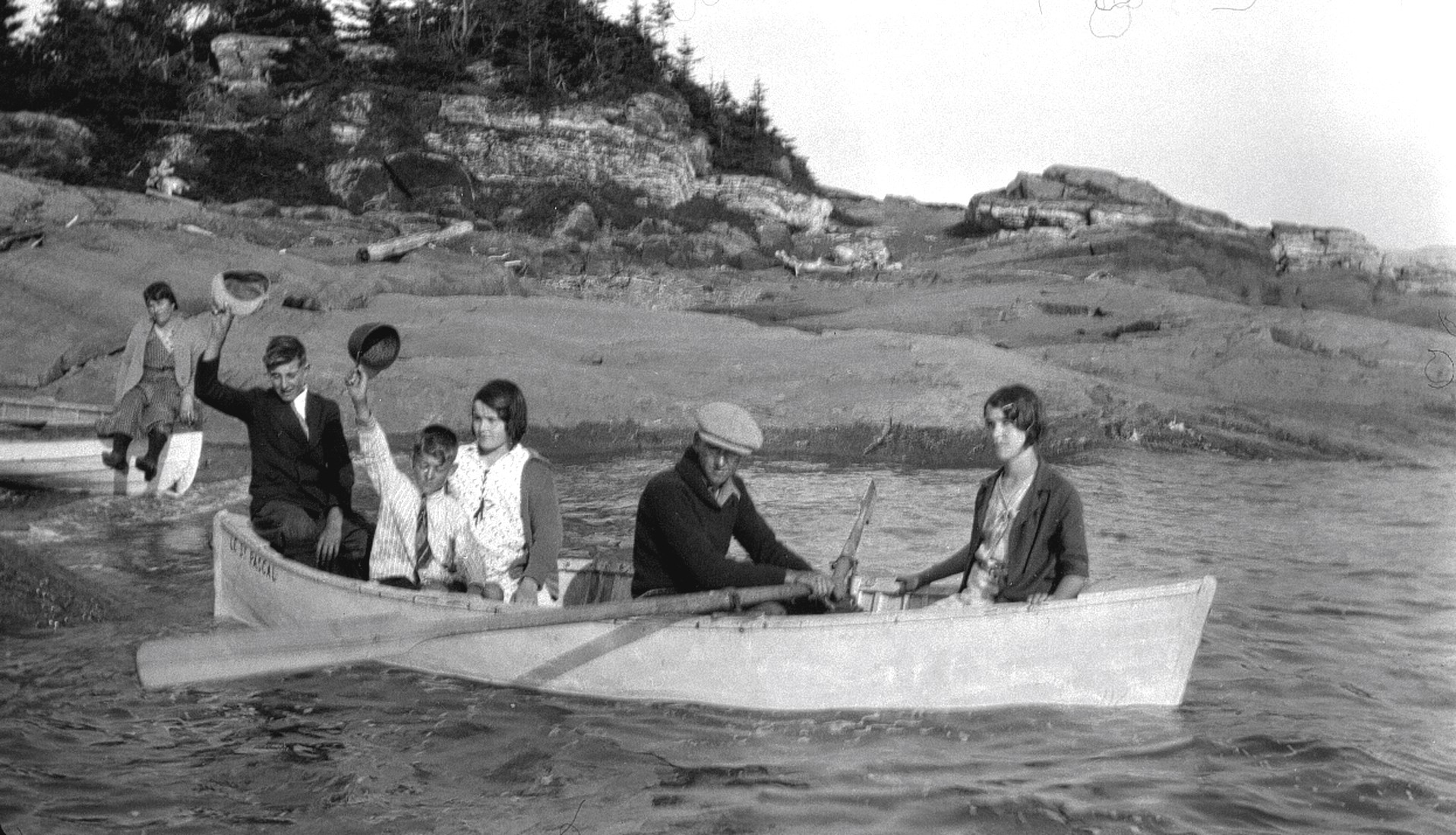

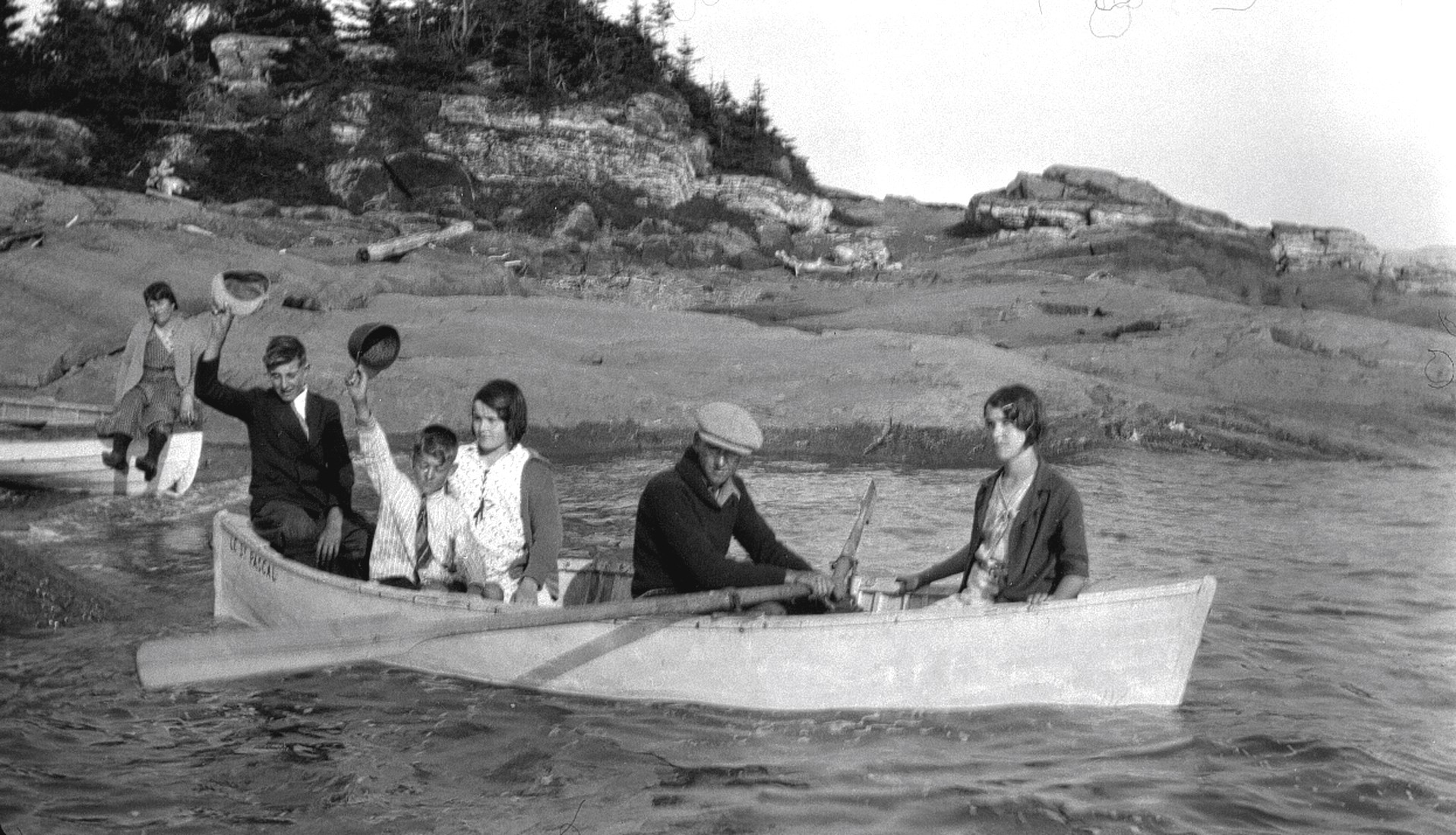

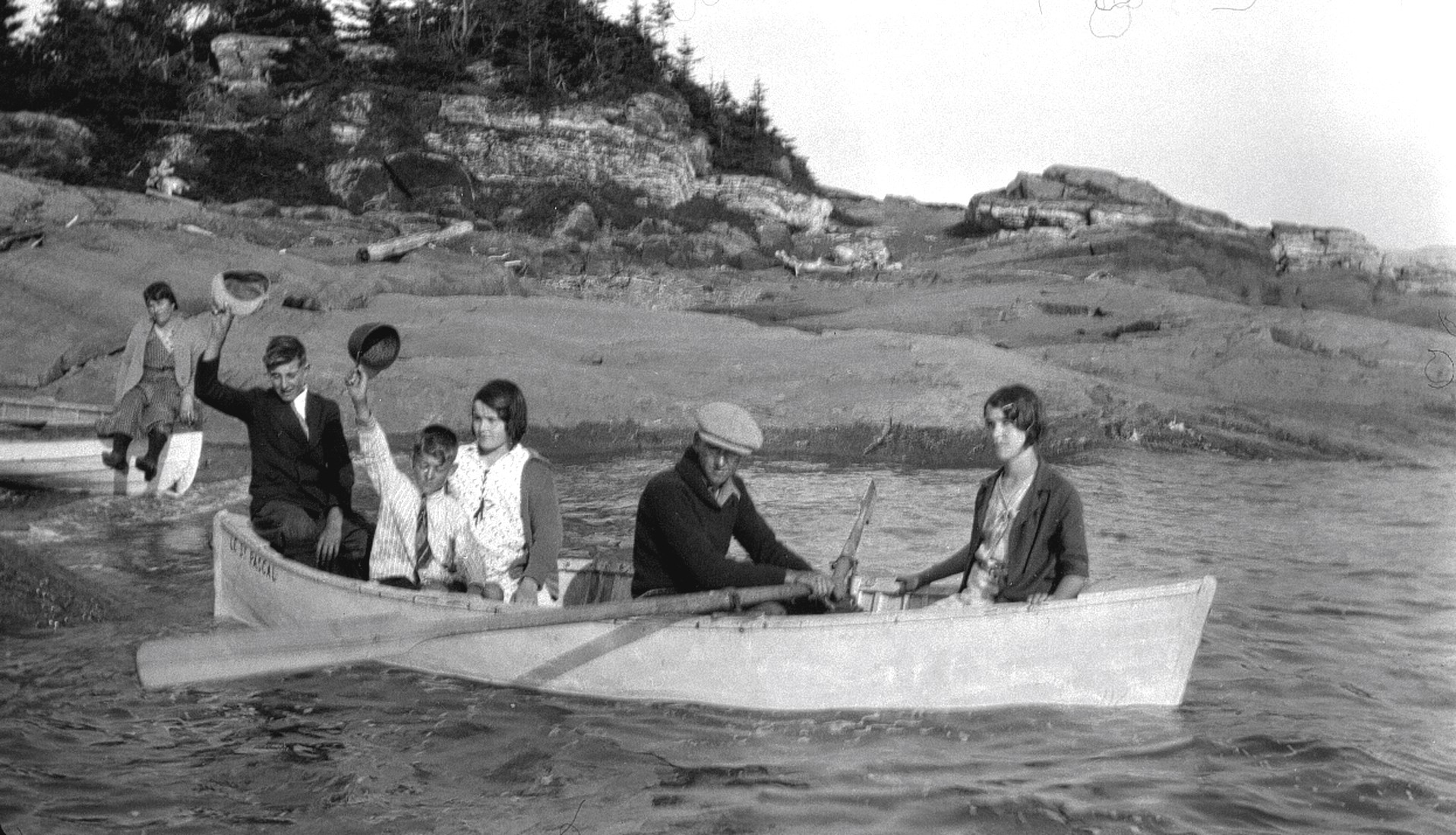

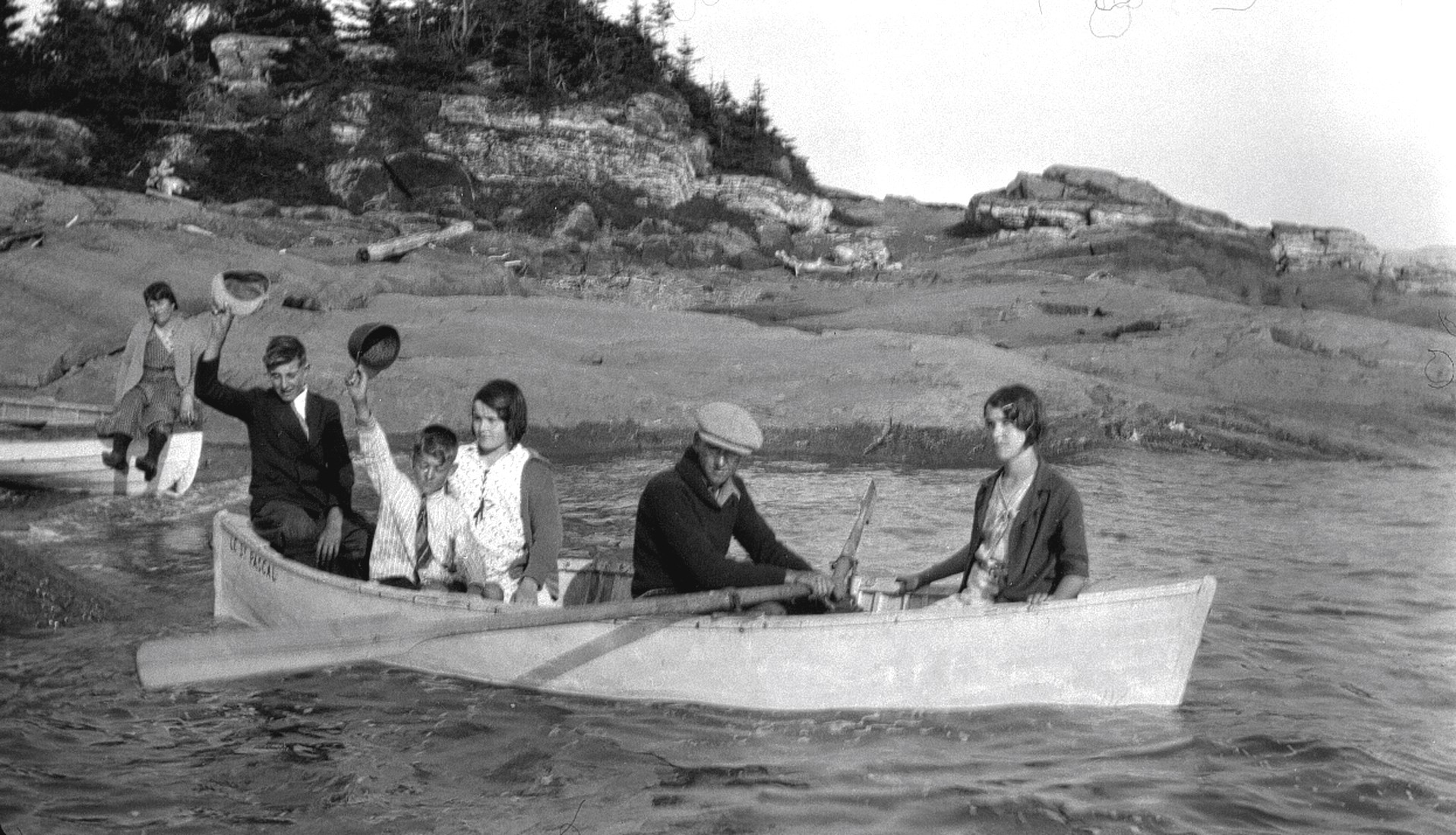

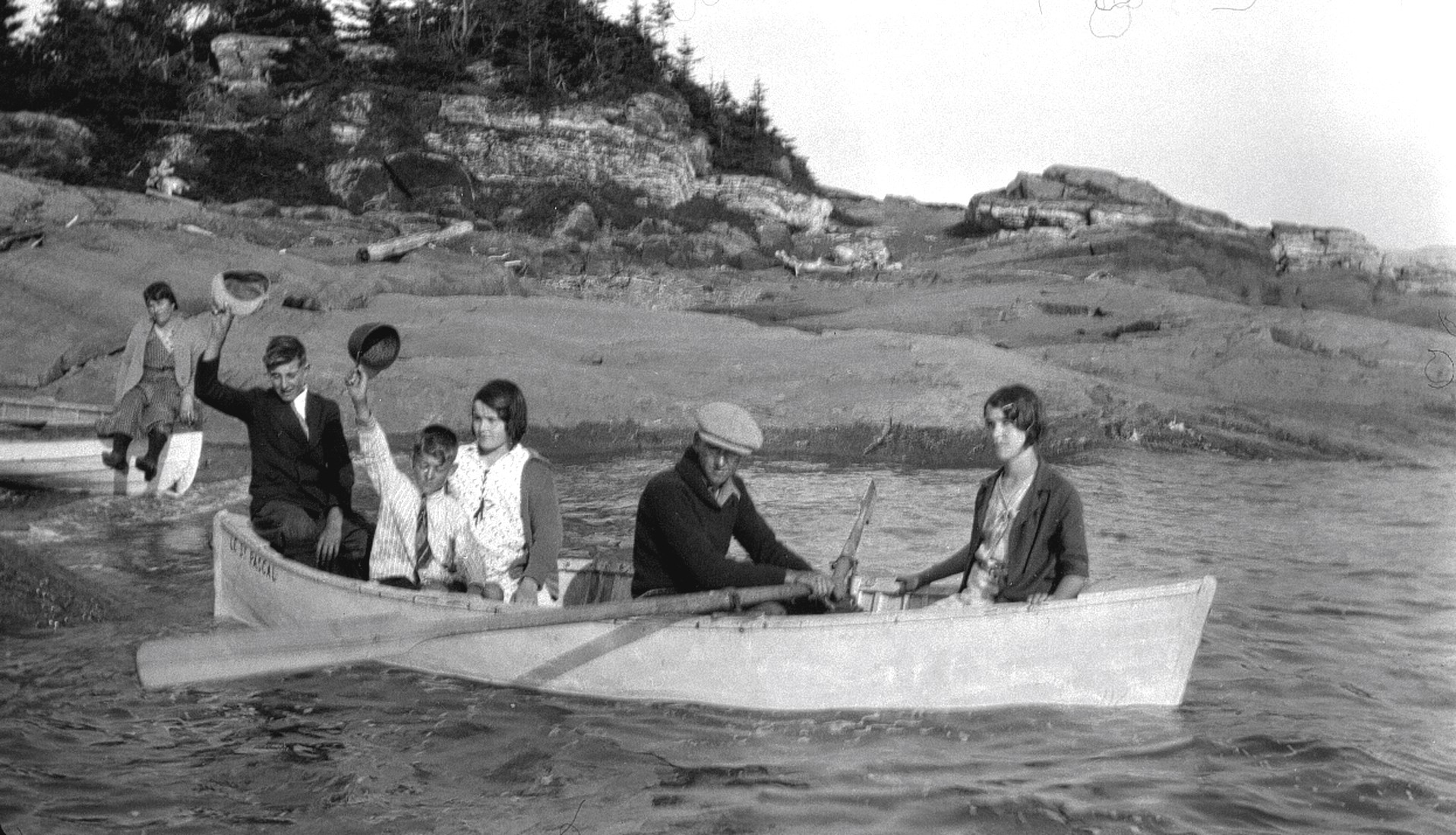

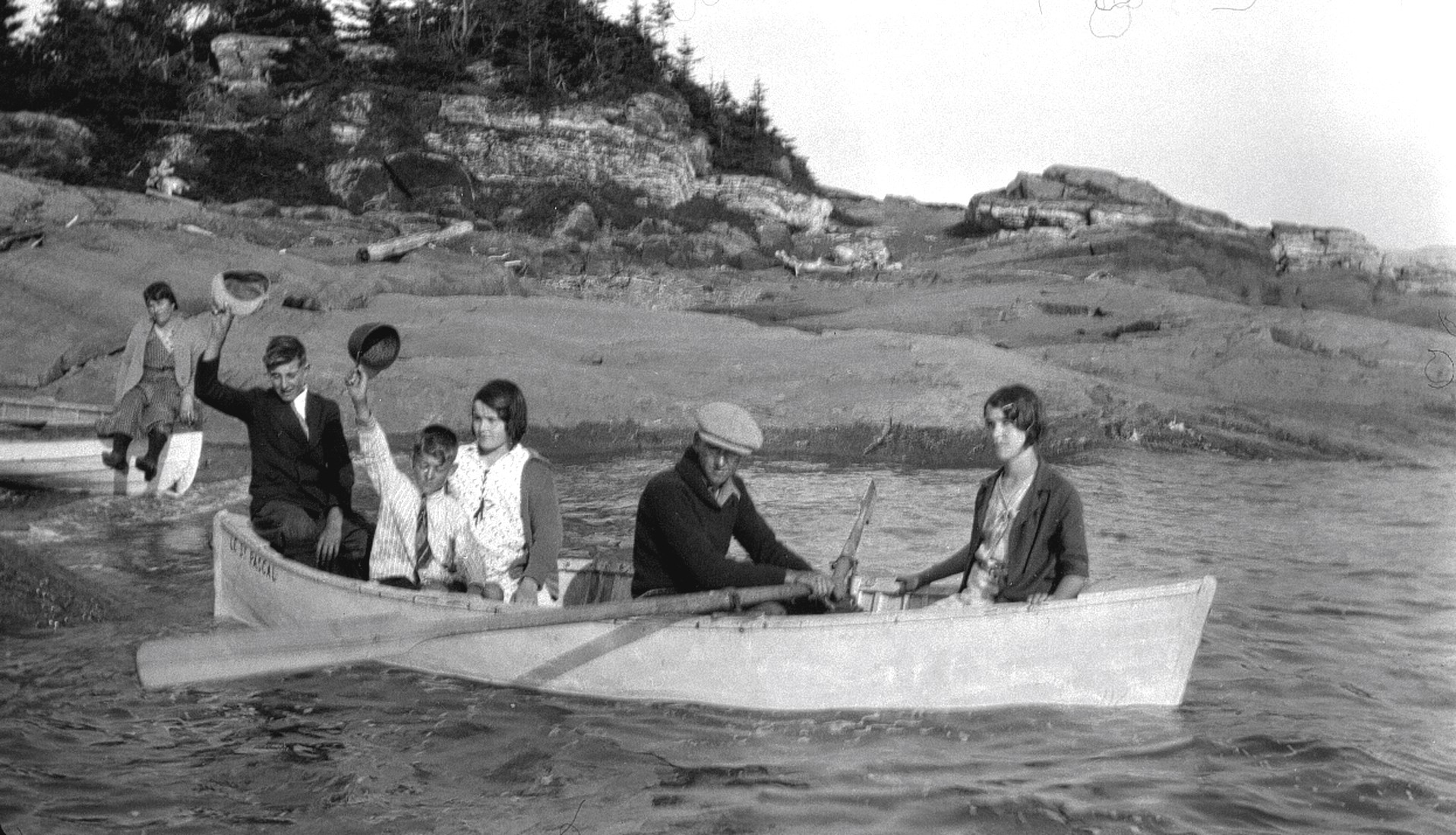

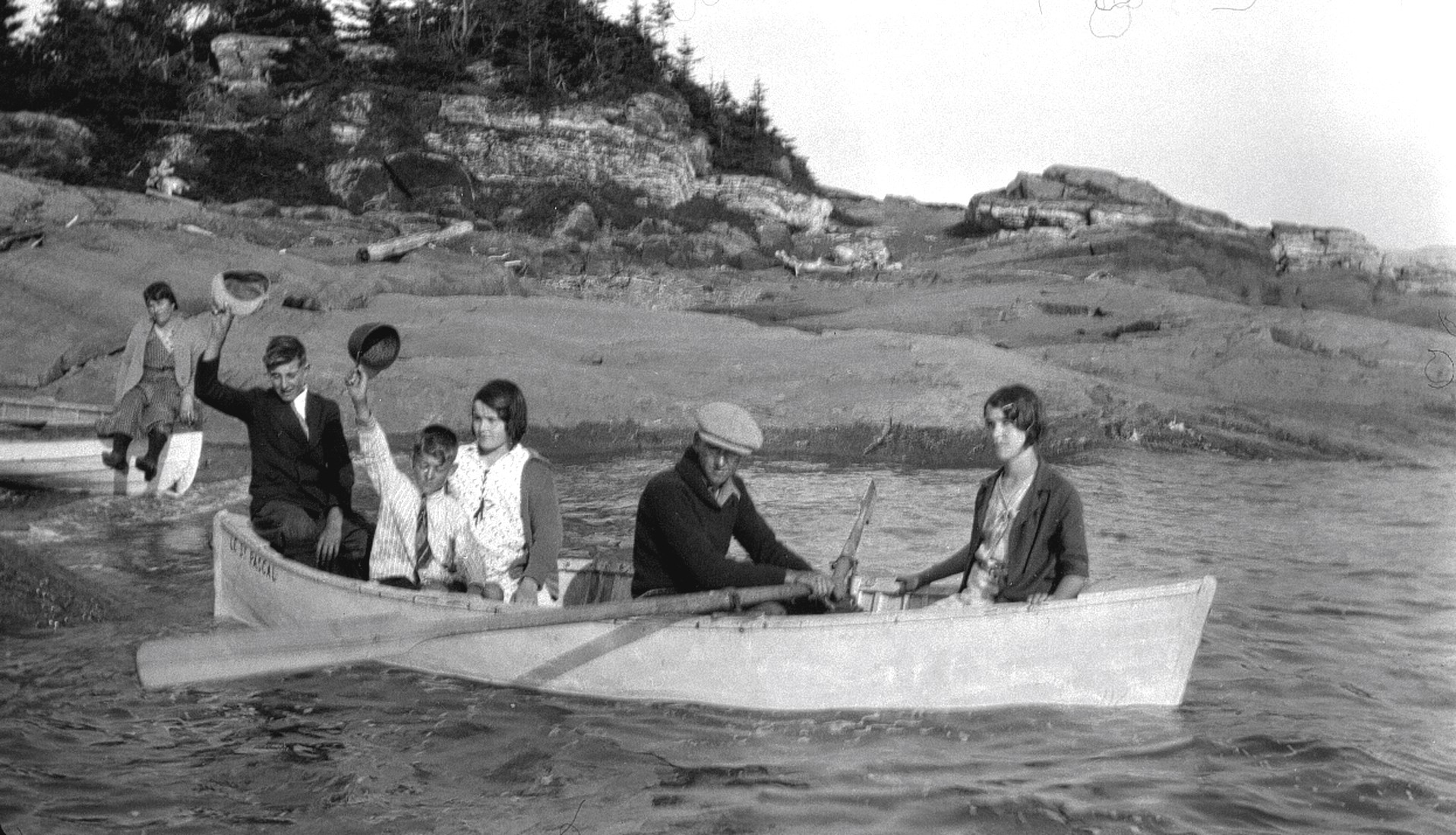

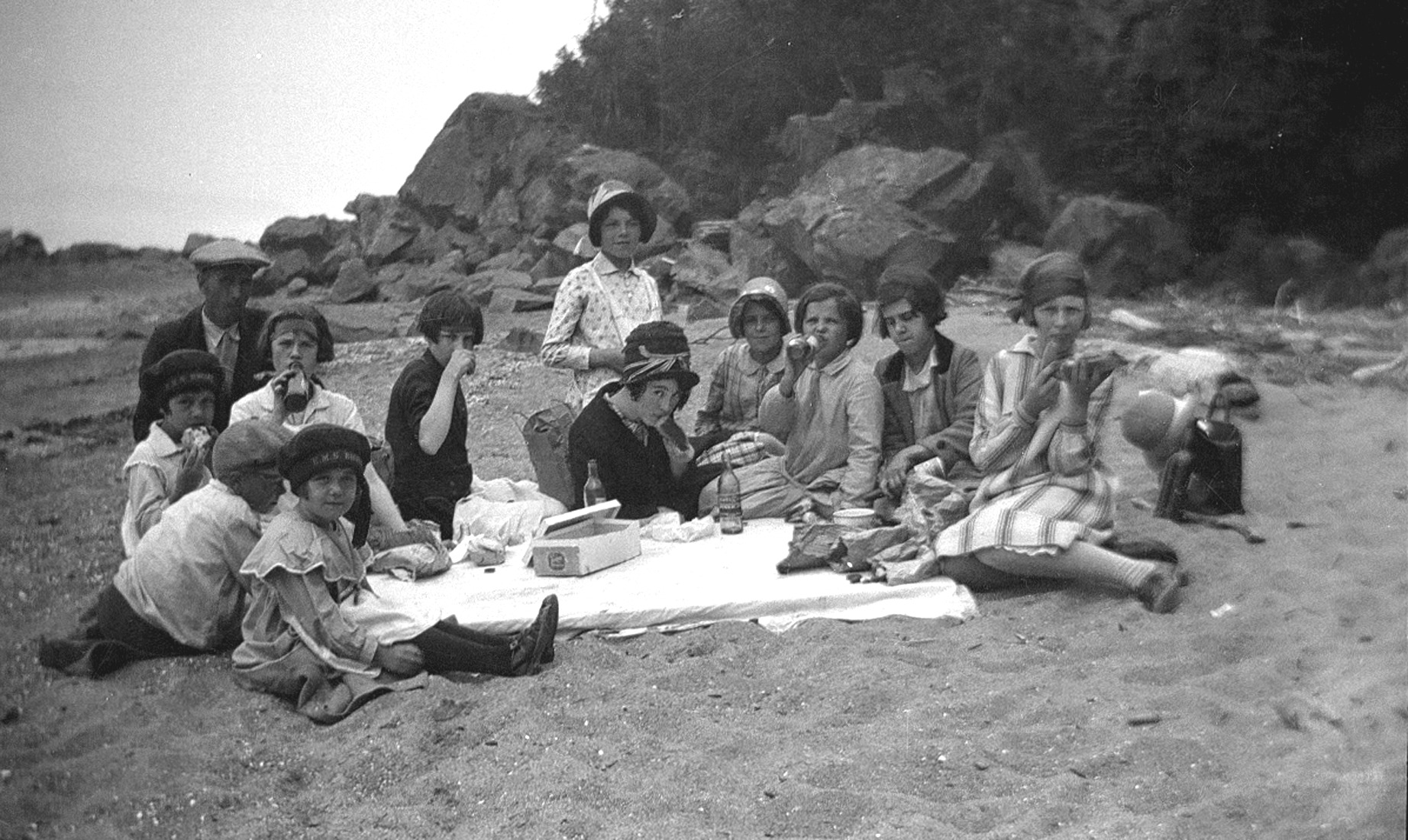

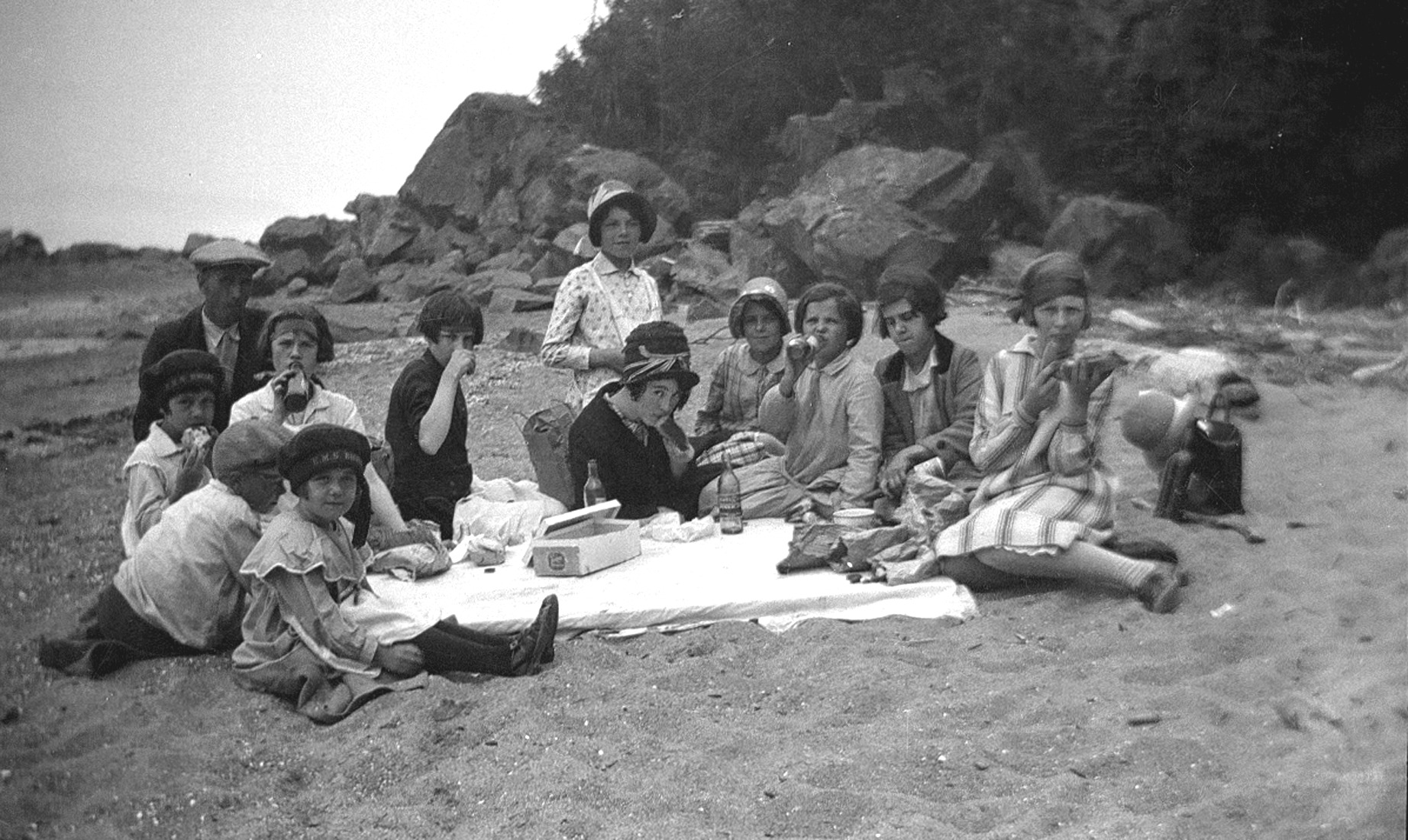

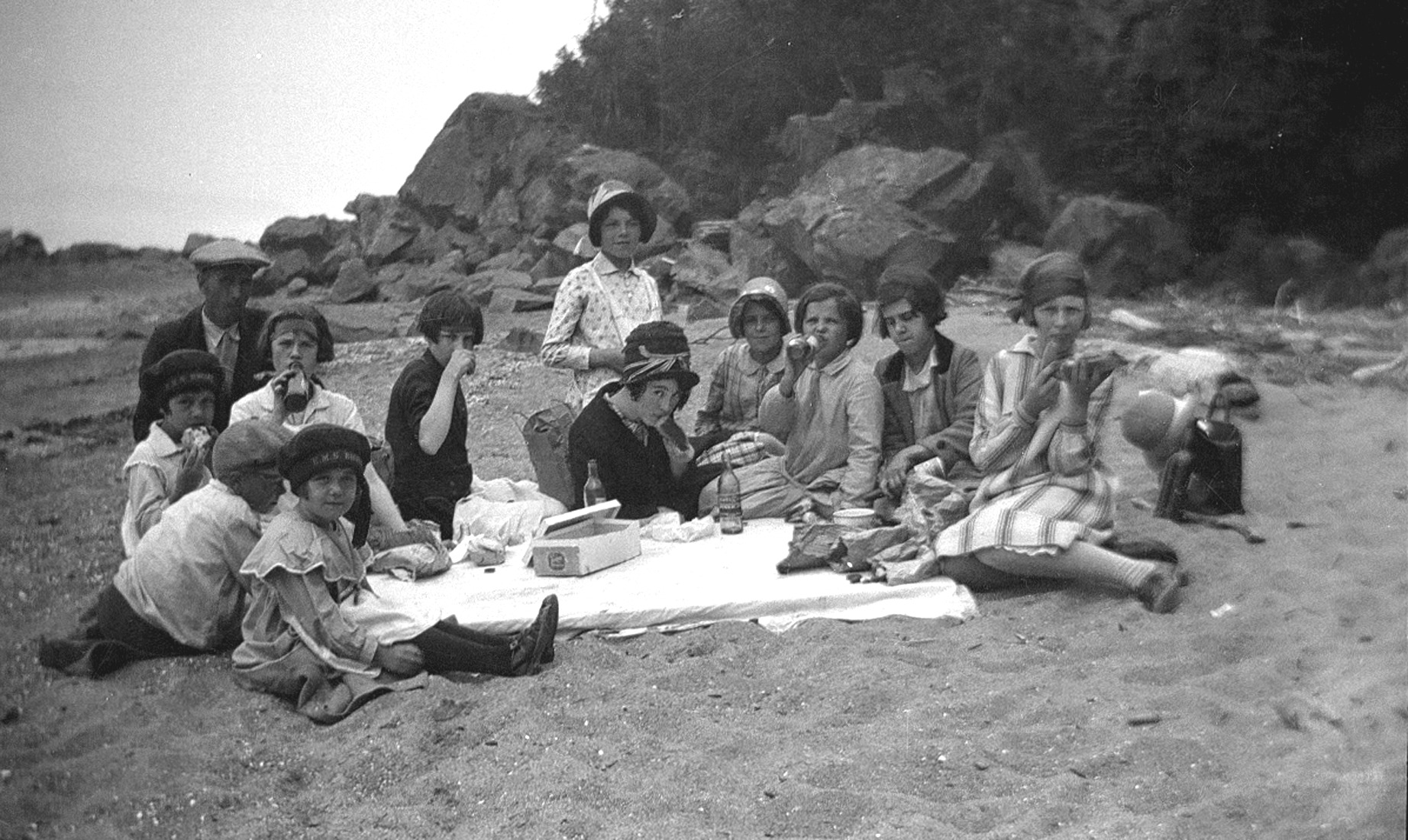

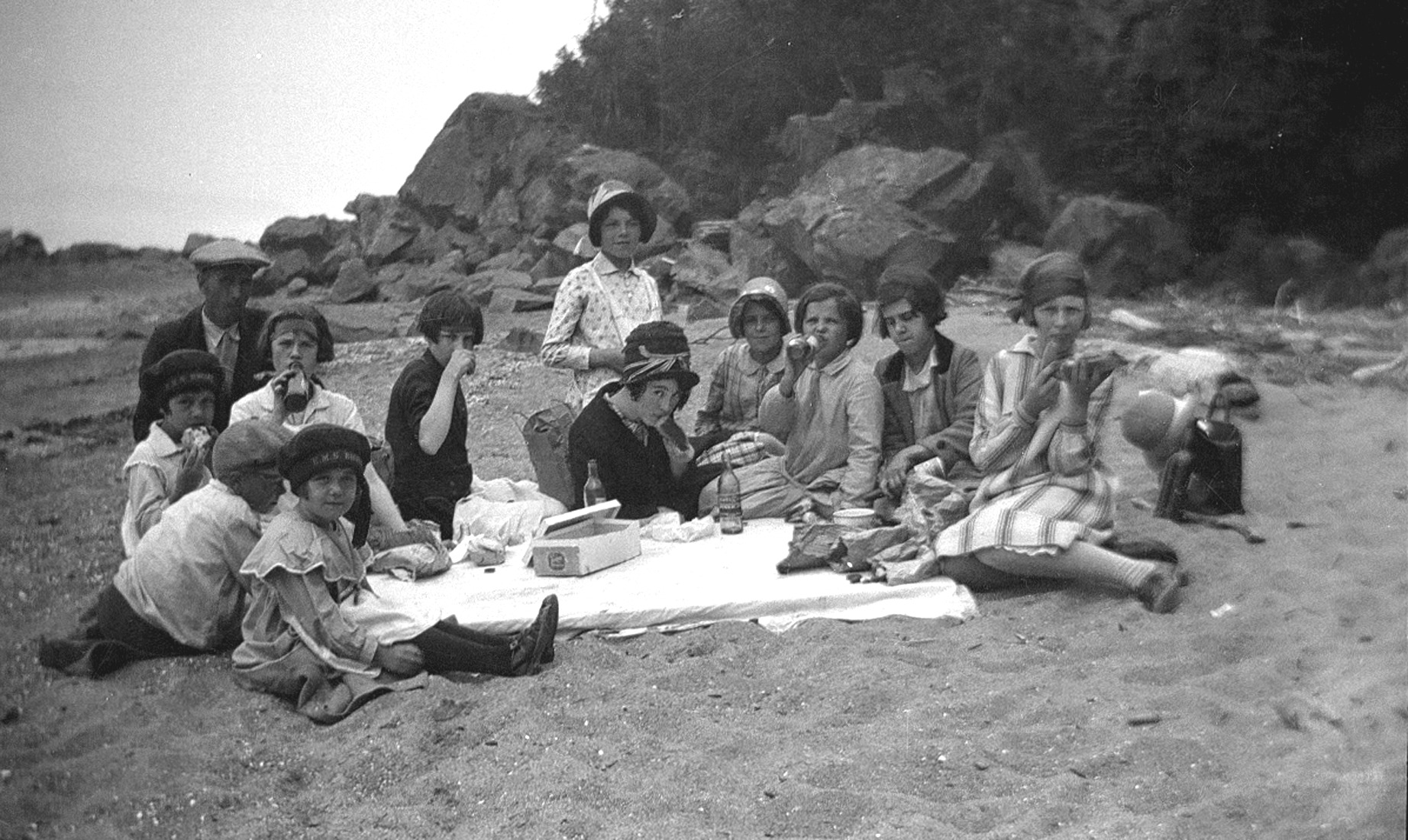

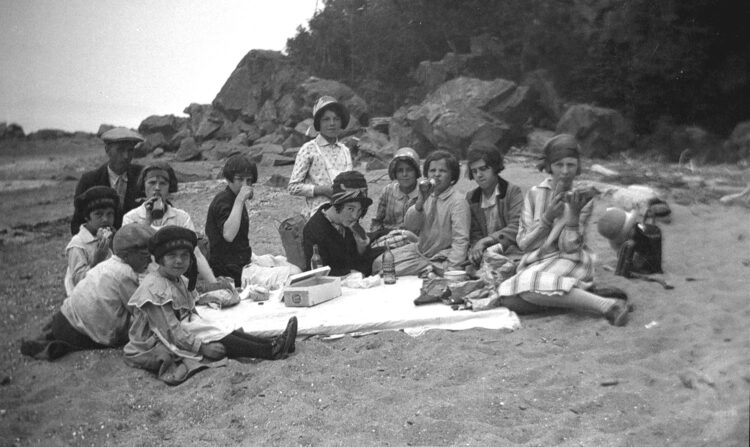

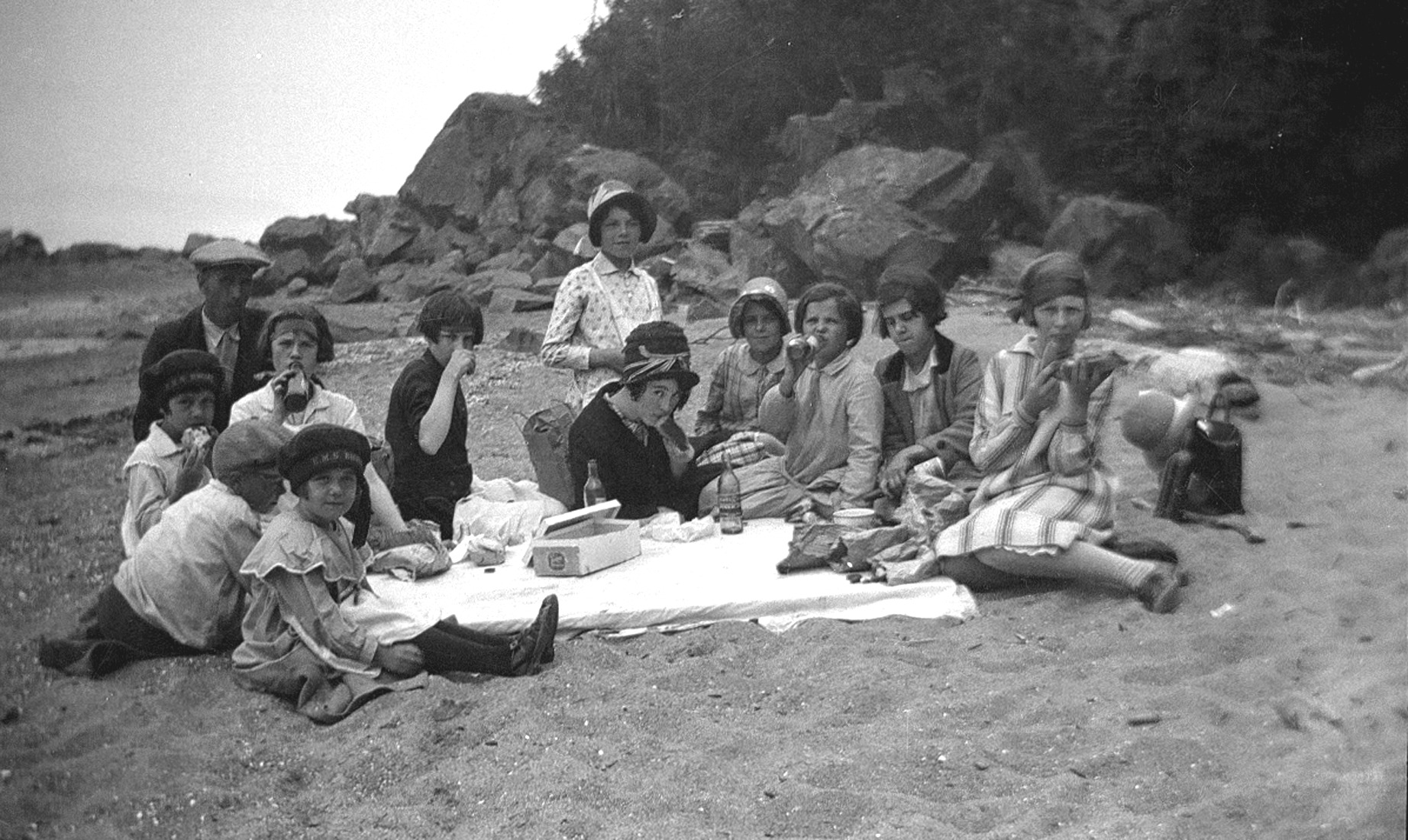

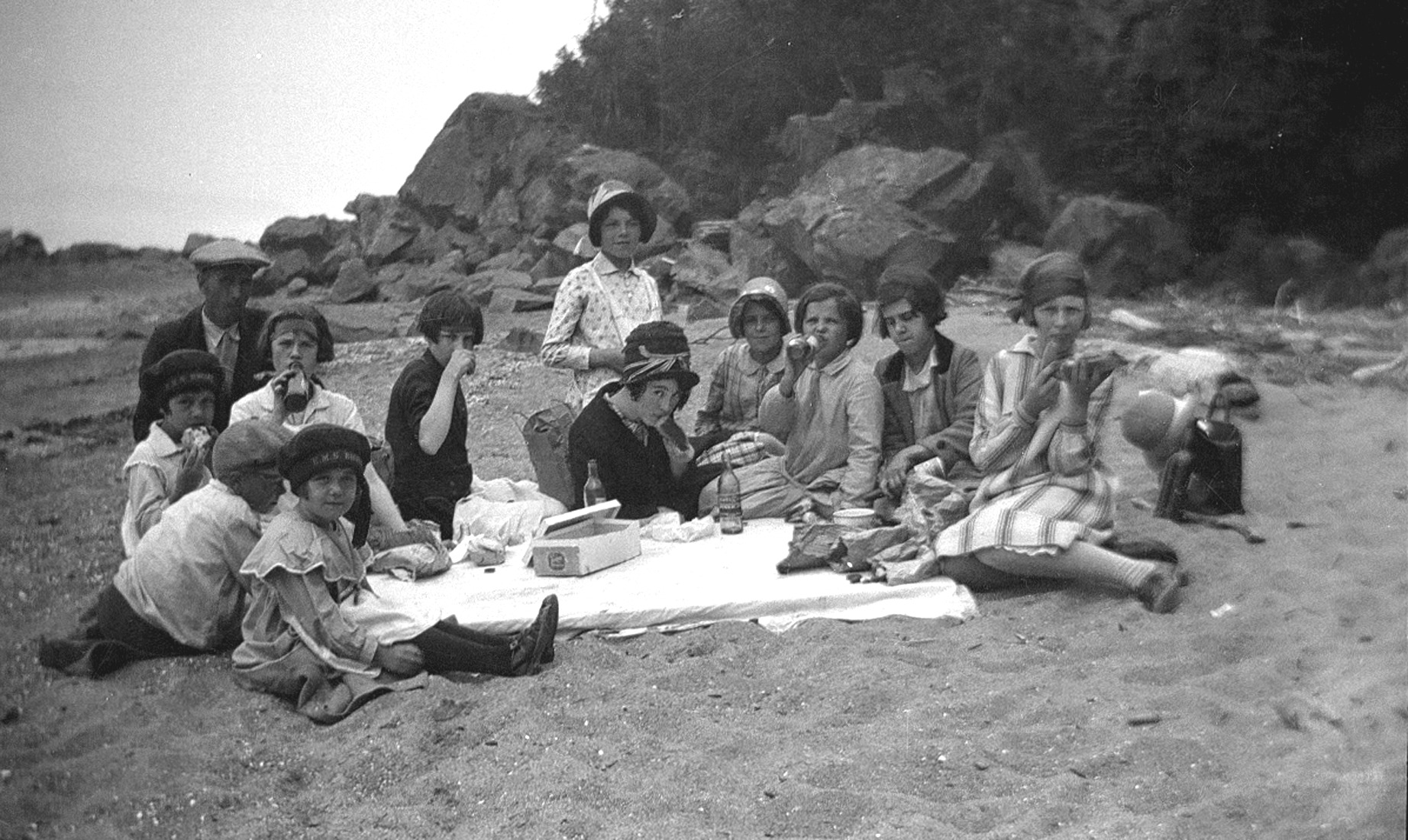

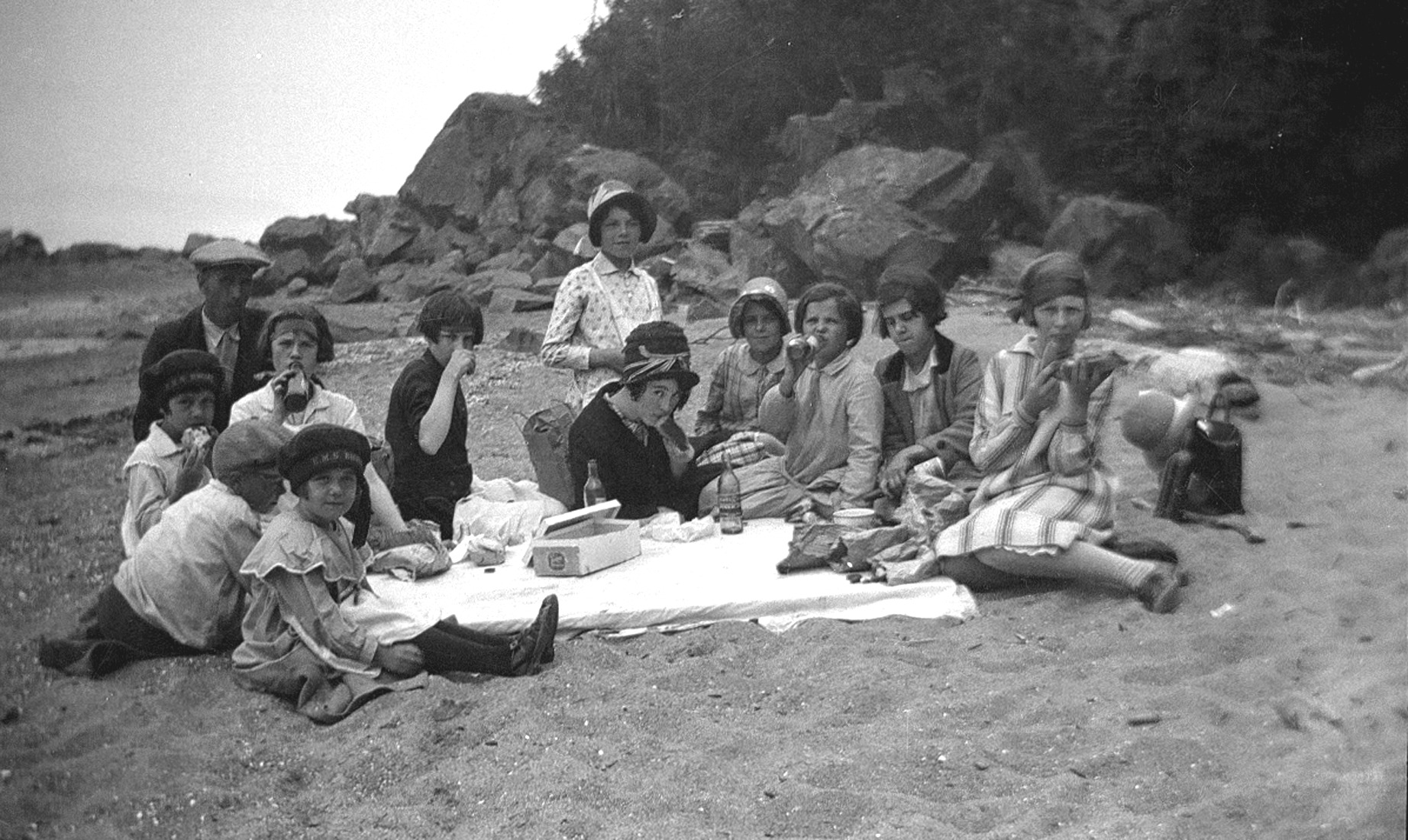

Picnicking on the shoreline was one of the most popular summer activities in Kamouraska during Dumont’s time. At the centre of this photo, lying down, is Rosalie Bergeron, the photographer’s adopted sister.

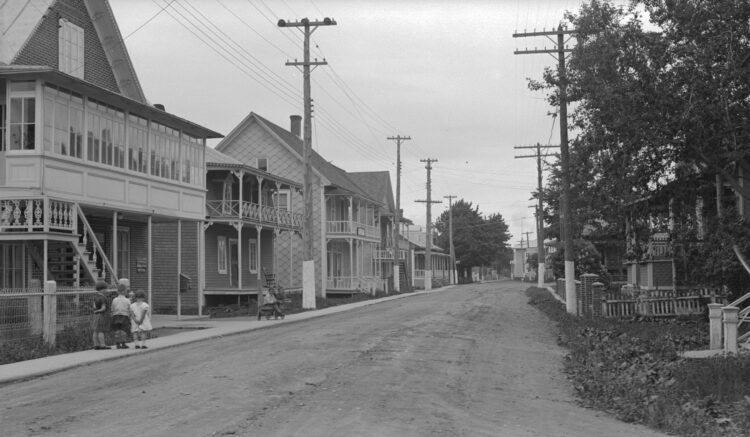

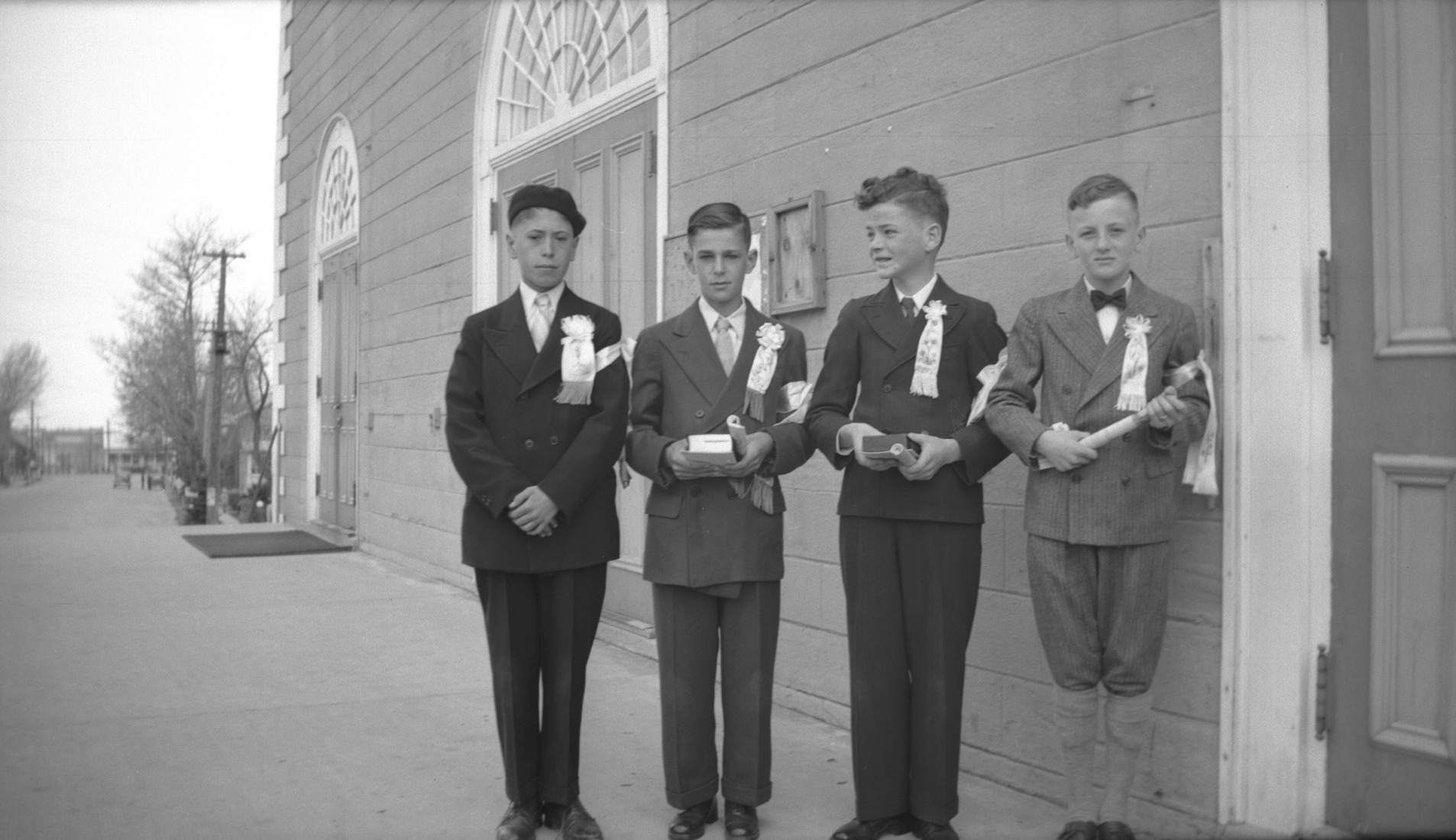

Marie-Alice Dumont’s photography is just as valuable for its artistic beauty as its historical significance. Beyond their visual appeal, her images allow us to step into a bygone era to explore a particular time and place. This section, organized by themes, invites us to discover Marie-Alice Dumont’s Kamouraska: religious life and life in the village, leisure activities and family moments, children, men and women—not to mention the breathtaking landscapes that the region is known for.

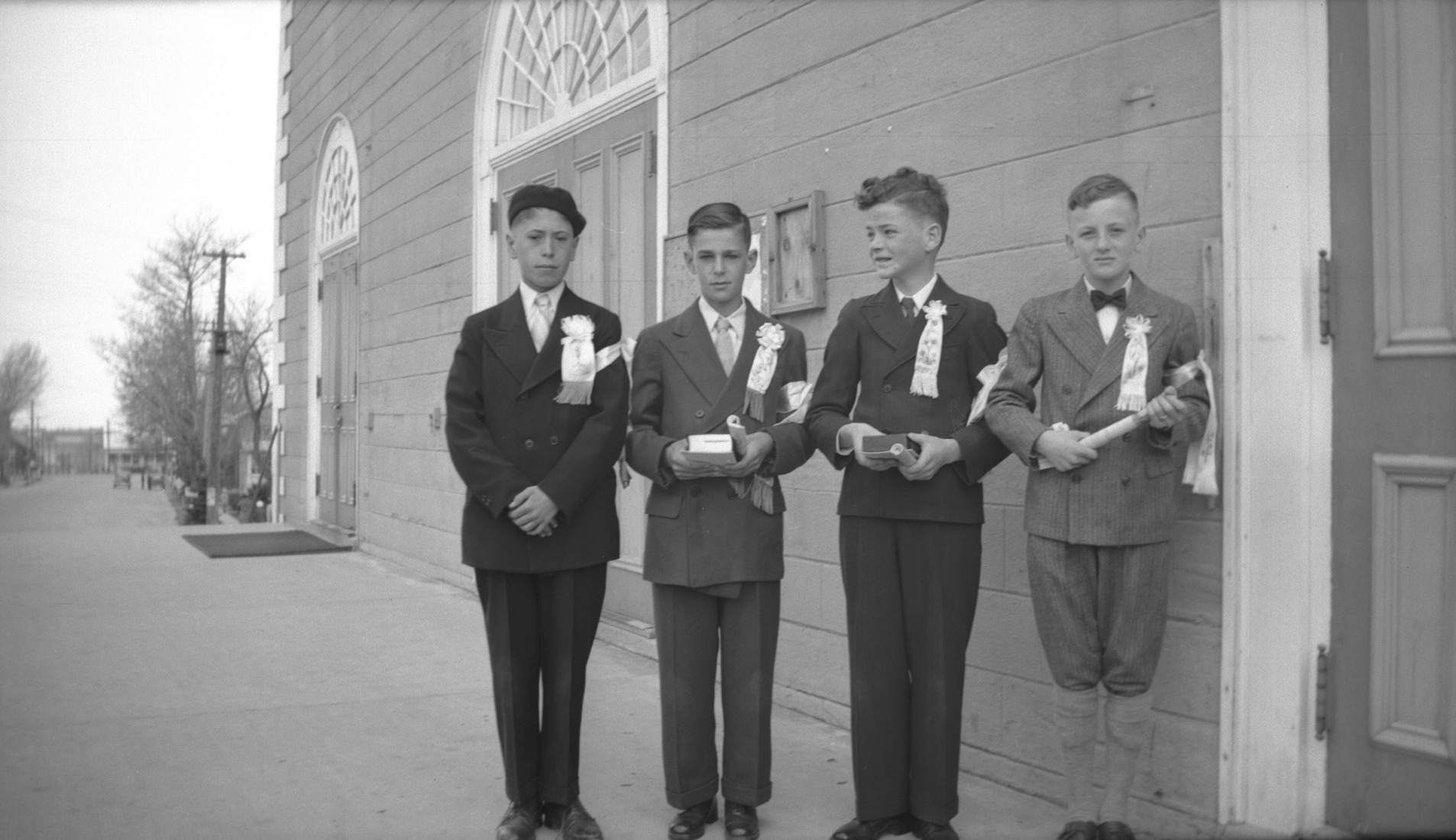

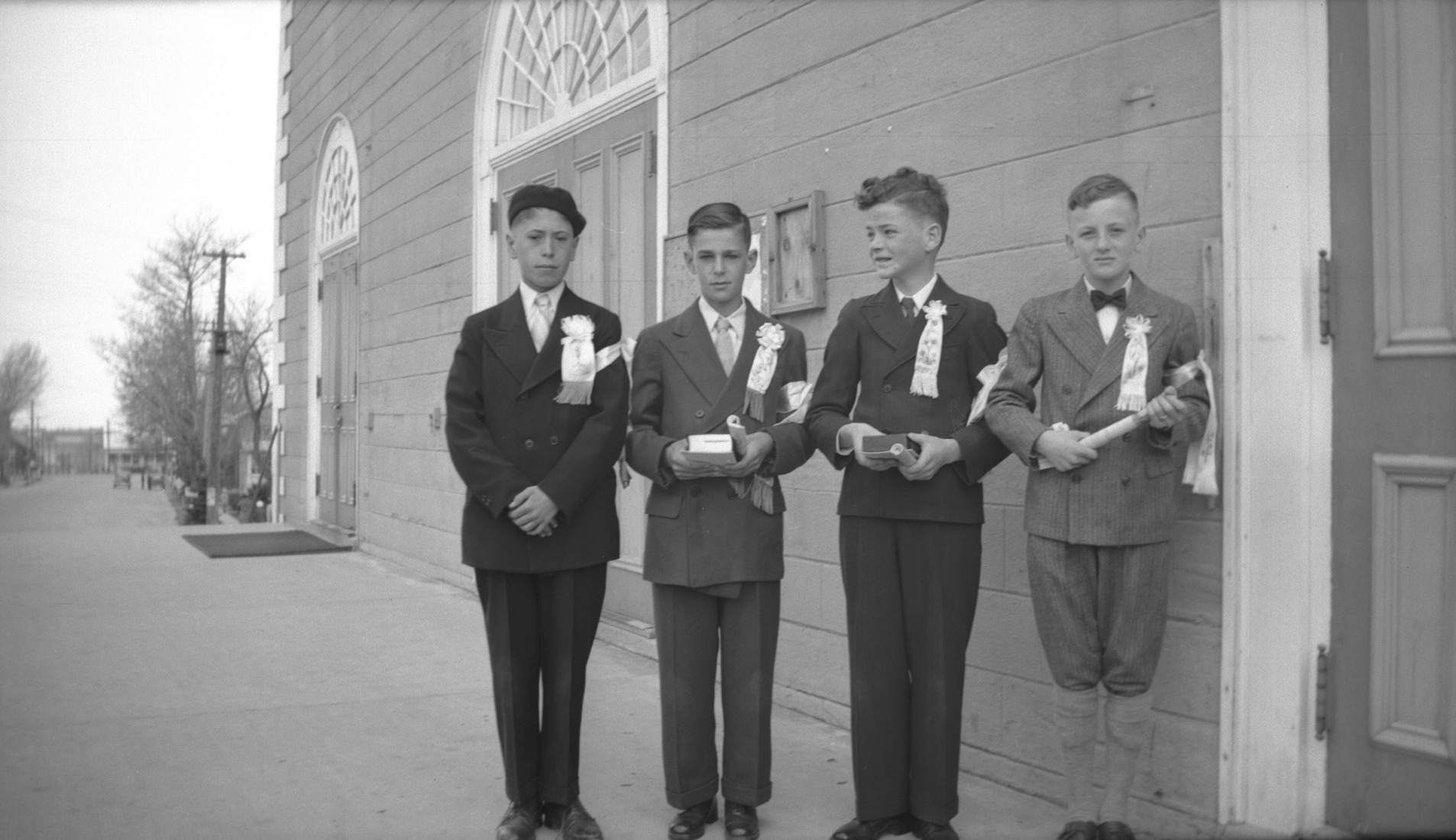

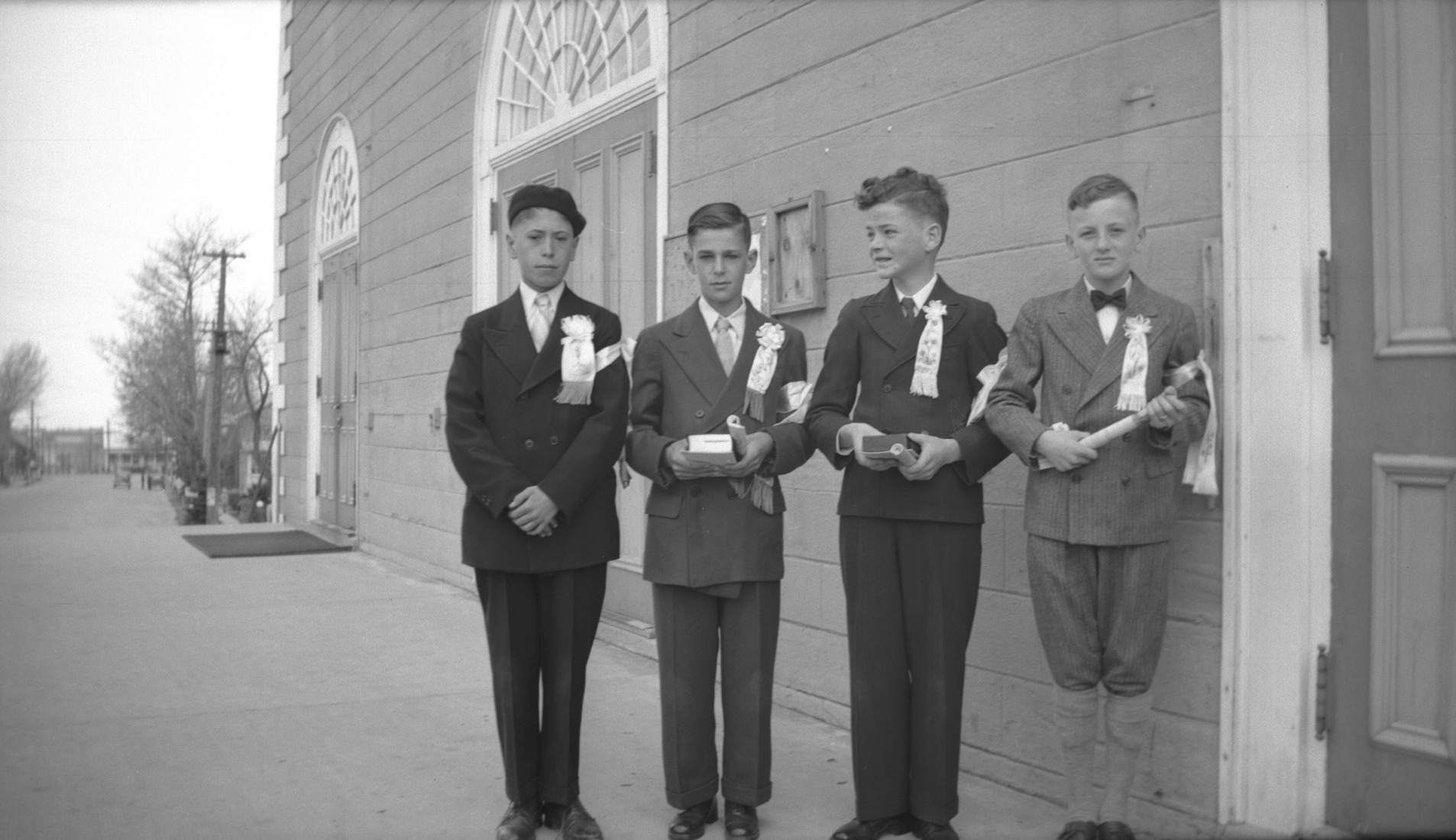

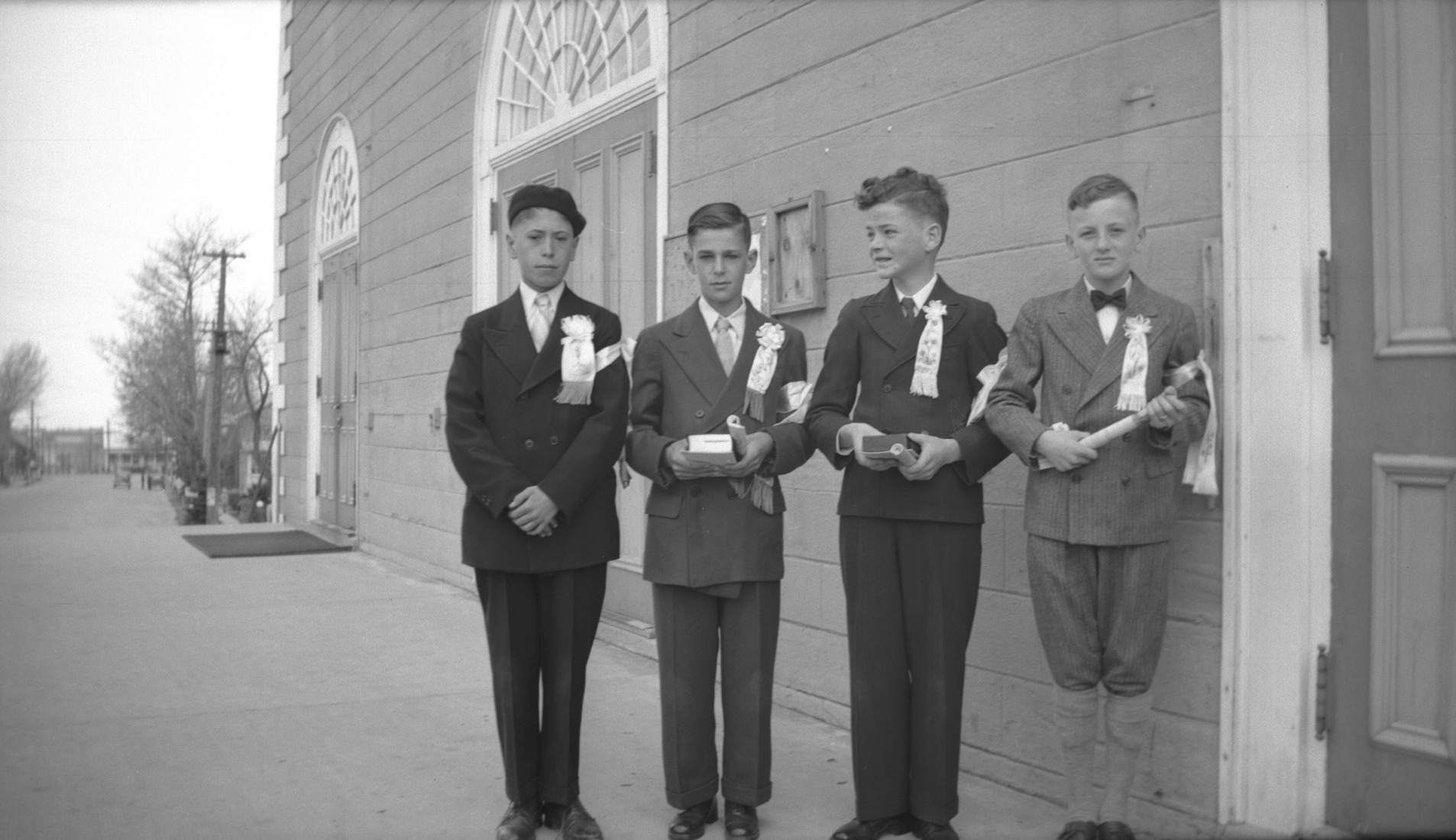

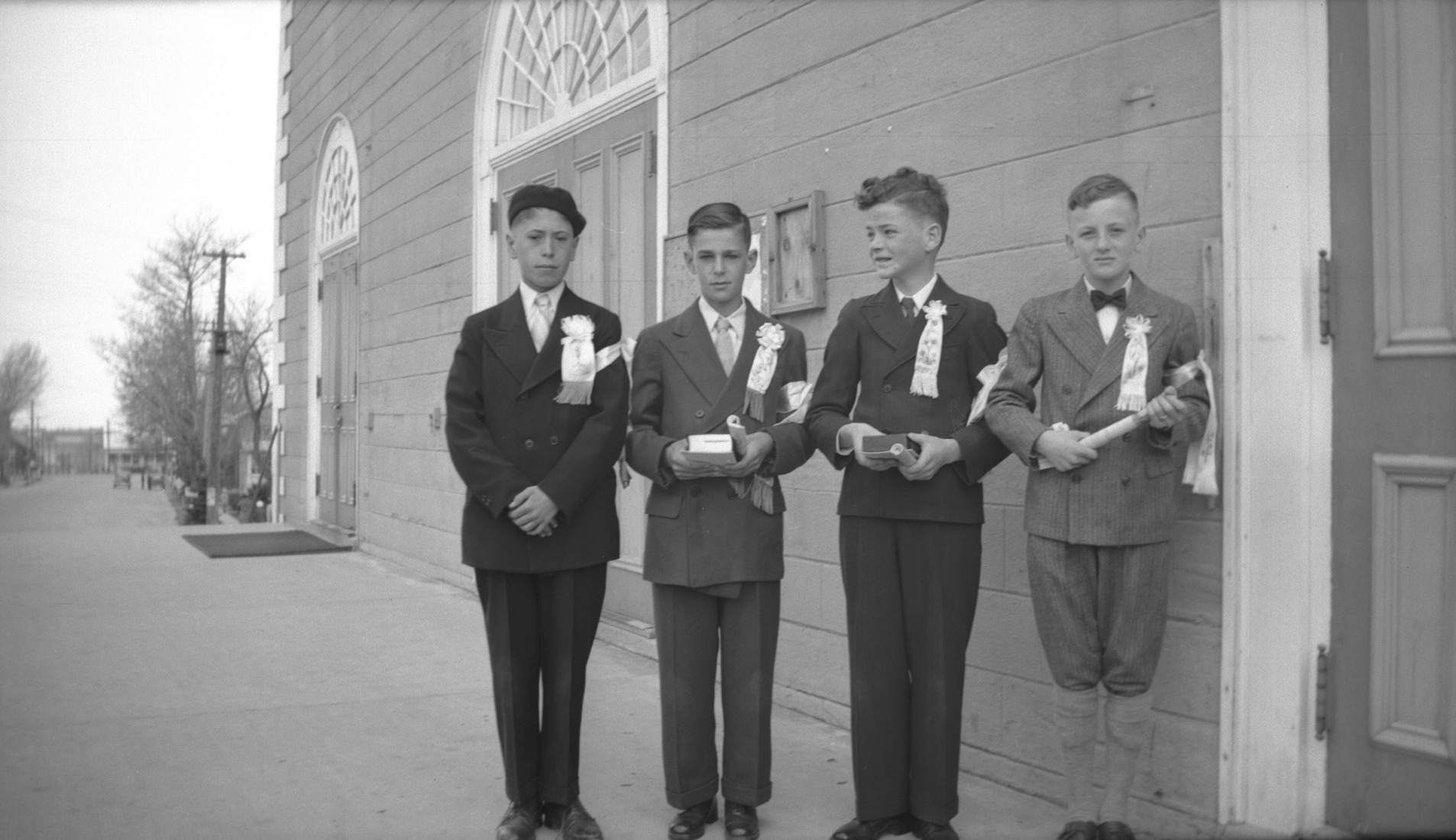

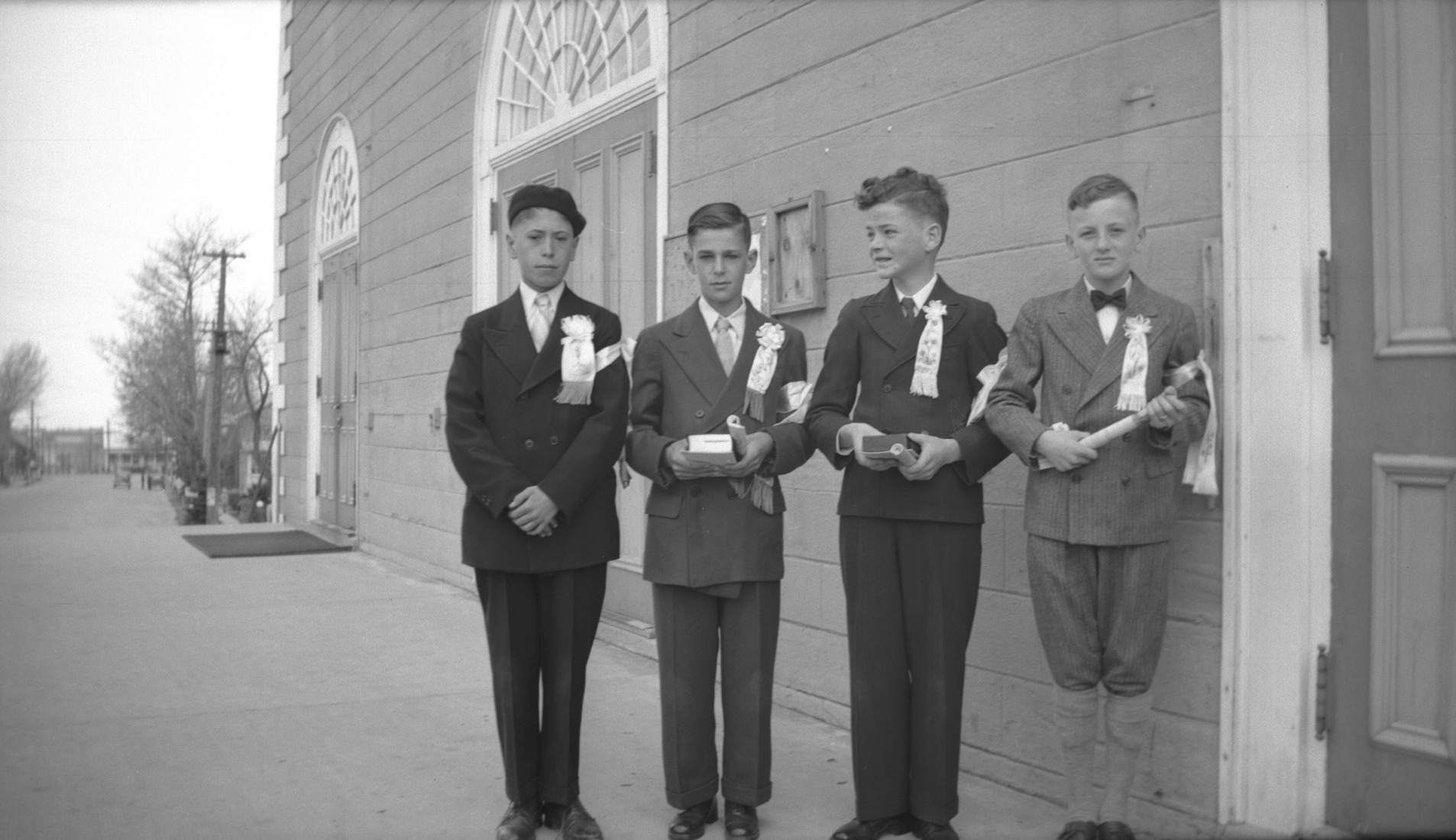

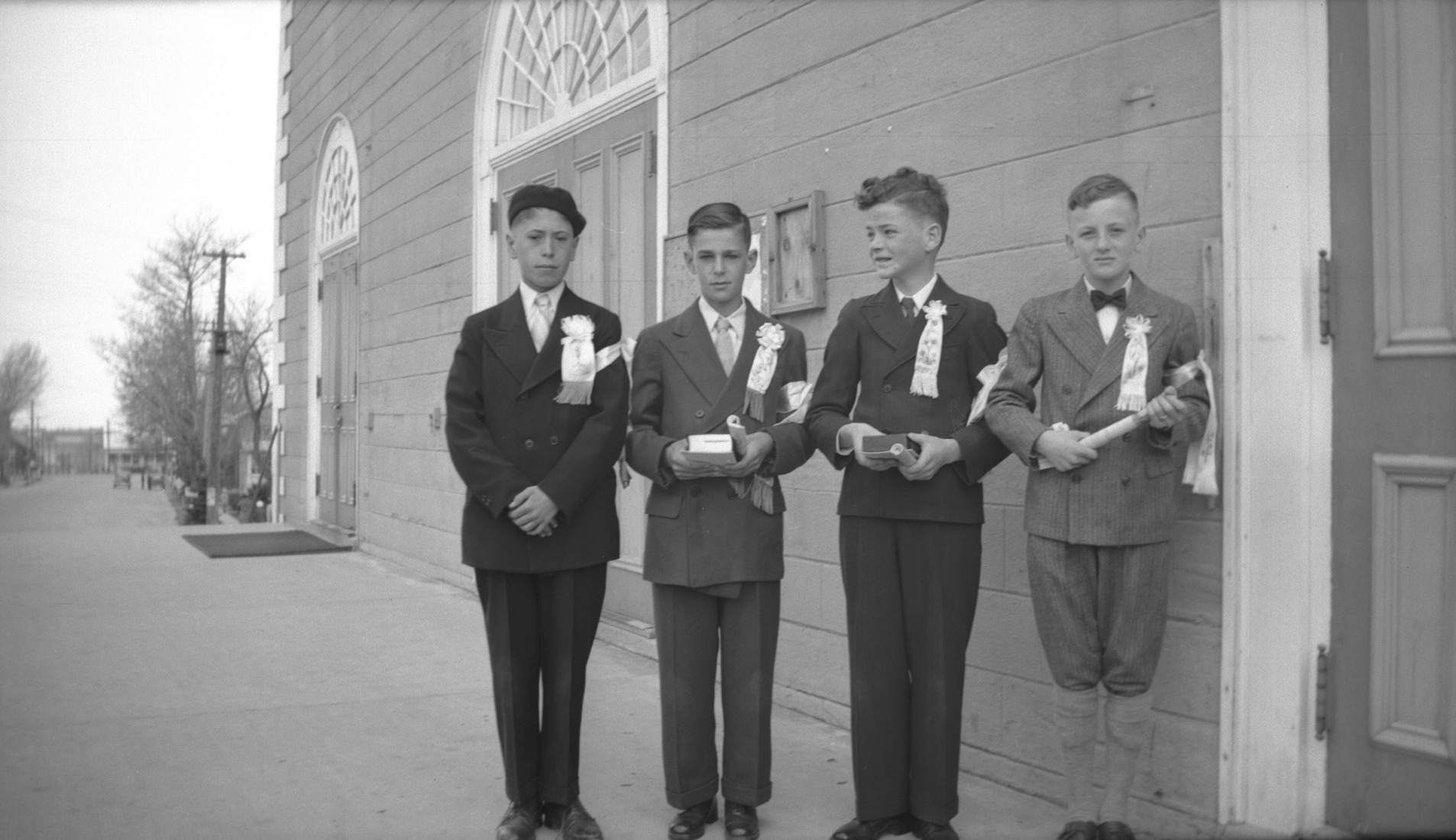

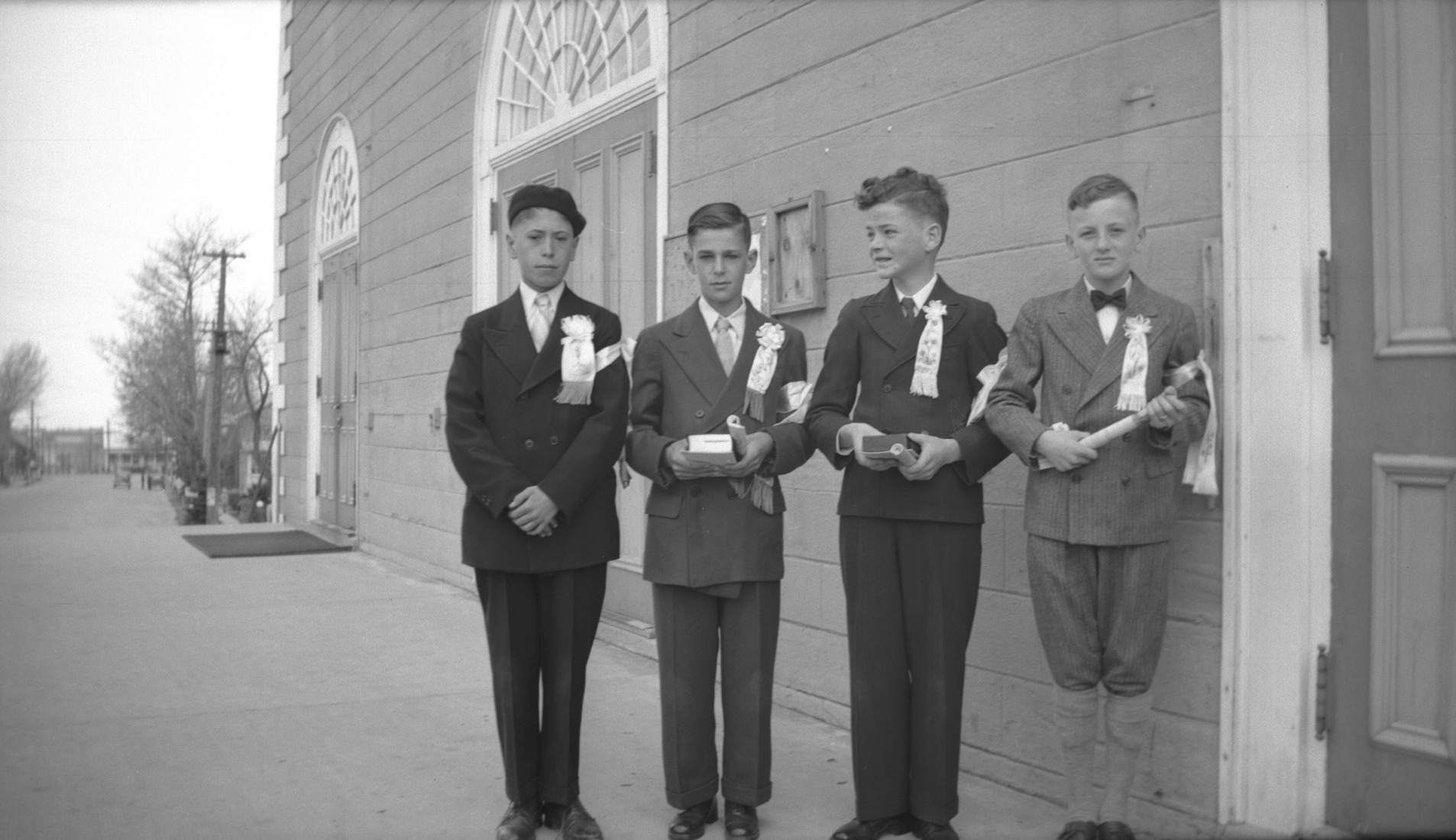

In early 20th-century Kamouraska, most of the community was made up of large French Canadian families living in rural or small-town settings. For these residents, having a portrait taken by a photographer was a big event, and they would often dress up in their finest outfits for a visit to Marie-Alice Dumont. When visiting her siblings, Marie-Alice often brought her camera along to capture them on their land or in front of their home. Families really were the cornerstone of her work.

In rural Quebec, large families remained the norm well into the 1950s. So-called “complete” families, where both parents lived to at least age 50, had, on average, eight or nine children. Marie-Alice Dumont did not have to look far for examples; one of such family was that of her sister Émilia and husband, Flavius Ouellet.

It was common for women to come alone with a baby or young child to be photographed in Dumont’s studio. Here, Mrs. Camille Soucy is pictured with her daughter Françine, who was visiting the studio for the first time. They would return four years later.

This family of 10 children stands proudly in front of their home. One might wonder about the intention behind the composition: nearly half the image is taken up by a large tree!

Here is another example of a large family from Marie-Alice Dumont’s circle: her sister Albertine and husband, Ludger Bérubé. The seven adults standing with them are their children who went on to pursue religious vocations.

Émile Boucher and Gabrielle Dumont, another of the photographer’s sisters, are shown here with their first nine children. (They would eventually have 16). Remarkably, among their children, eight daughters became nuns and one son became a priest.

Alexandre Bérubé and Yvonne Léveillé, pictured here with their children, used this photograph in their “homage to local families,” featured in the centennial album of Saint-Alexandre in 1952.

It was common for women to come alone with a baby or young child to be photographed in Dumont’s studio. Here, Mrs. Camille Soucy is pictured with her daughter Françine, who was visiting the studio for the first time. They would return four years later.

This family of 10 children stands proudly in front of their home. One might wonder about the intention behind the composition: nearly half the image is taken up by a large tree!

Here is another example of a large family from Marie-Alice Dumont’s circle: her sister Albertine and husband, Ludger Bérubé. The seven adults standing with them are their children who went on to pursue religious vocations.

Émile Boucher and Gabrielle Dumont, another of the photographer’s sisters, are shown here with their first nine children. (They would eventually have 16). Remarkably, among their children, eight daughters became nuns and one son became a priest.

Alexandre Bérubé and Yvonne Léveillé, pictured here with their children, used this photograph in their “homage to local families,” featured in the centennial album of Saint-Alexandre in 1952.

It was common for women to come alone with a baby or young child to be photographed in Dumont’s studio. Here, Mrs. Camille Soucy is pictured with her daughter Françine, who was visiting the studio for the first time. They would return four years later.

This family of 10 children stands proudly in front of their home. One might wonder about the intention behind the composition: nearly half the image is taken up by a large tree!

Here is another example of a large family from Marie-Alice Dumont’s circle: her sister Albertine and husband, Ludger Bérubé. The seven adults standing with them are their children who went on to pursue religious vocations.

Émile Boucher and Gabrielle Dumont, another of the photographer’s sisters, are shown here with their first nine children. (They would eventually have 16). Remarkably, among their children, eight daughters became nuns and one son became a priest.

Alexandre Bérubé and Yvonne Léveillé, pictured here with their children, used this photograph in their “homage to local families,” featured in the centennial album of Saint-Alexandre in 1952.

It was common for women to come alone with a baby or young child to be photographed in Dumont’s studio. Here, Mrs. Camille Soucy is pictured with her daughter Françine, who was visiting the studio for the first time. They would return four years later.

This family of 10 children stands proudly in front of their home. One might wonder about the intention behind the composition: nearly half the image is taken up by a large tree!

Here is another example of a large family from Marie-Alice Dumont’s circle: her sister Albertine and husband, Ludger Bérubé. The seven adults standing with them are their children who went on to pursue religious vocations.

Émile Boucher and Gabrielle Dumont, another of the photographer’s sisters, are shown here with their first nine children. (They would eventually have 16). Remarkably, among their children, eight daughters became nuns and one son became a priest.

Alexandre Bérubé and Yvonne Léveillé, pictured here with their children, used this photograph in their “homage to local families,” featured in the centennial album of Saint-Alexandre in 1952.

It was common for women to come alone with a baby or young child to be photographed in Dumont’s studio. Here, Mrs. Camille Soucy is pictured with her daughter Françine, who was visiting the studio for the first time. They would return four years later.

This family of 10 children stands proudly in front of their home. One might wonder about the intention behind the composition: nearly half the image is taken up by a large tree!

Here is another example of a large family from Marie-Alice Dumont’s circle: her sister Albertine and husband, Ludger Bérubé. The seven adults standing with them are their children who went on to pursue religious vocations.

Émile Boucher and Gabrielle Dumont, another of the photographer’s sisters, are shown here with their first nine children. (They would eventually have 16). Remarkably, among their children, eight daughters became nuns and one son became a priest.

Alexandre Bérubé and Yvonne Léveillé, pictured here with their children, used this photograph in their “homage to local families,” featured in the centennial album of Saint-Alexandre in 1952.

Women held a central role in Marie-Alice Dumont’s photography. As the backbone of family life in early 20th-century Kamouraska, they frequently starred in studio portraits celebrating motherhood and family ties. But her focus was not only on domestic life—she also captured women in other contexts. In some images, they can be seen working or at leisure. As a versatile photographer, Dumont offers us precious snapshots of daily life from a woman’s perspective.

The photographer chose to portray Dolorès Garneau in a pose that reflects her profession. With pencil in hand, an open book in front of her and a thoughtful posture, the schoolteacher appears to be preparing a lesson.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

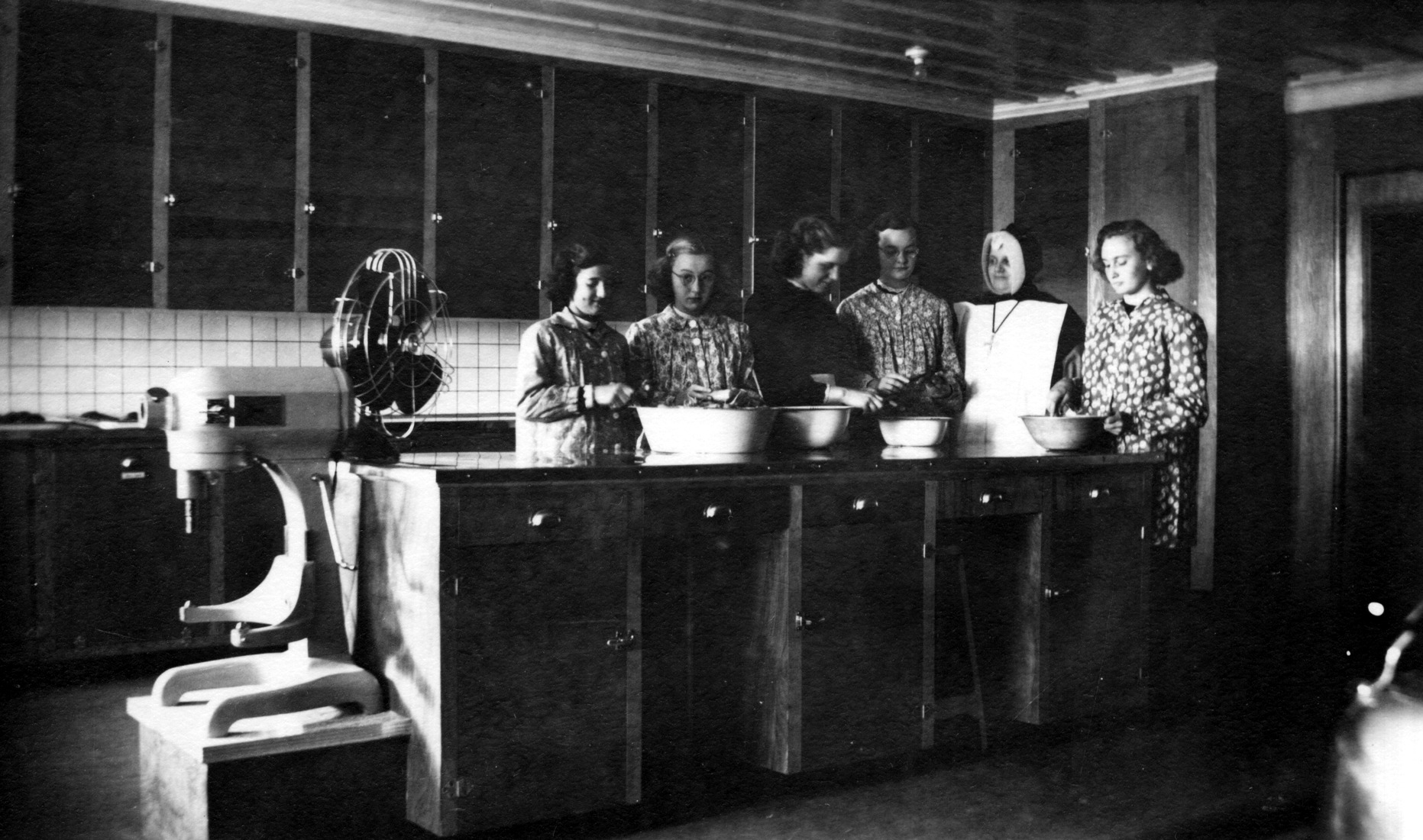

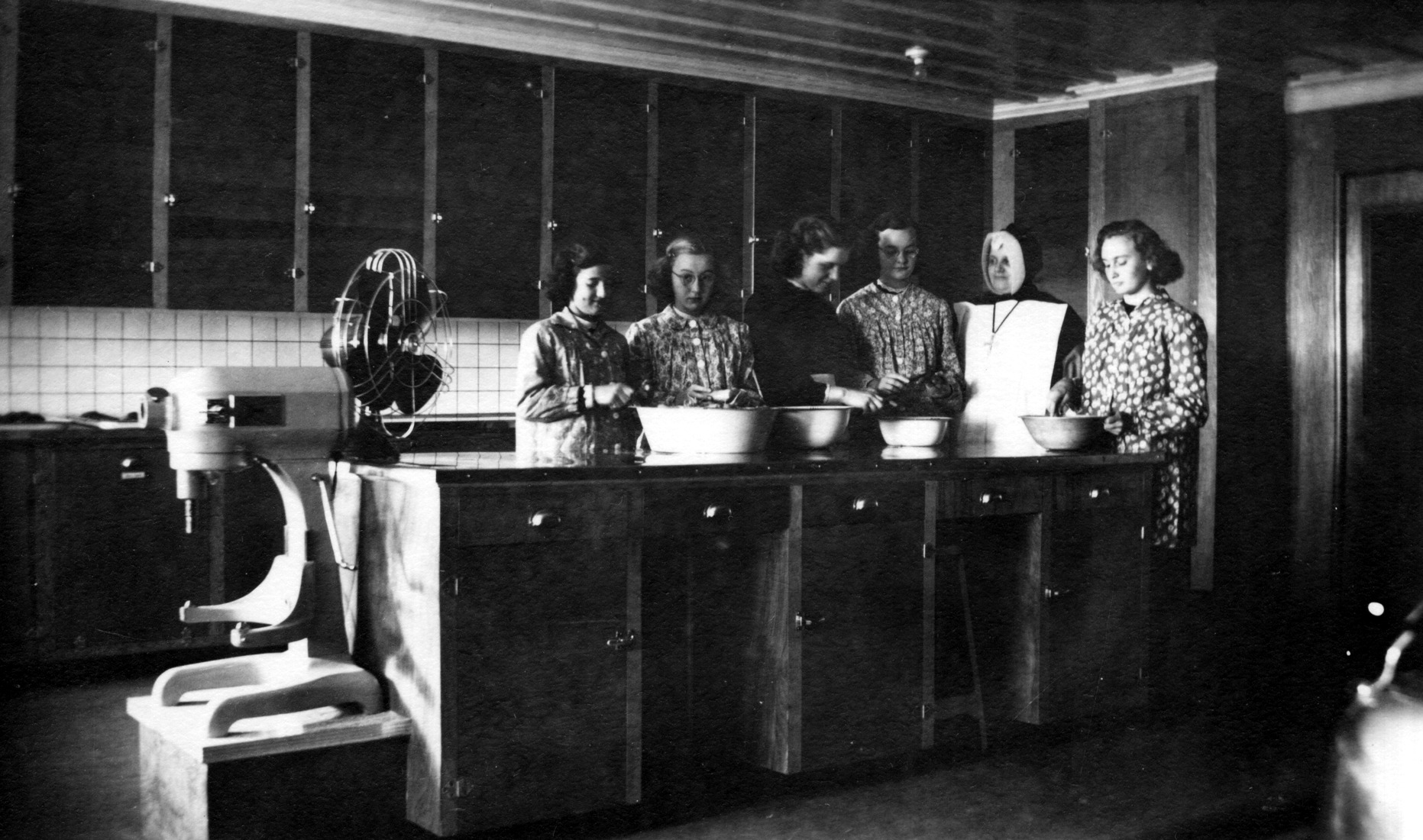

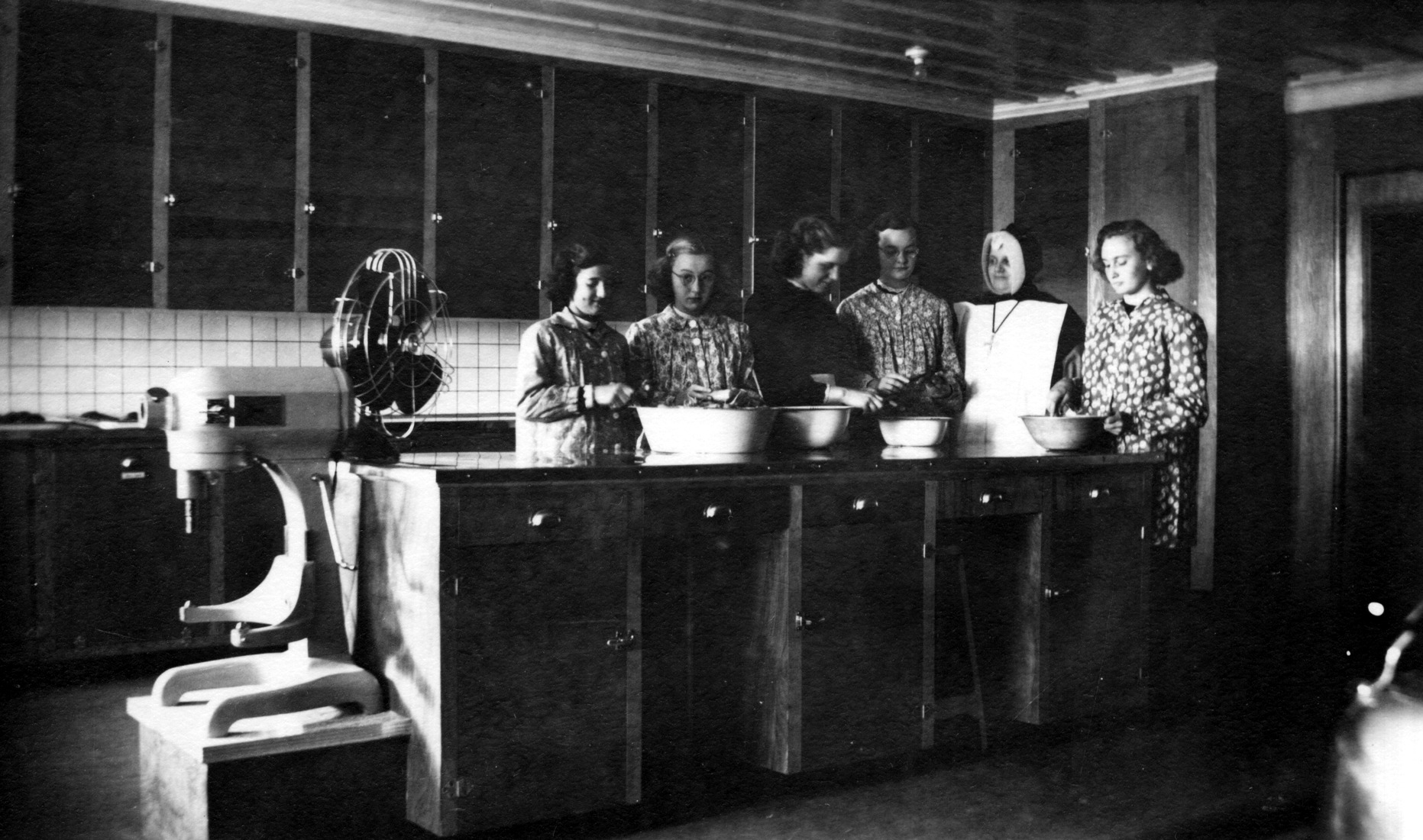

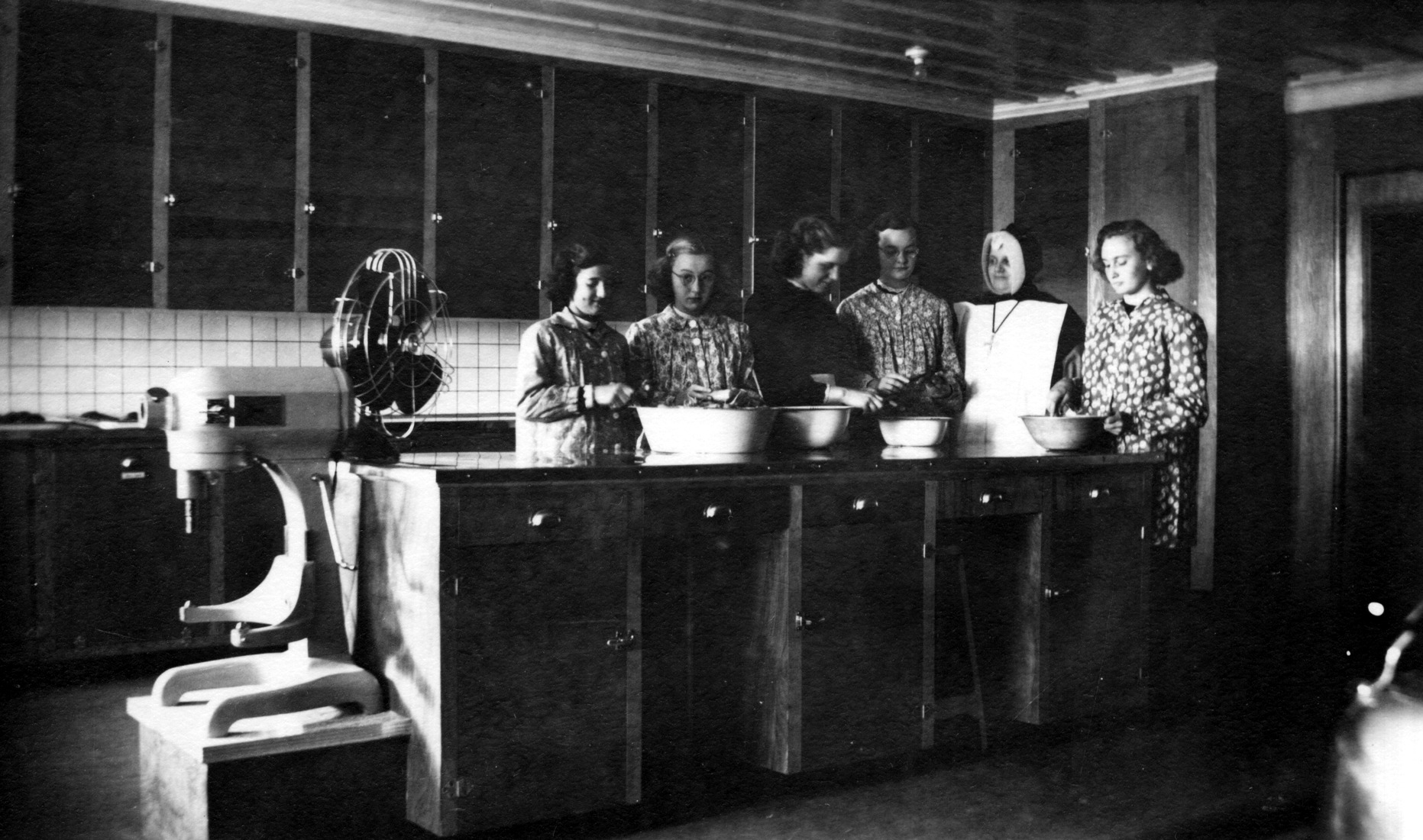

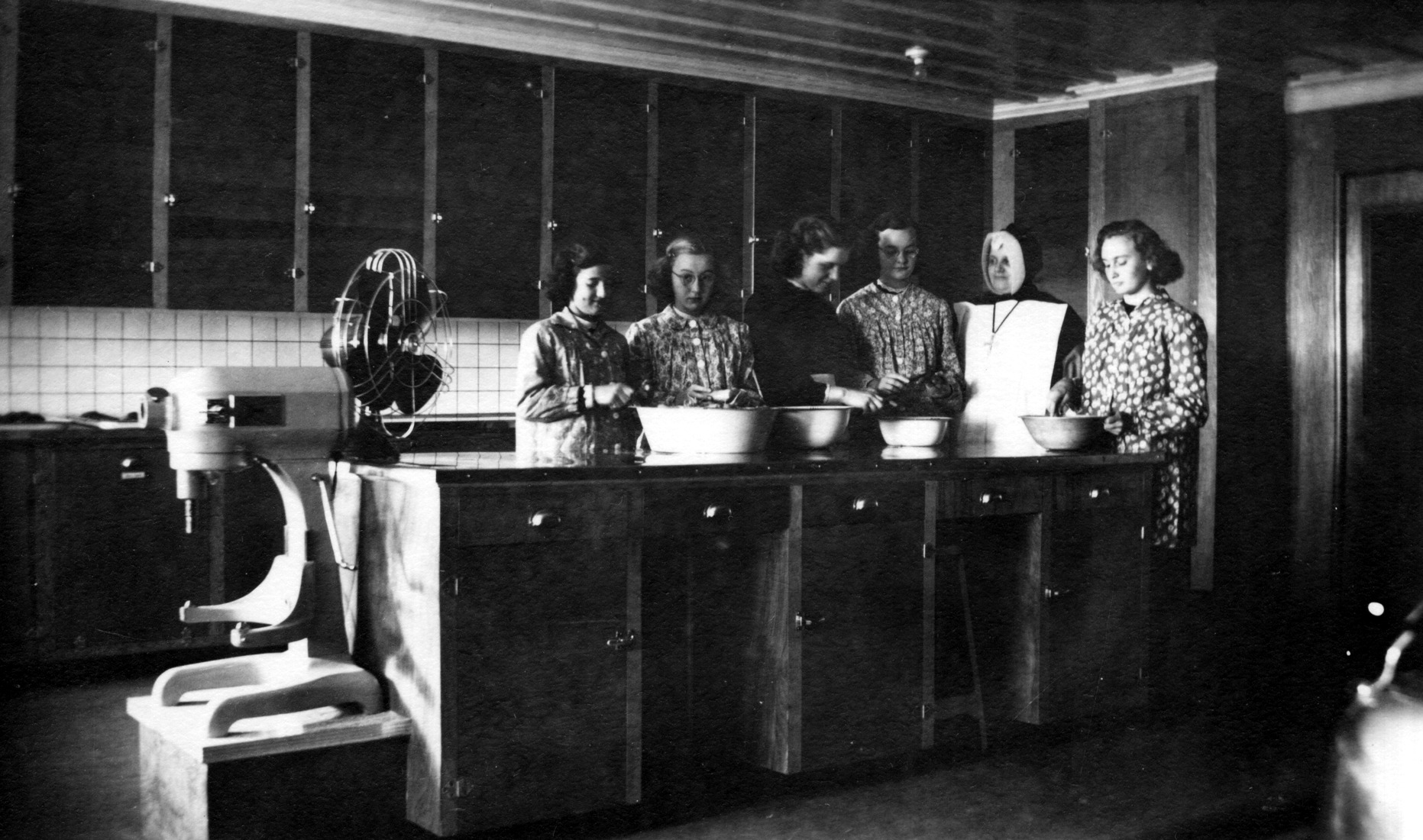

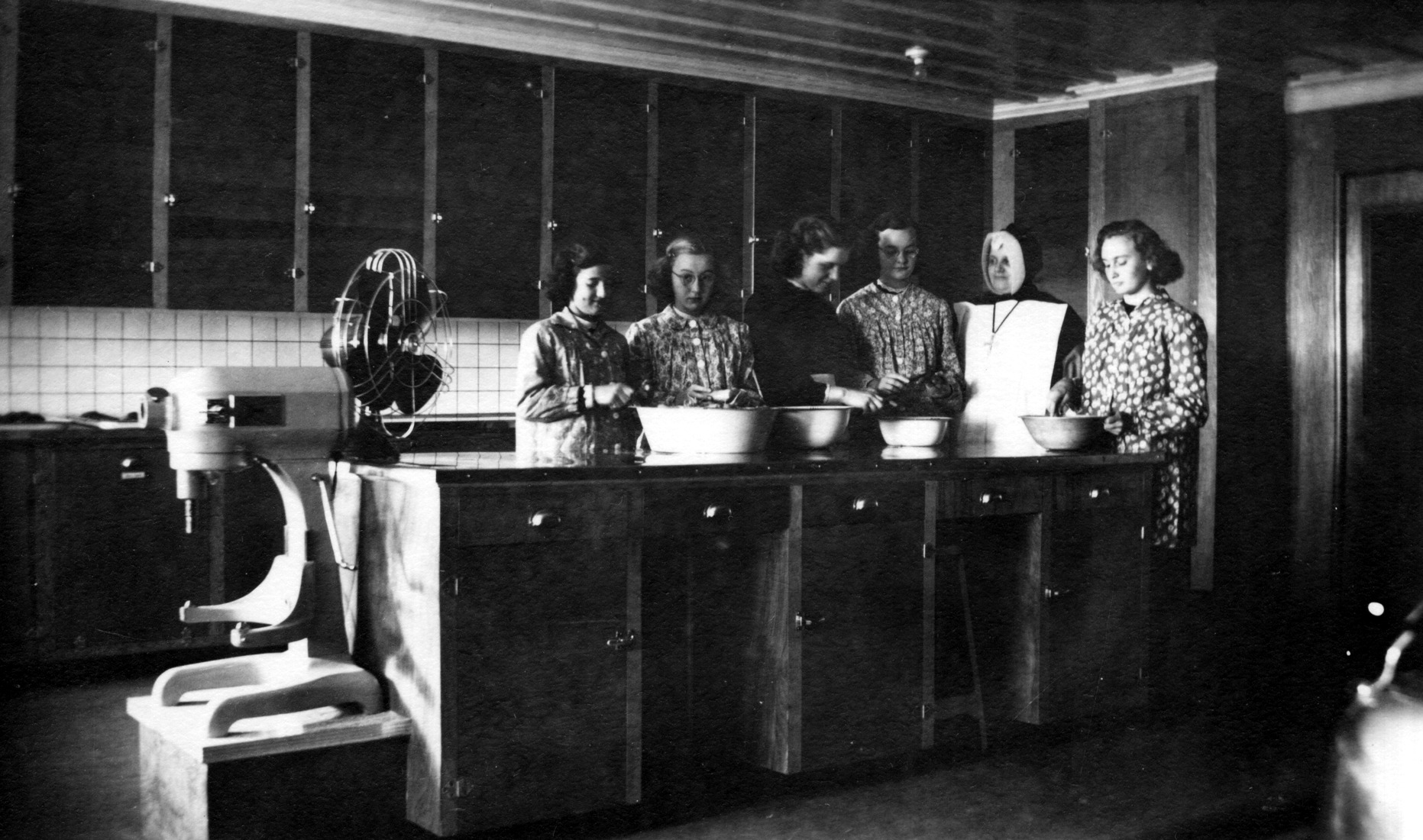

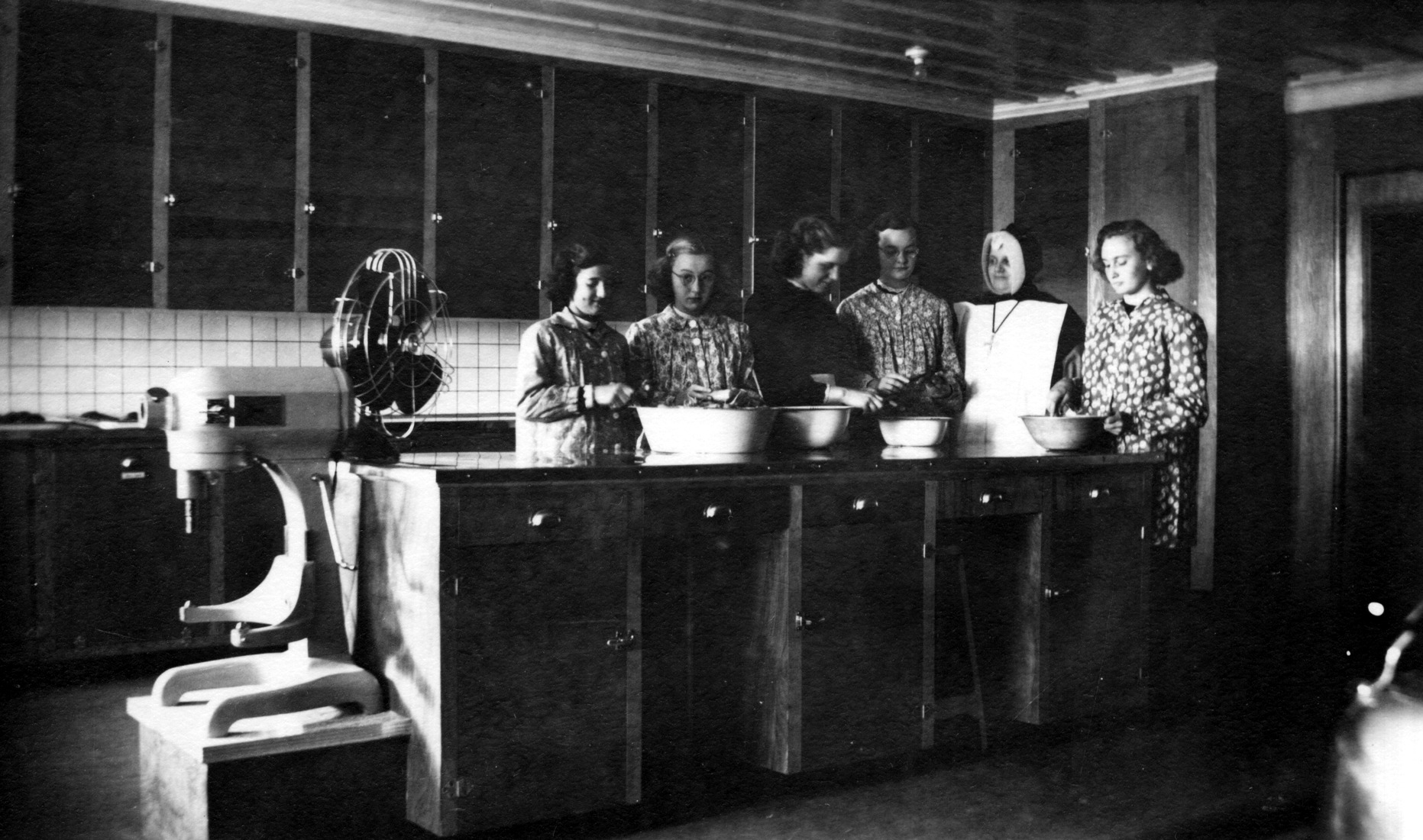

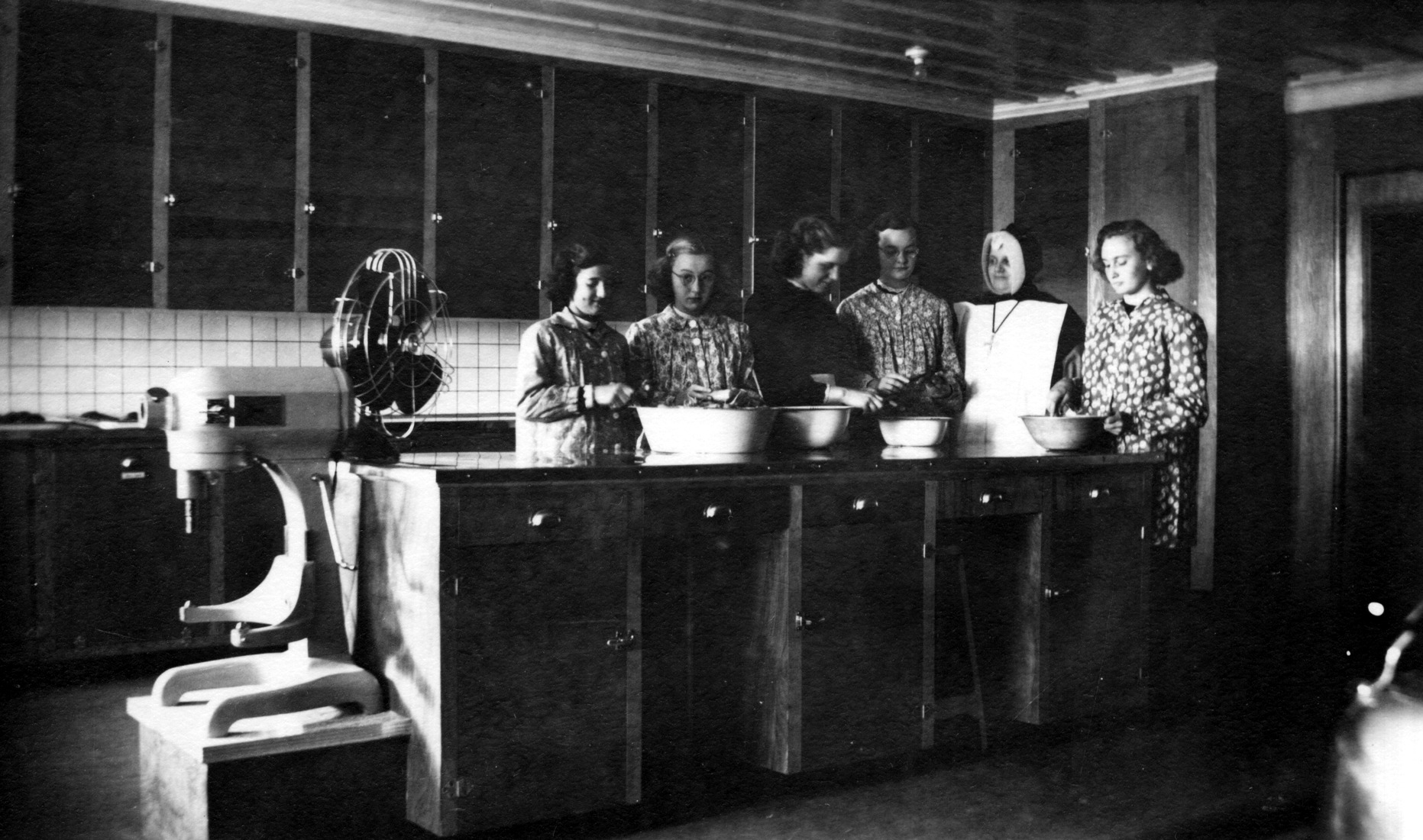

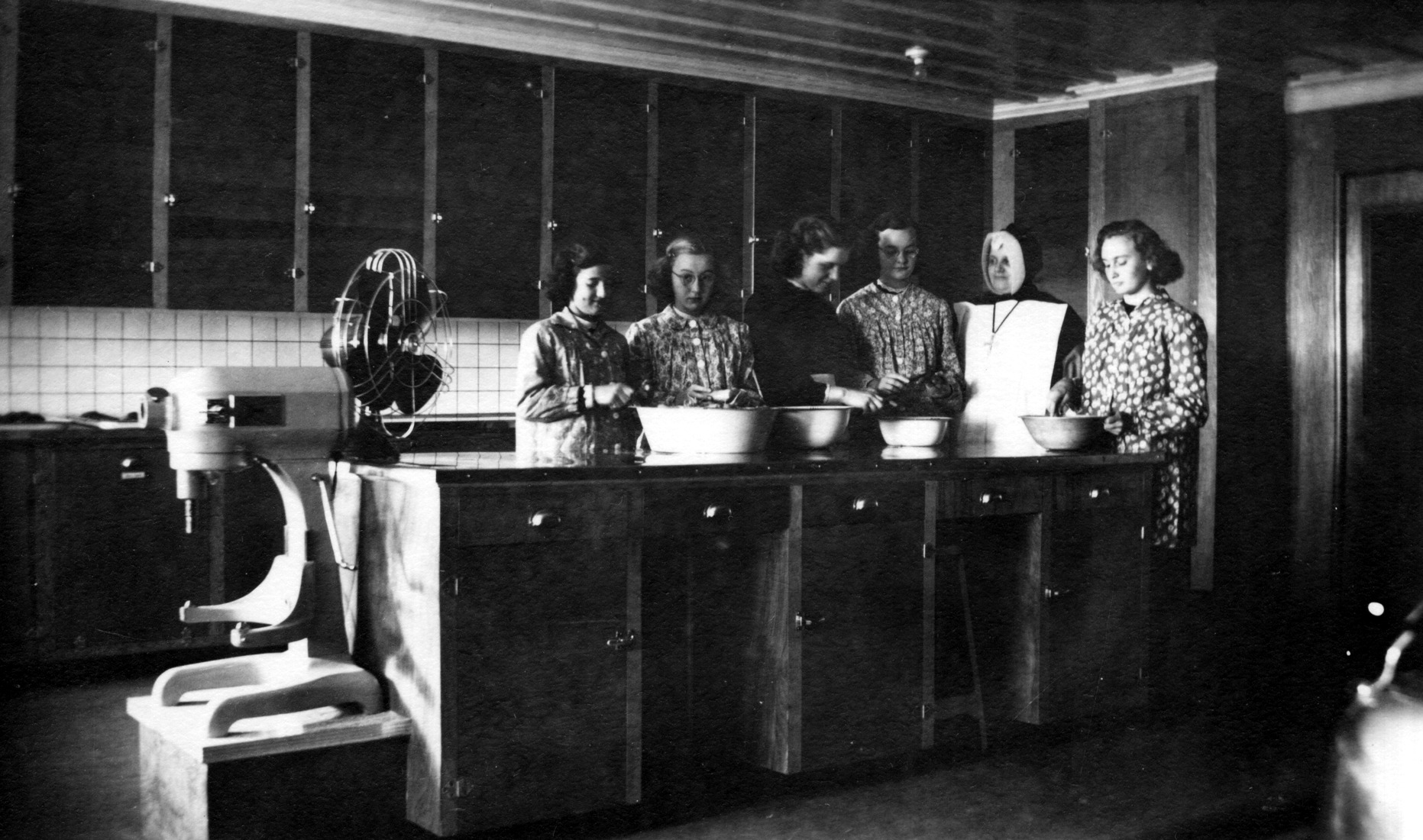

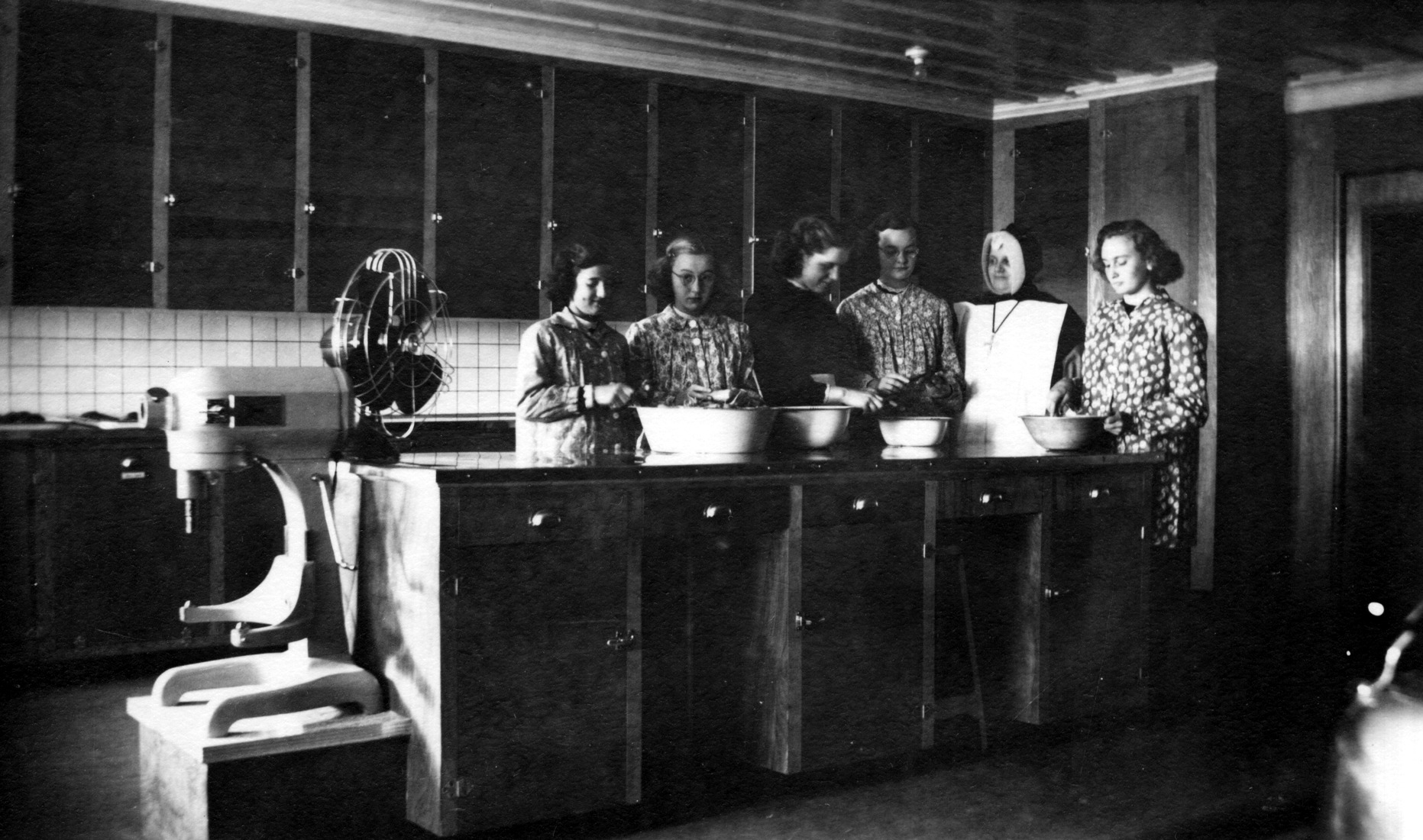

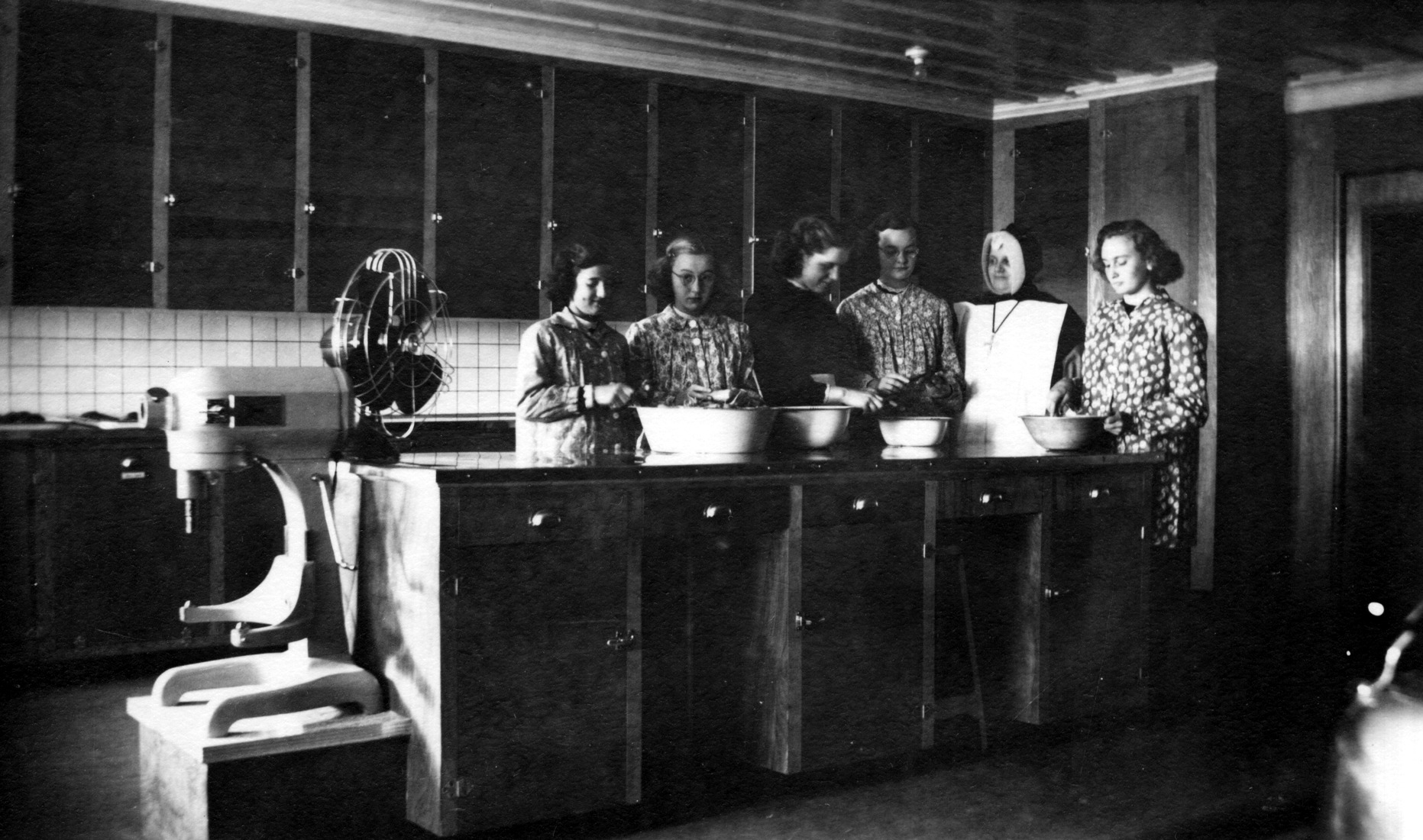

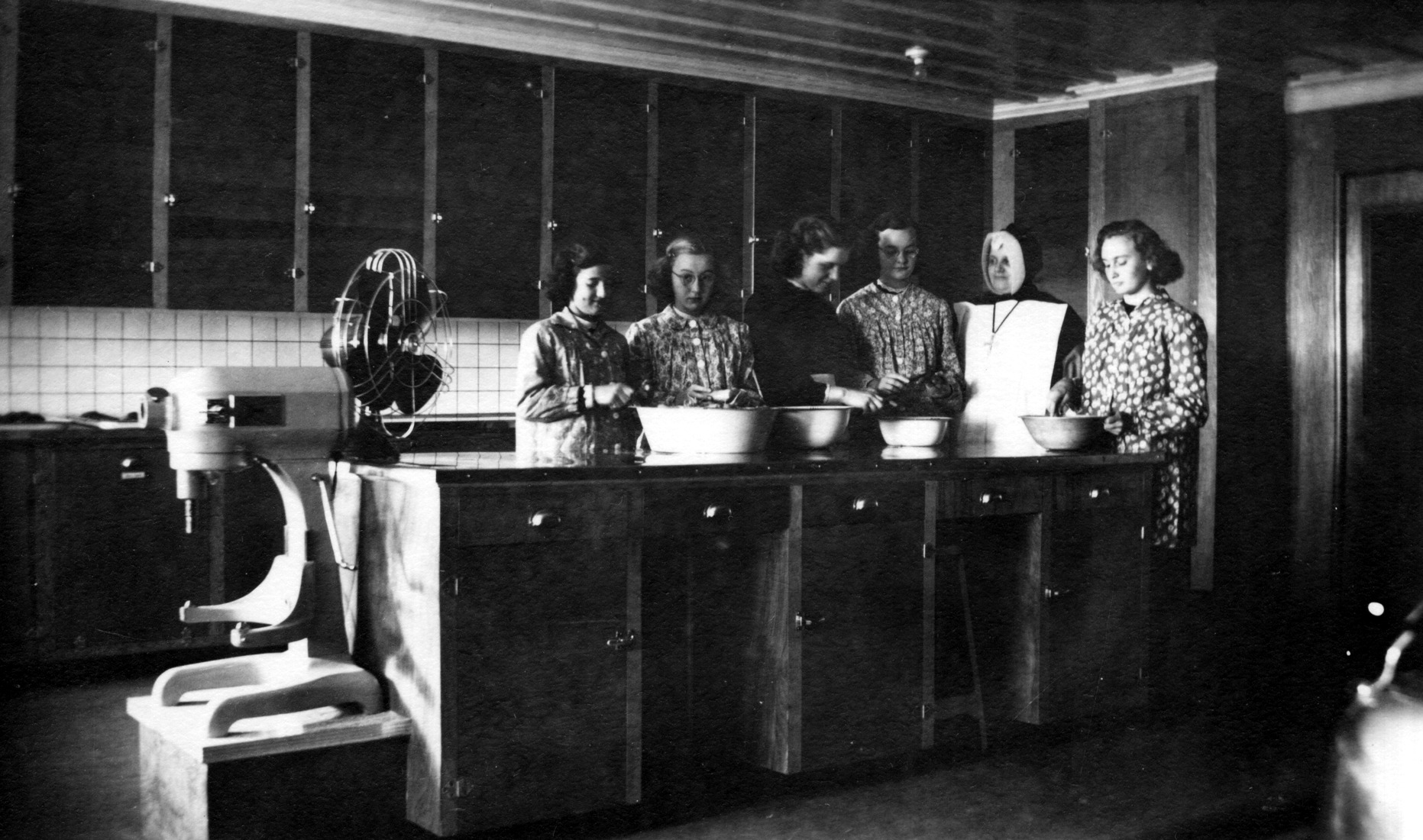

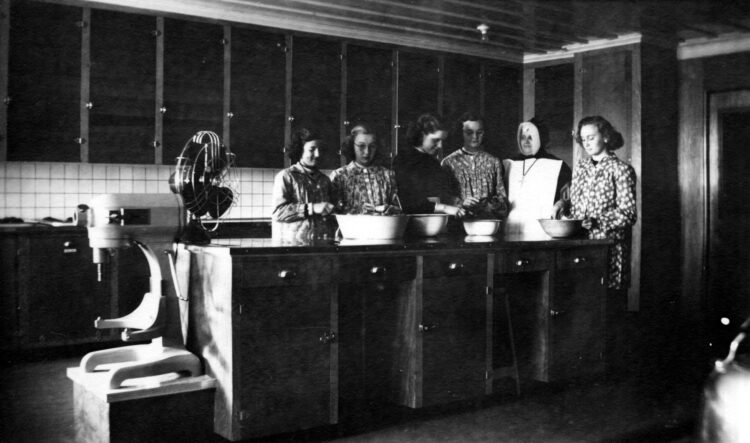

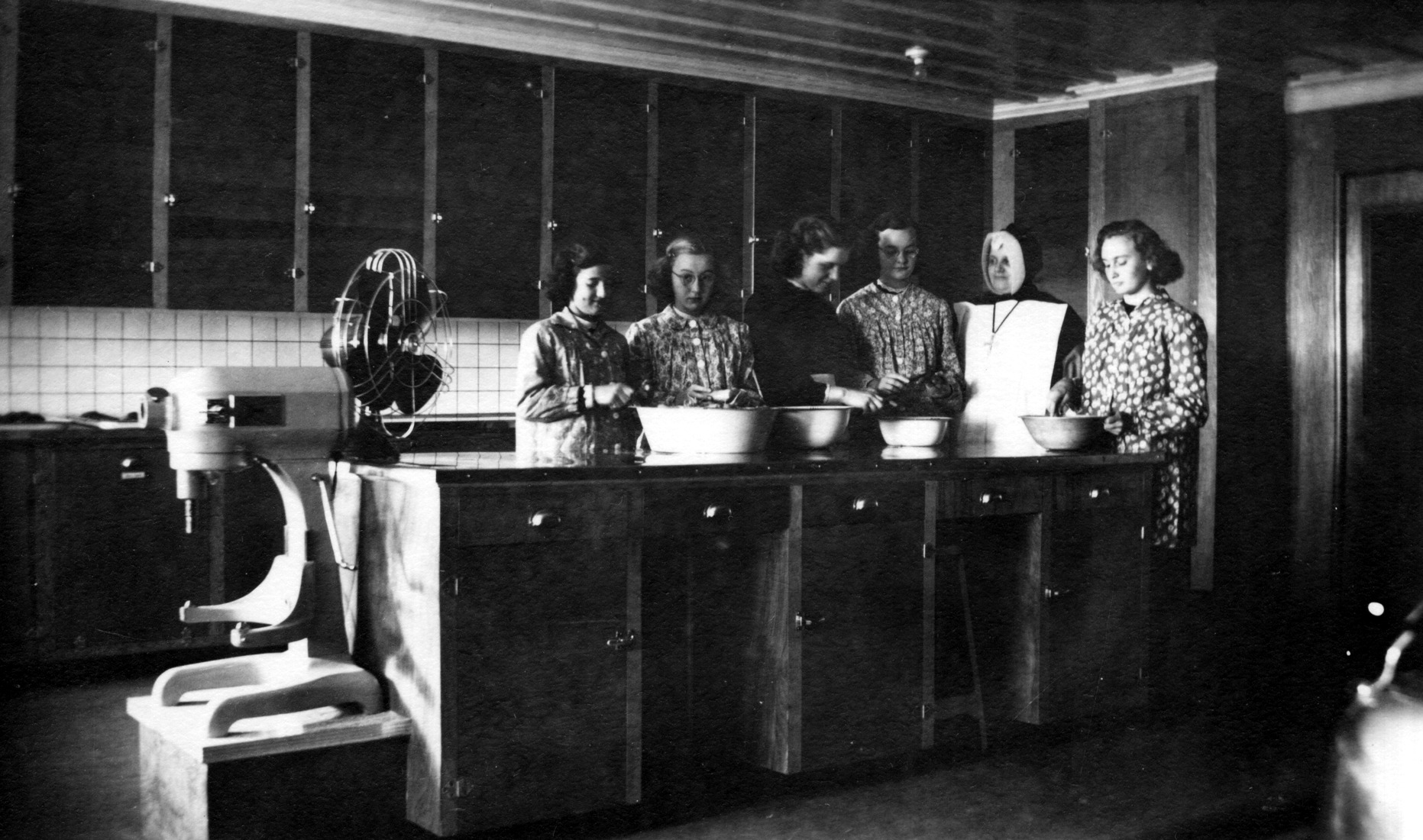

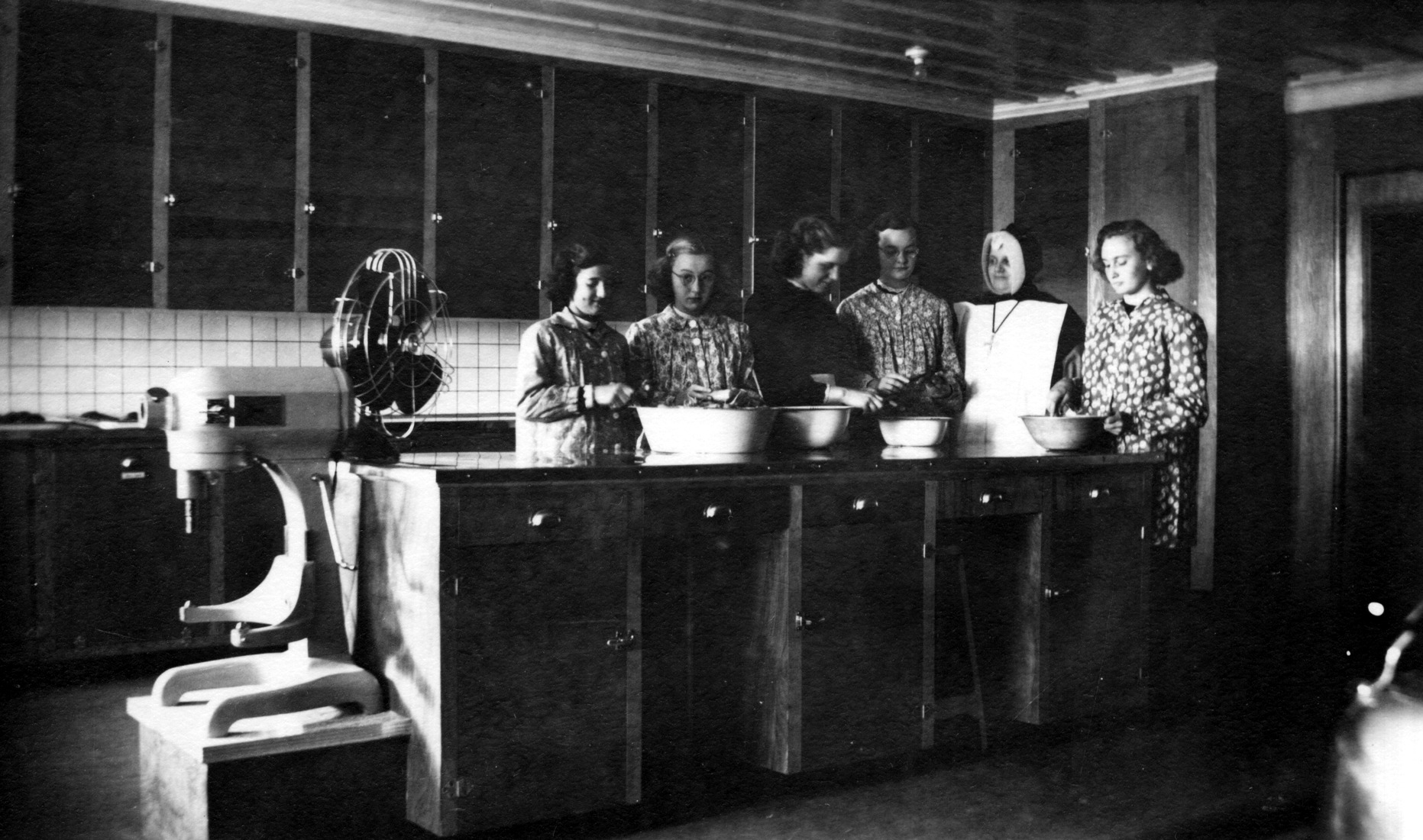

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

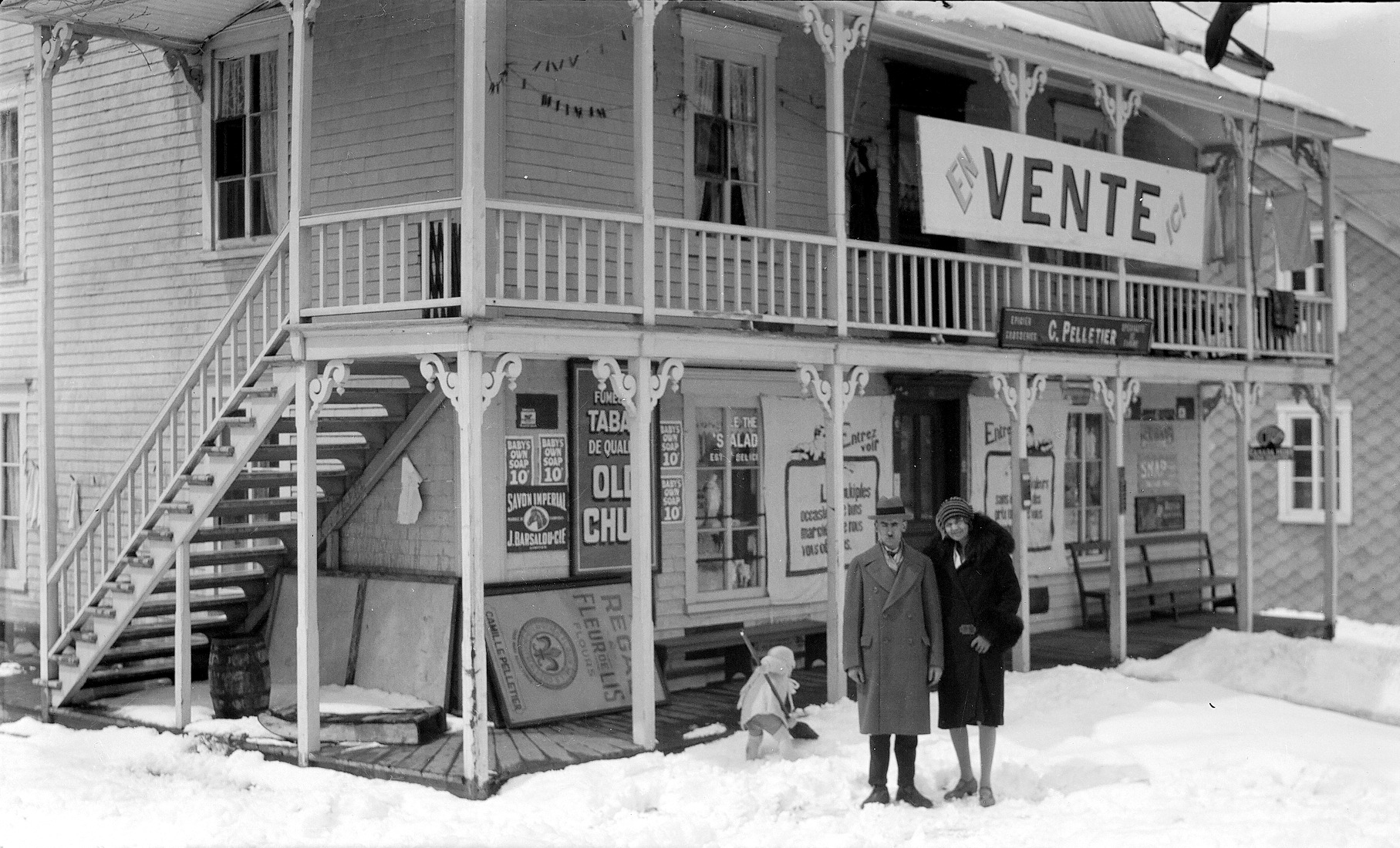

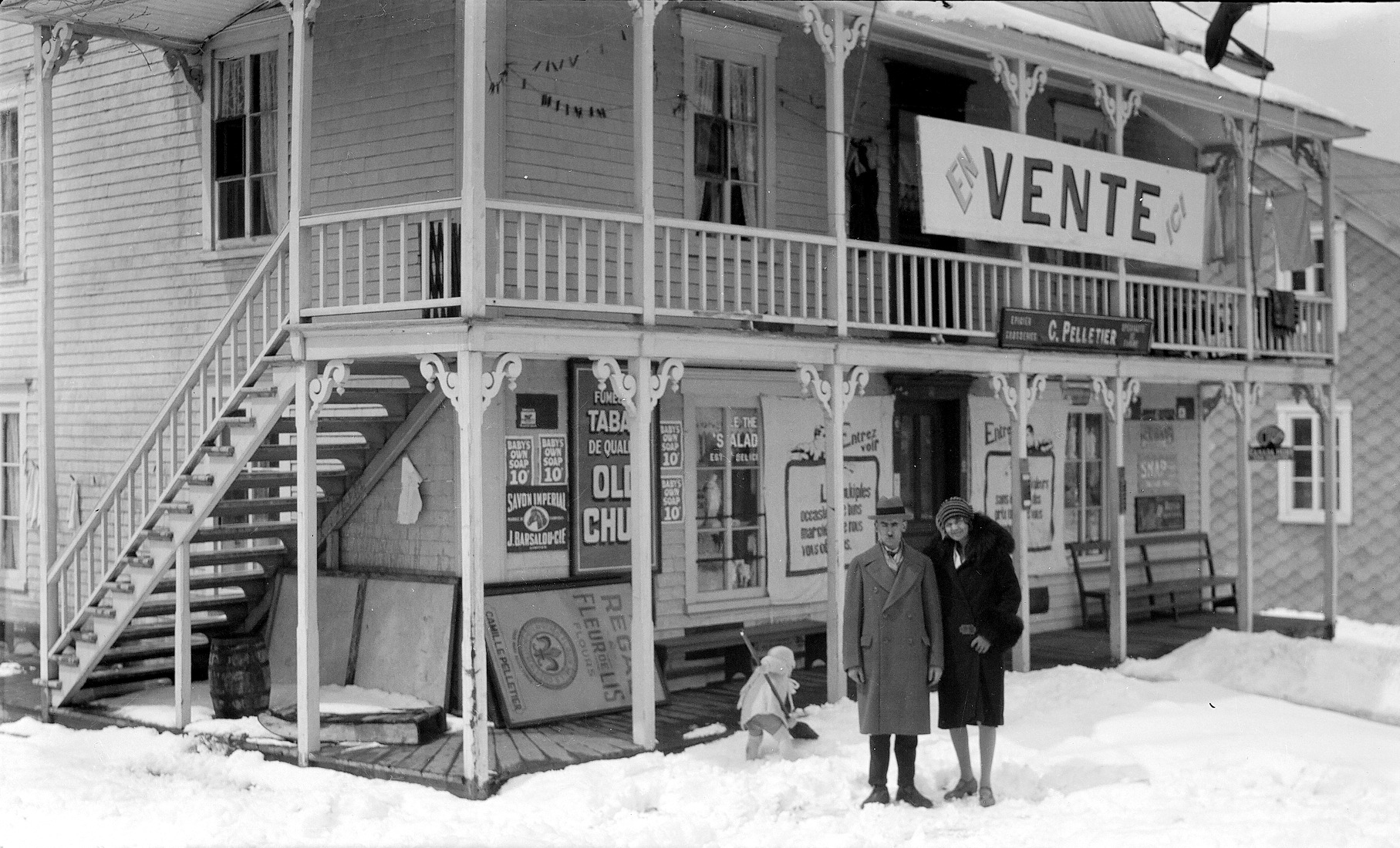

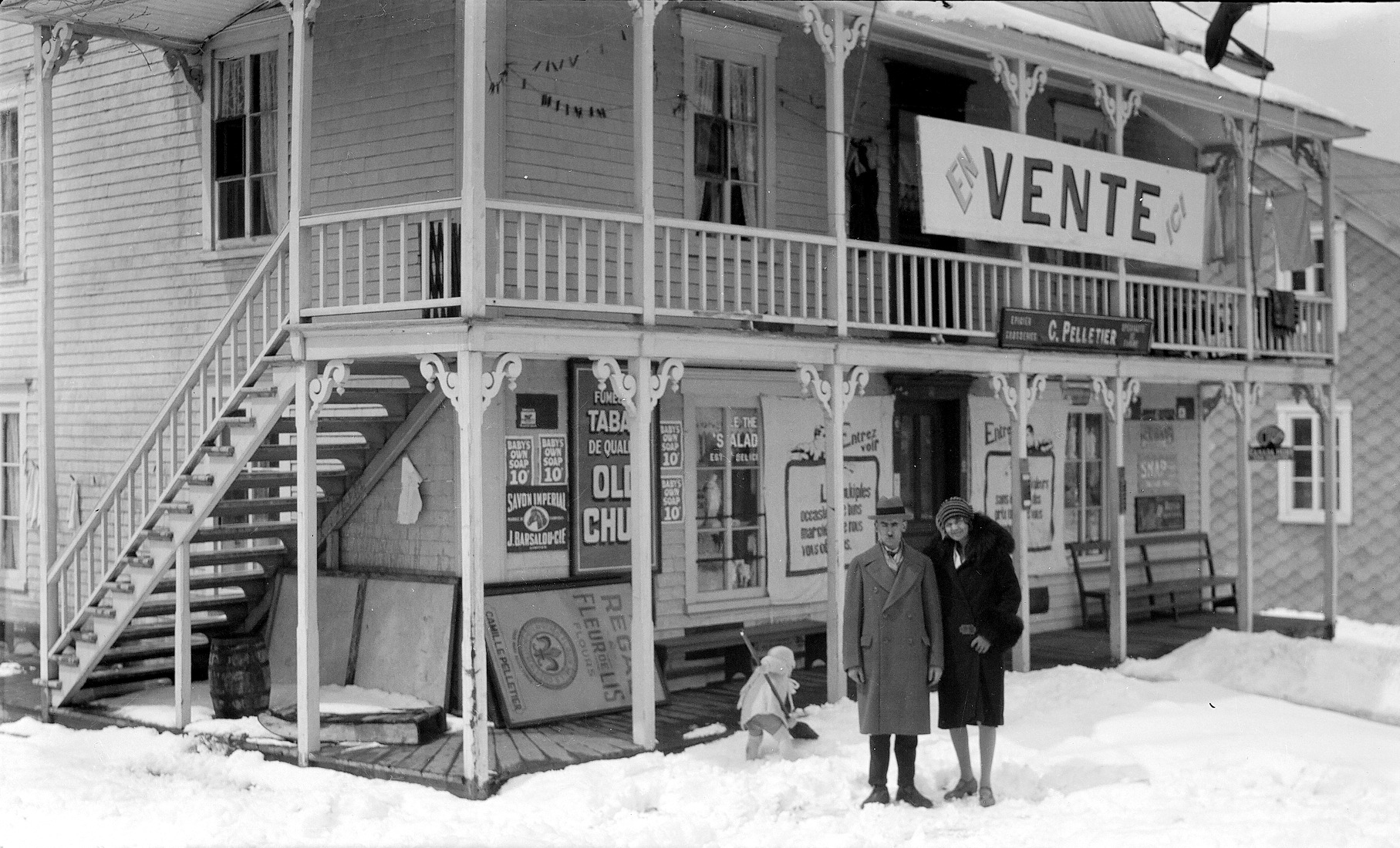

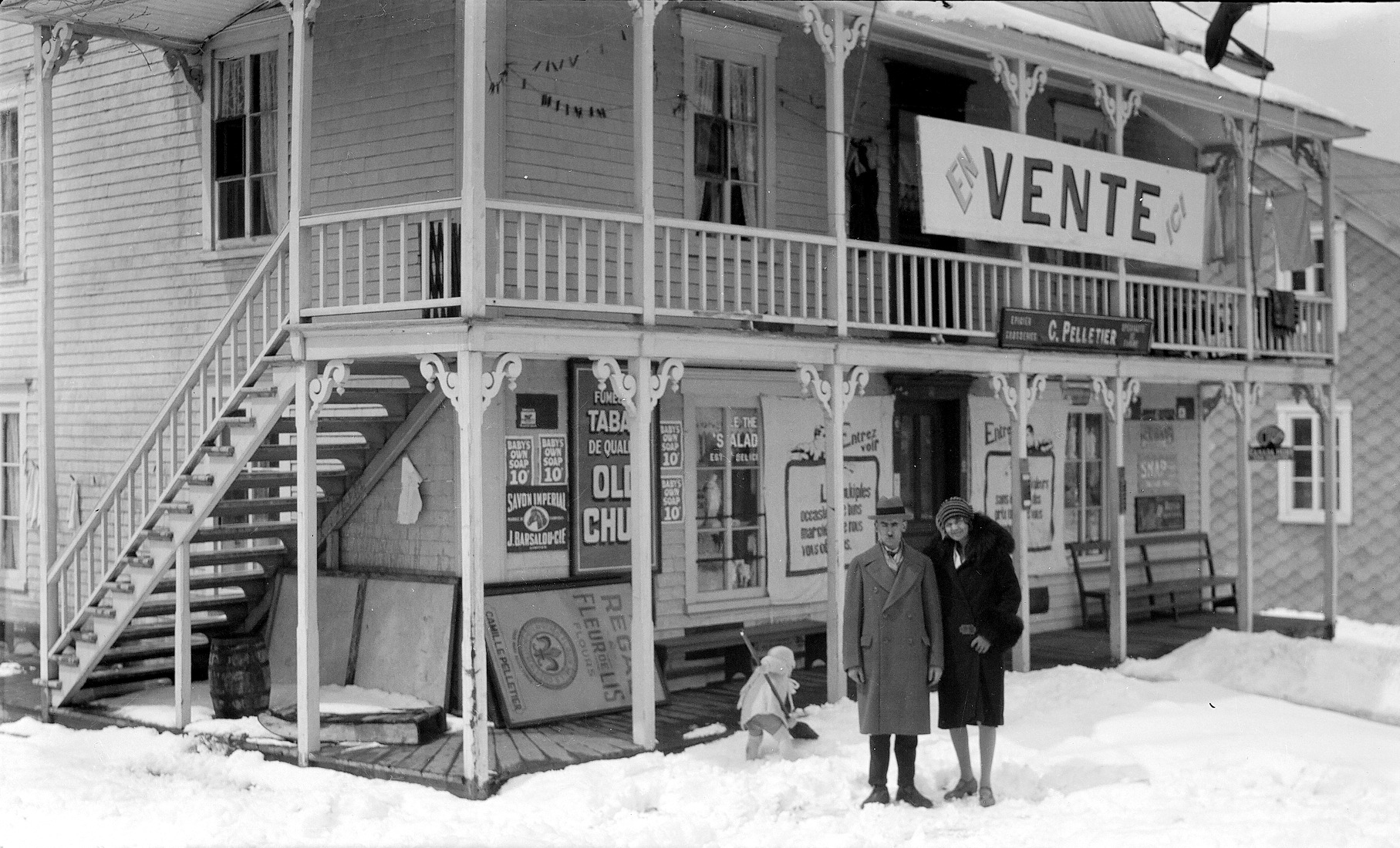

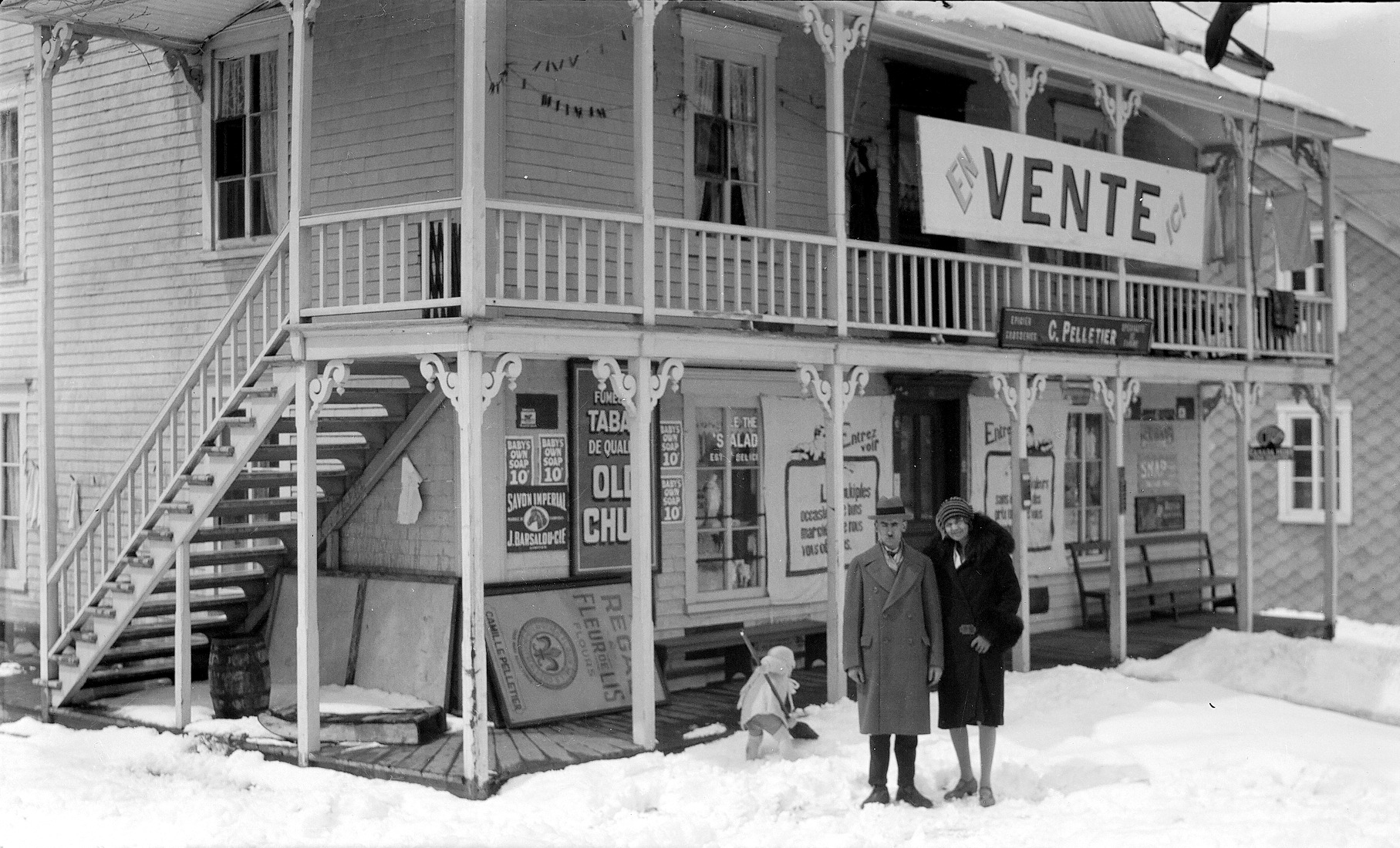

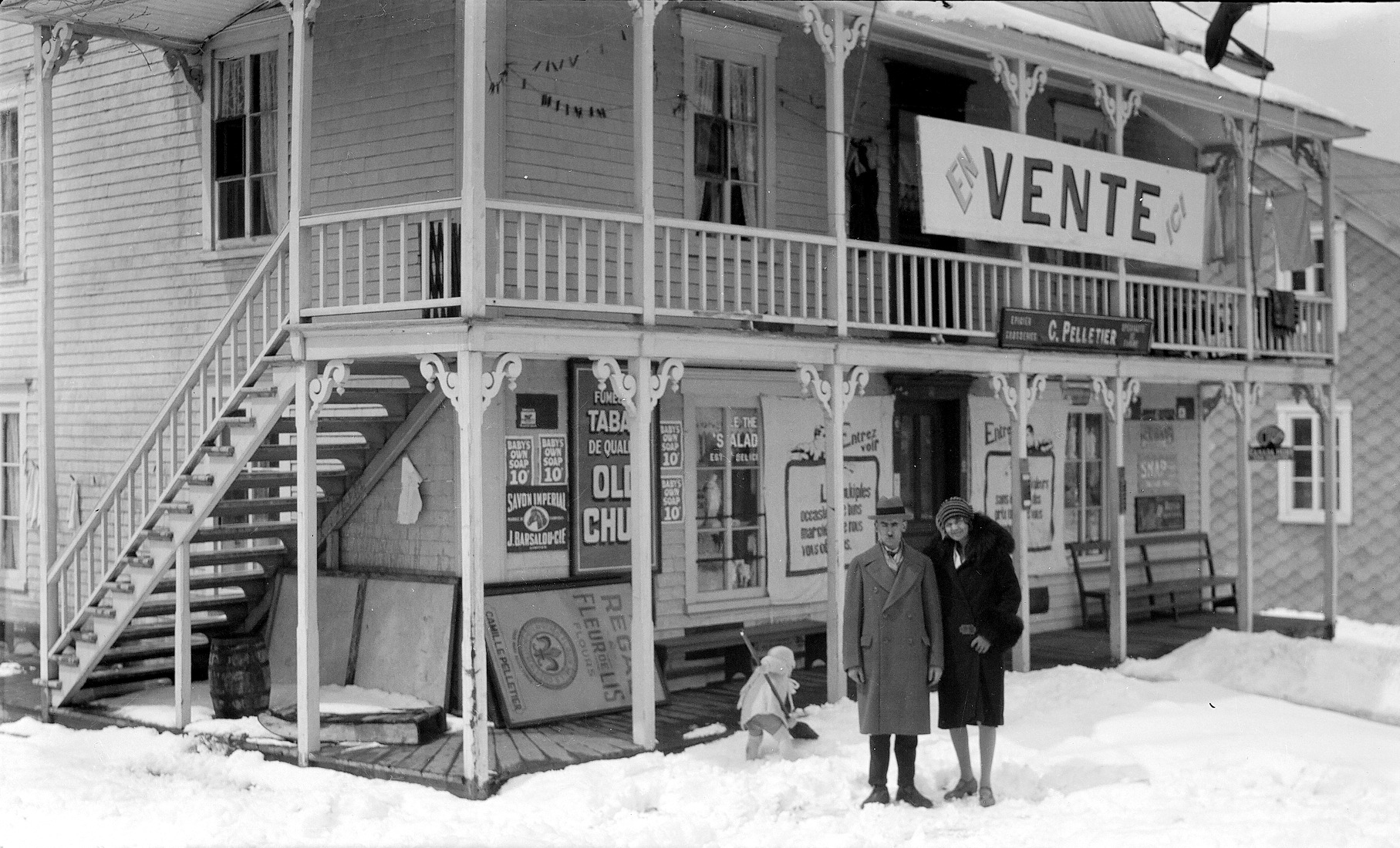

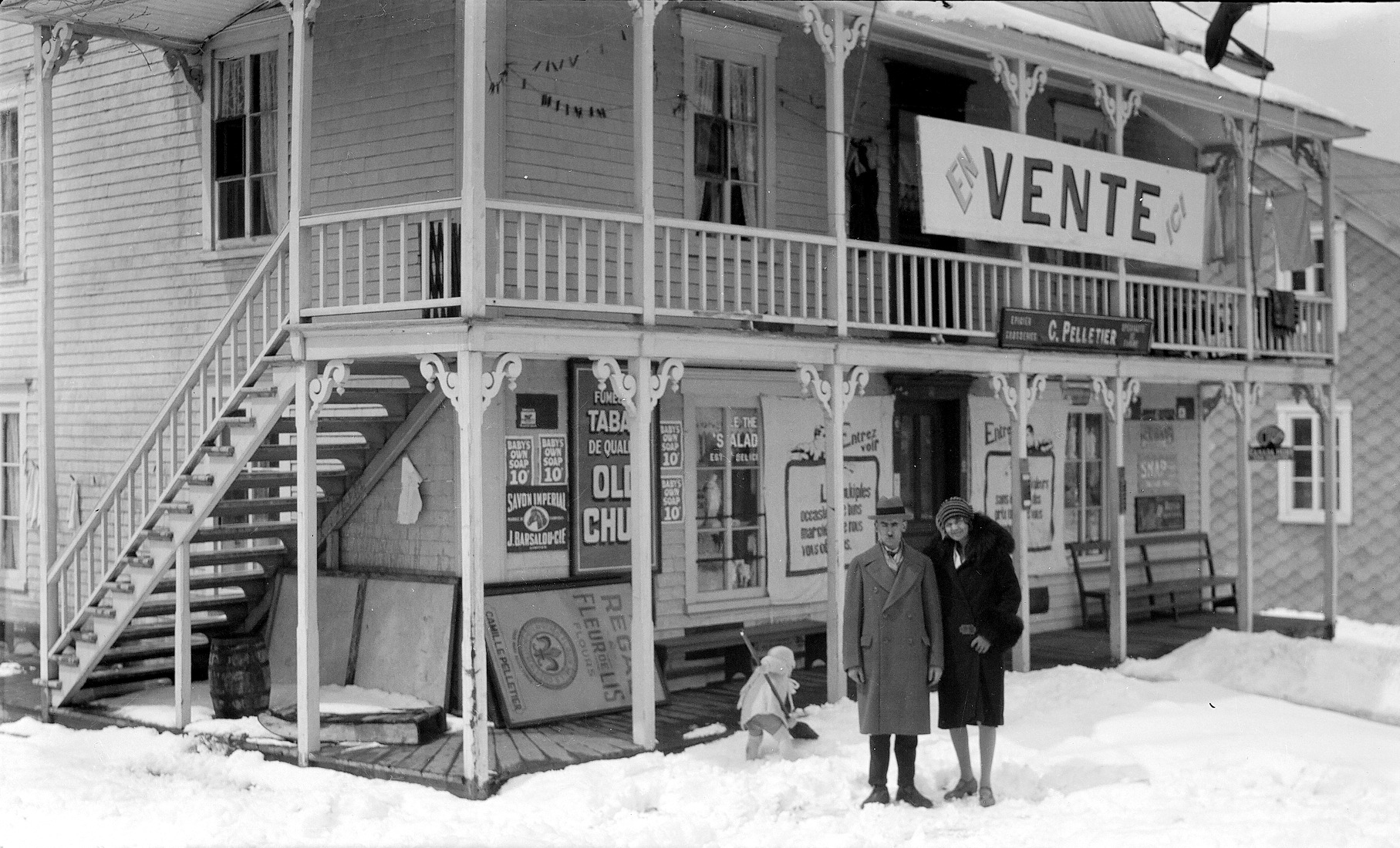

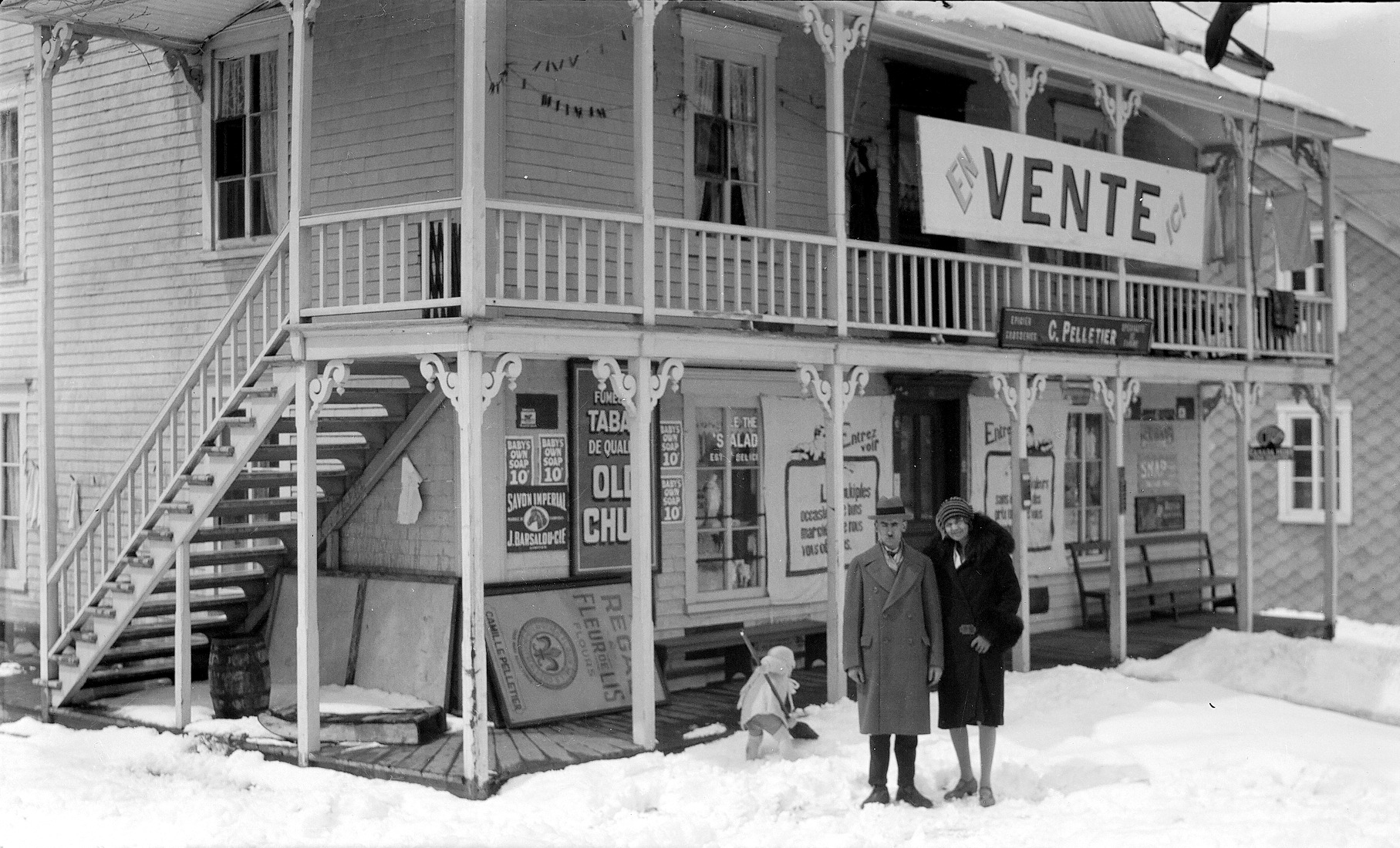

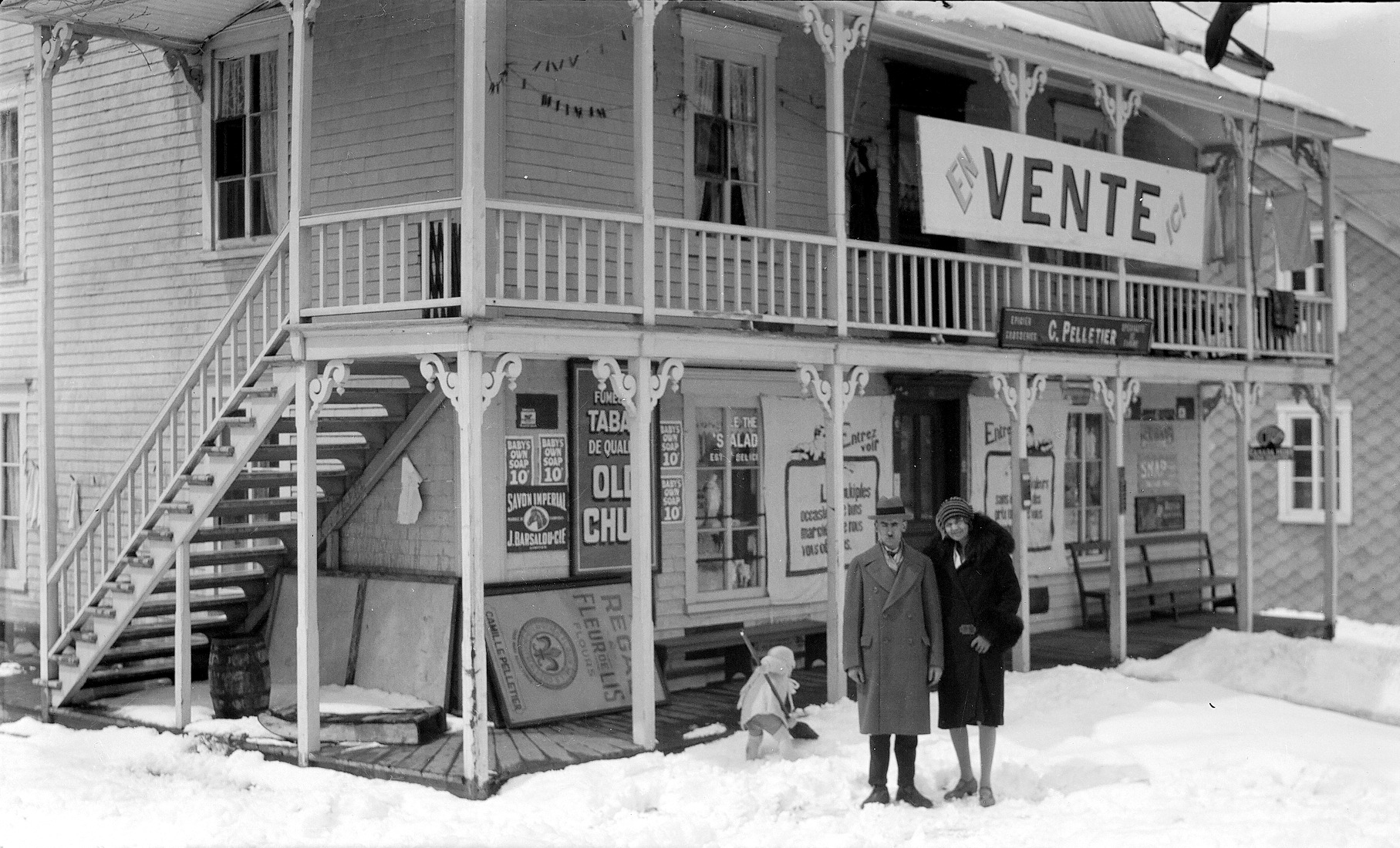

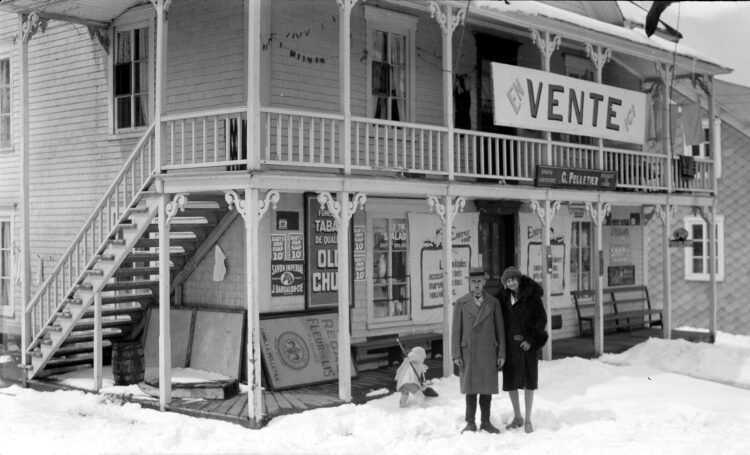

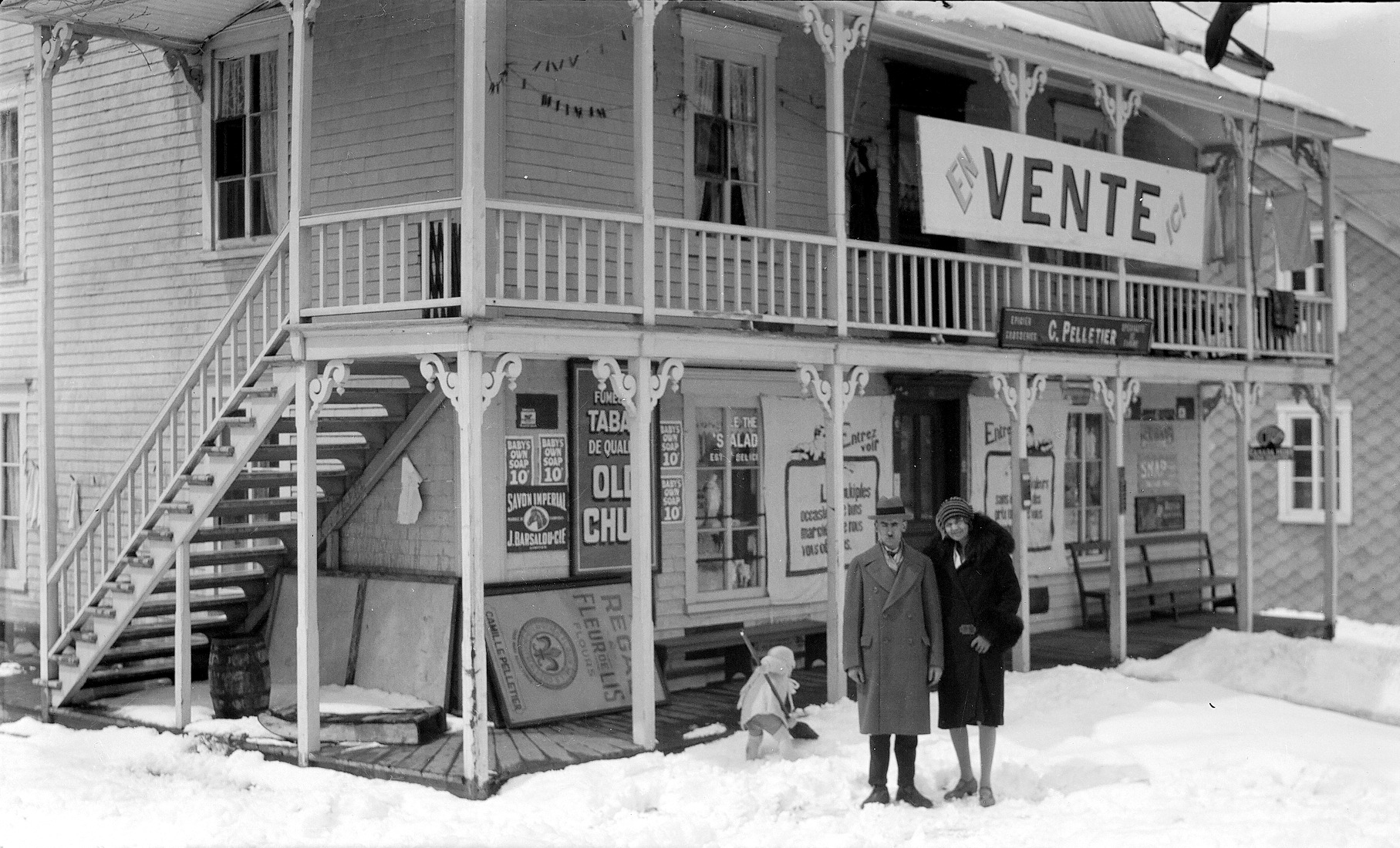

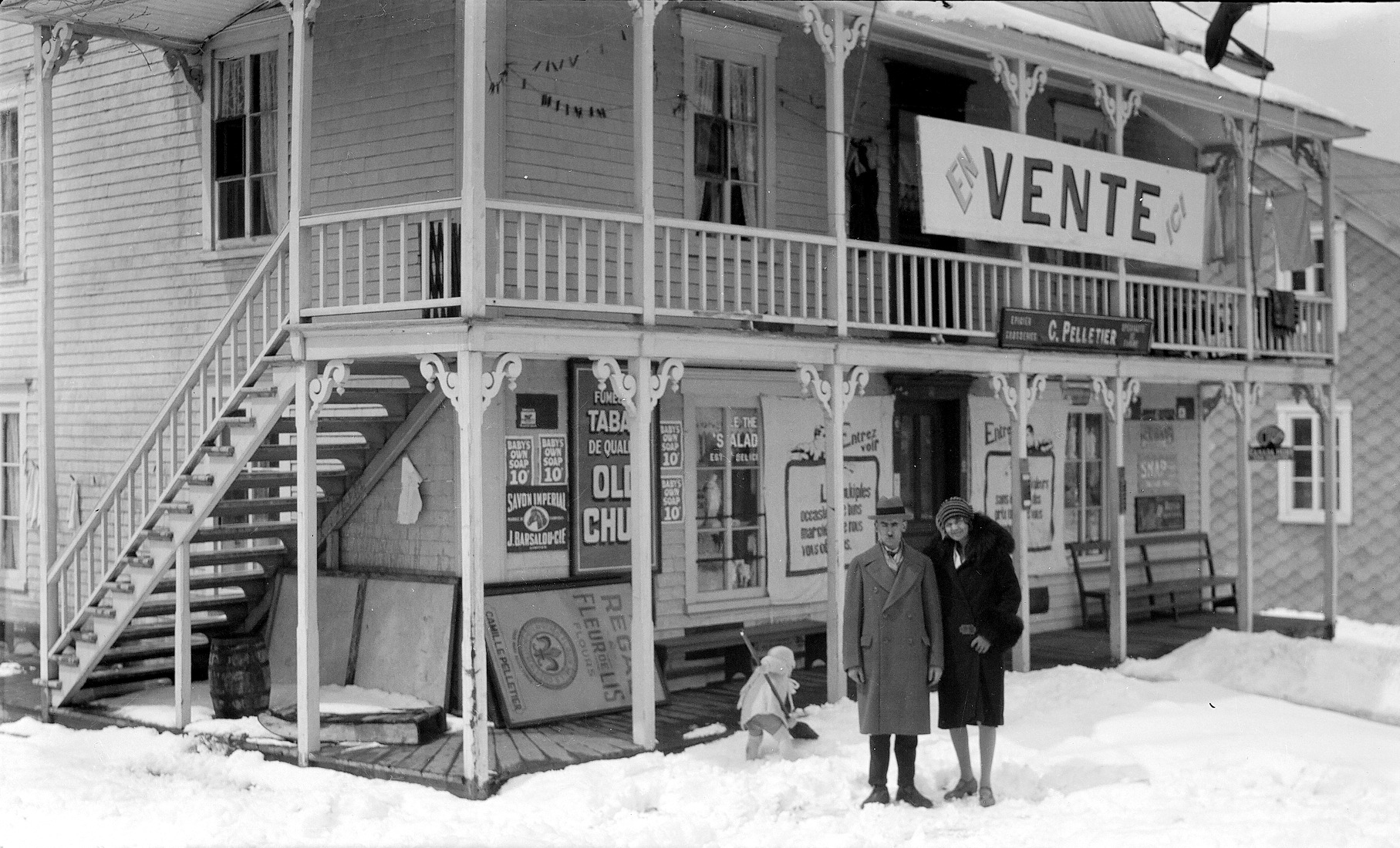

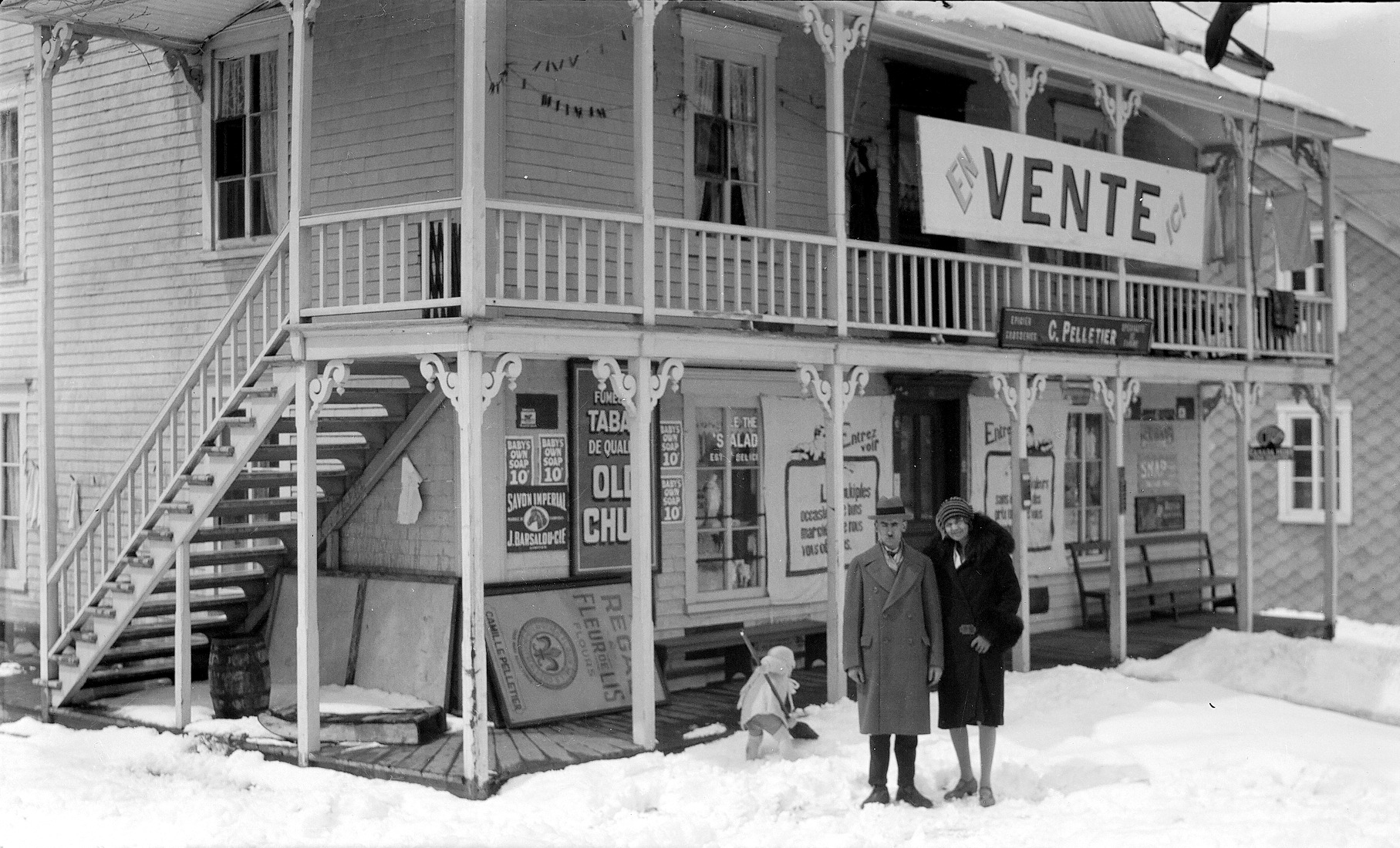

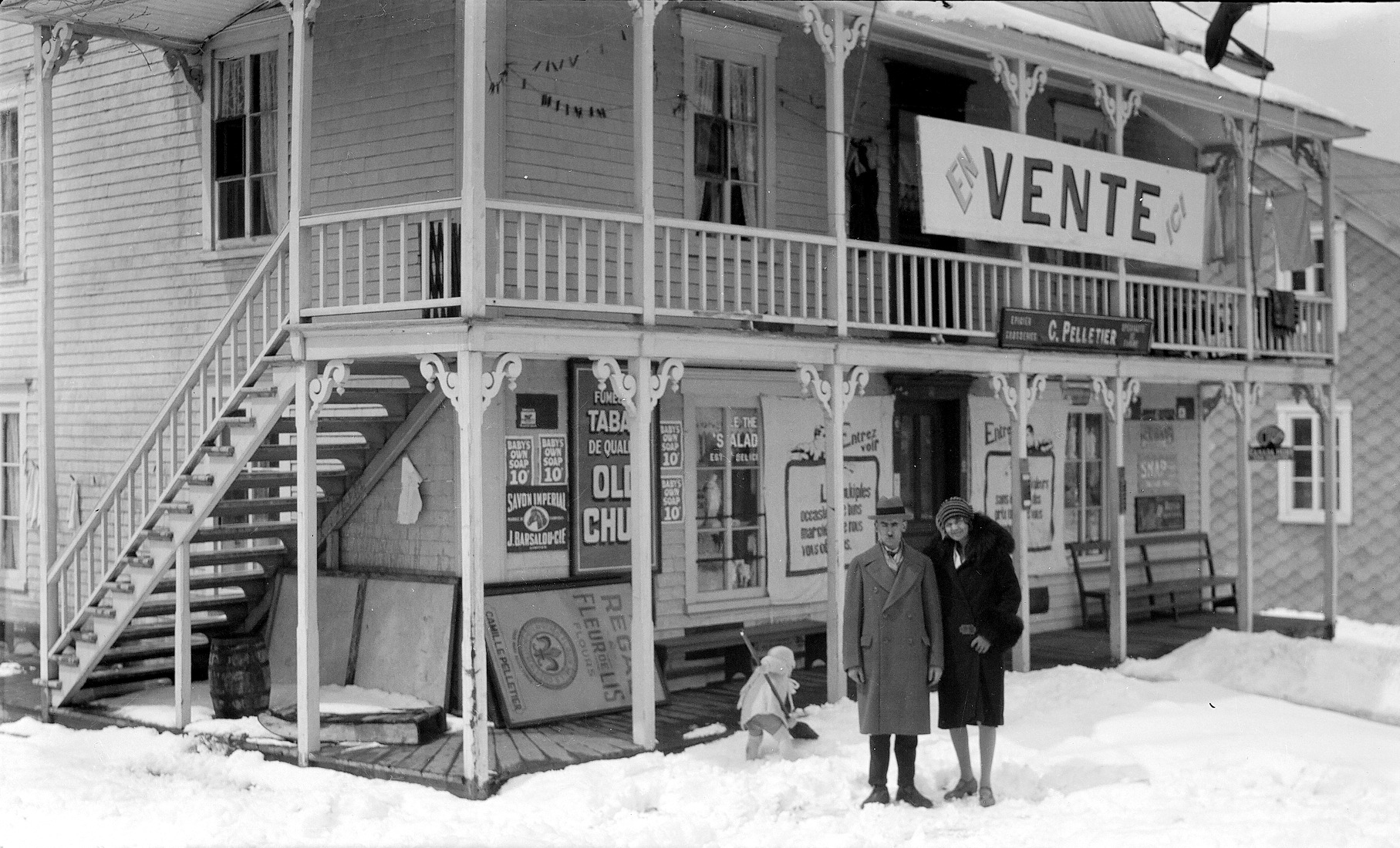

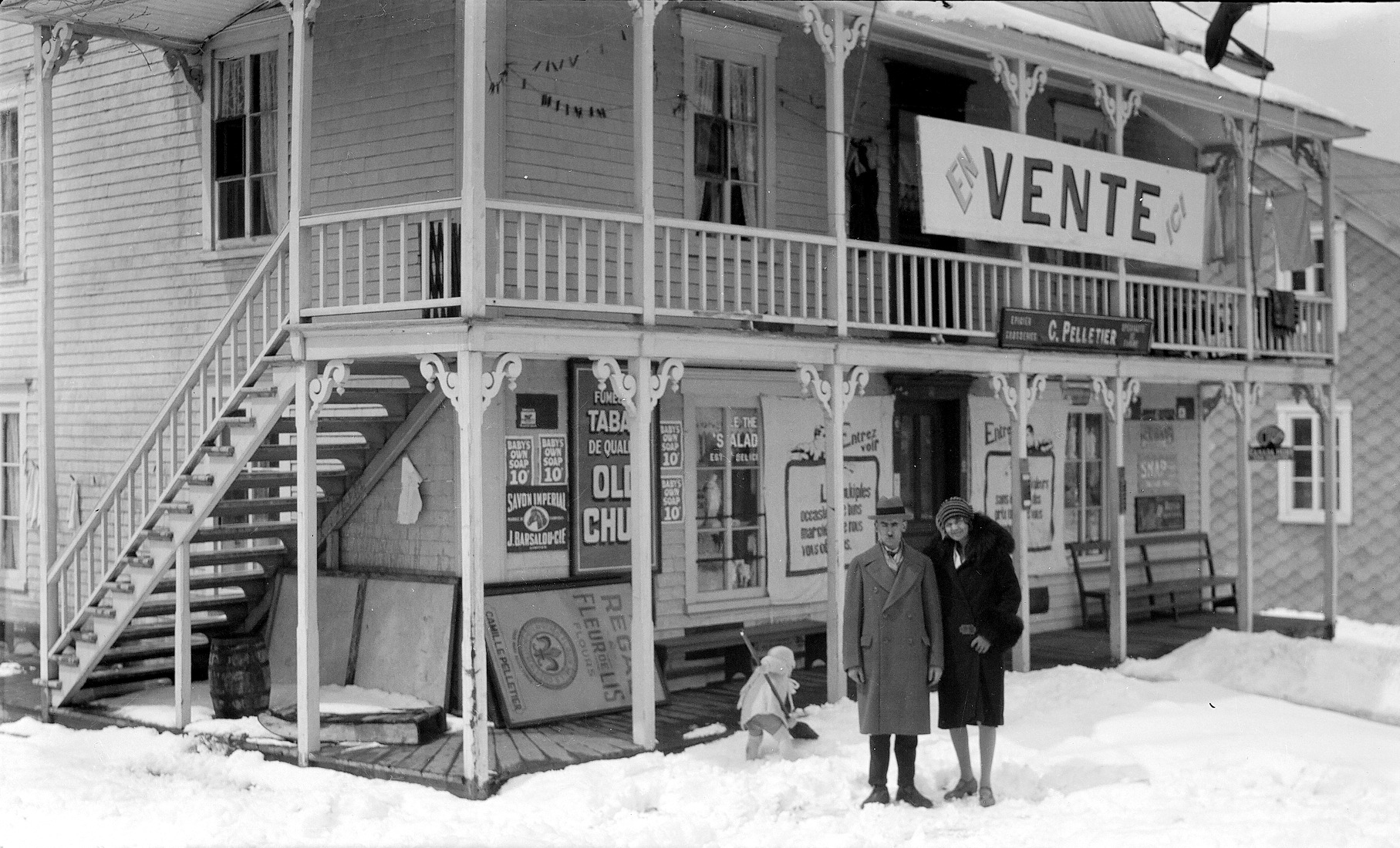

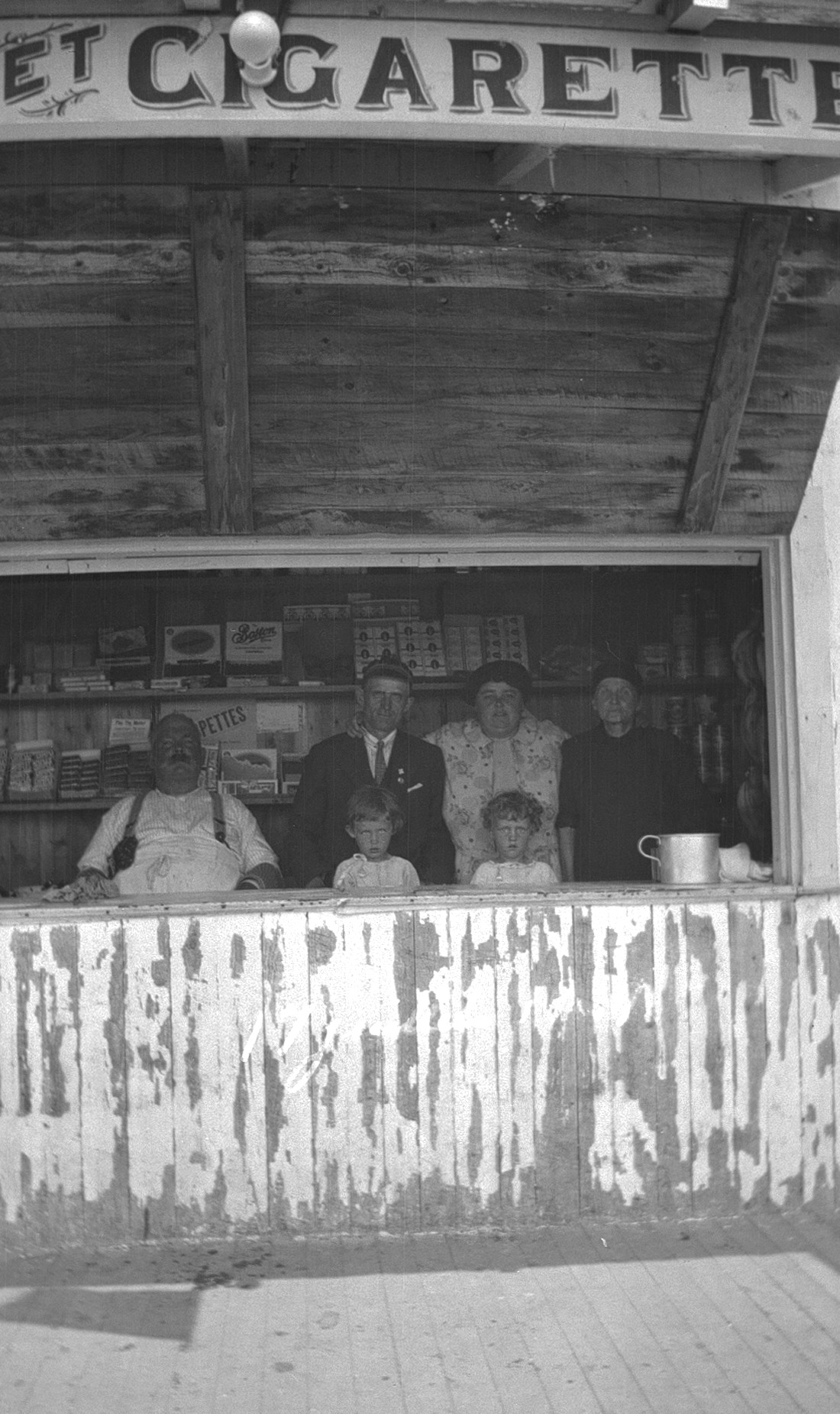

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

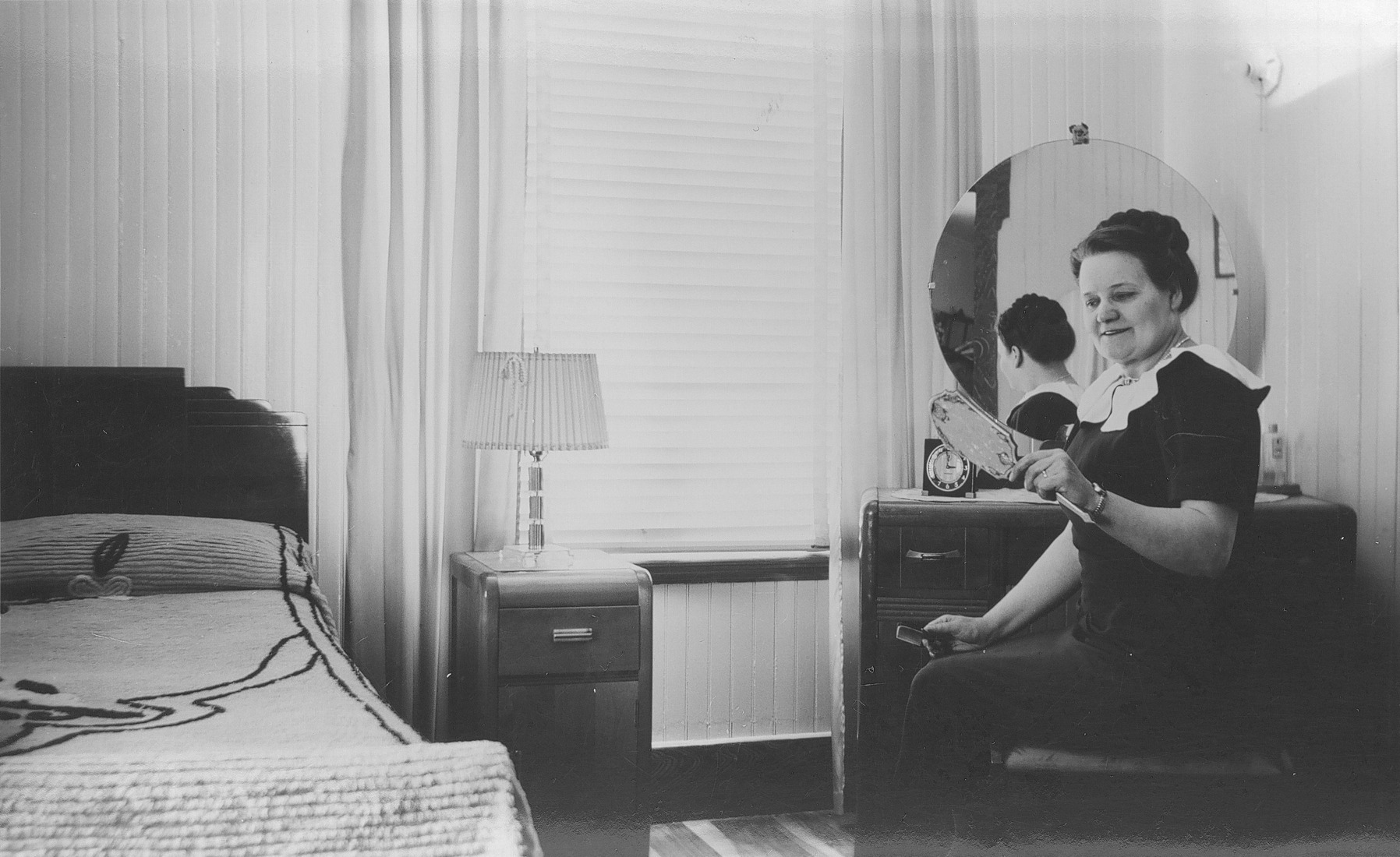

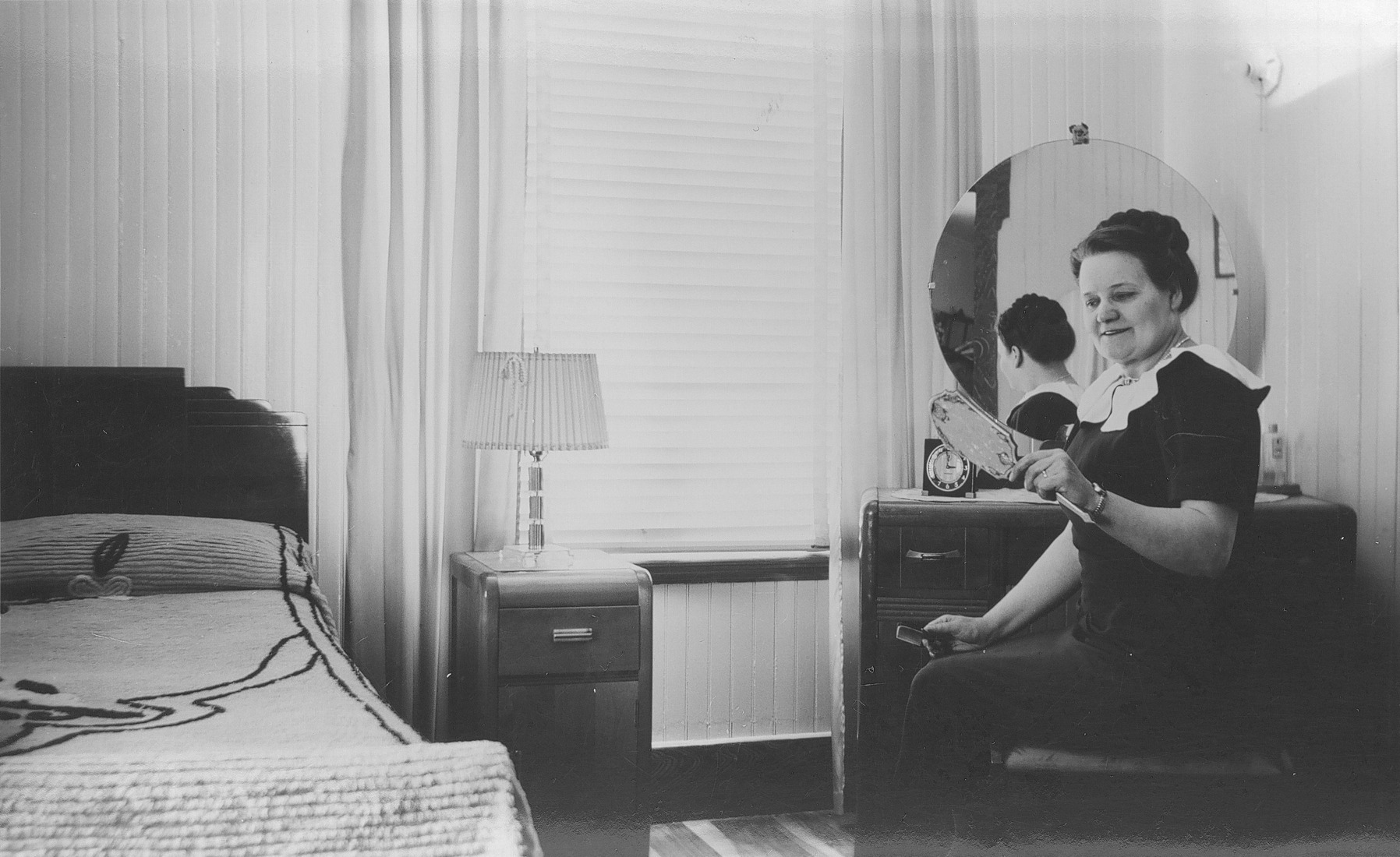

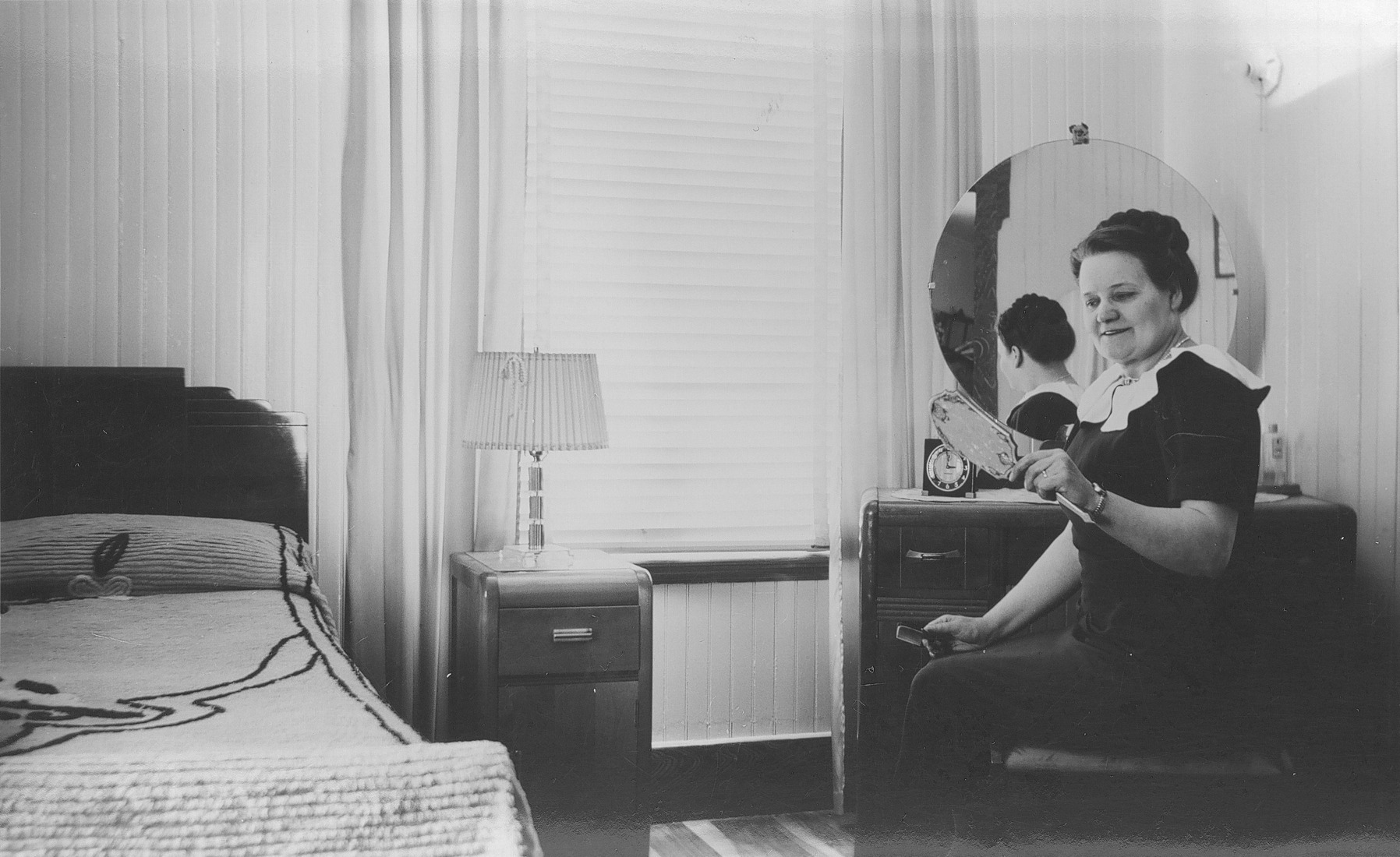

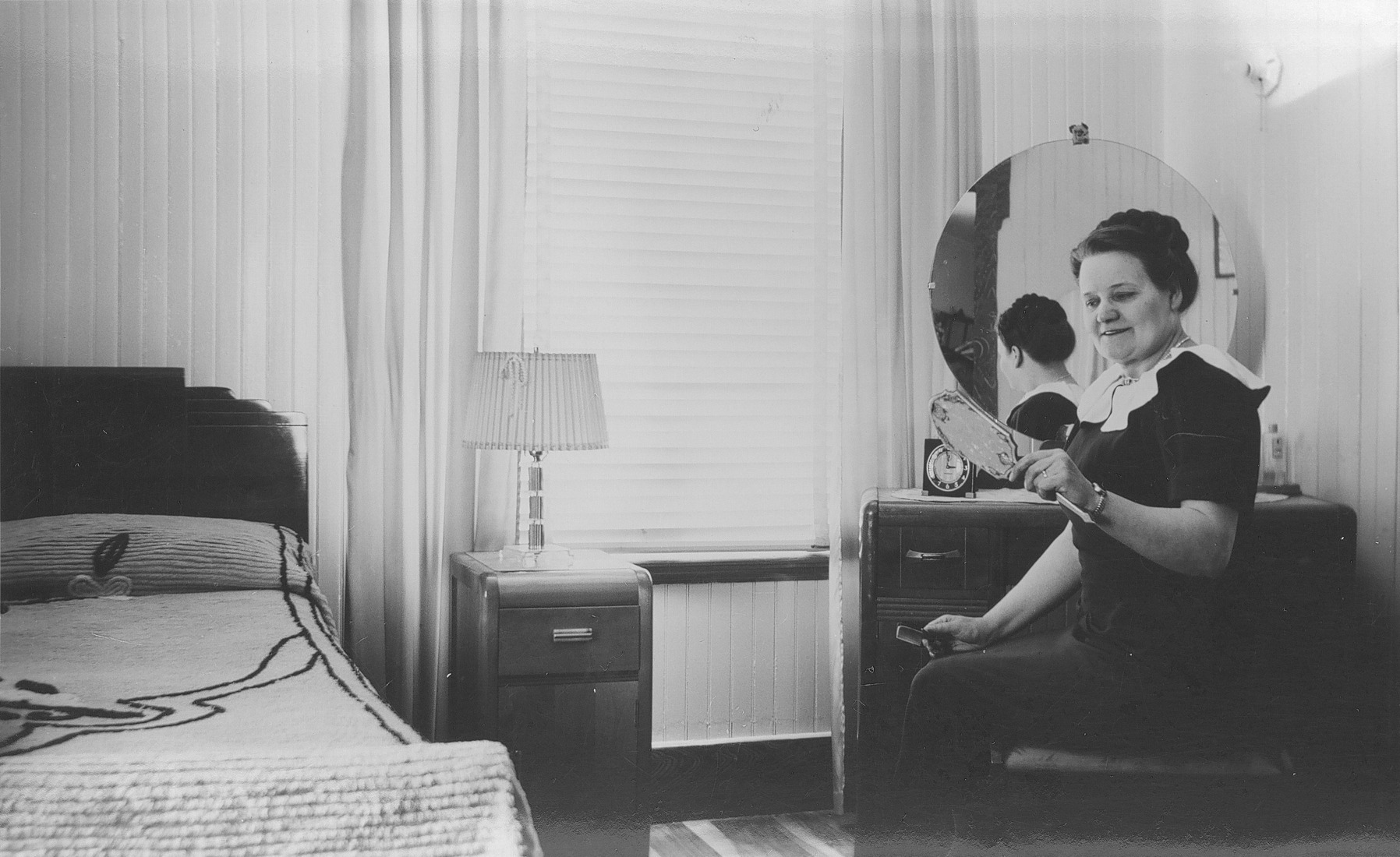

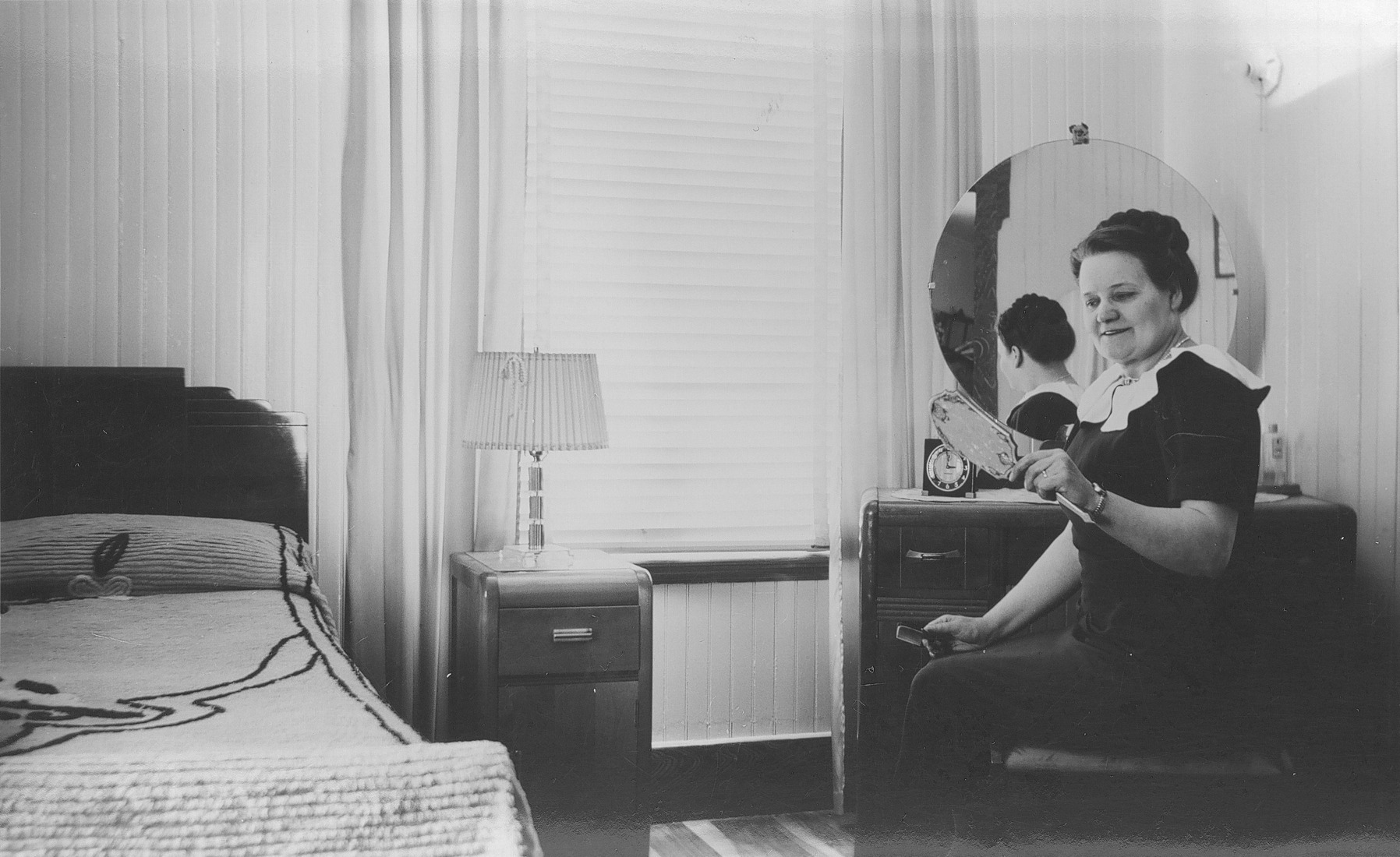

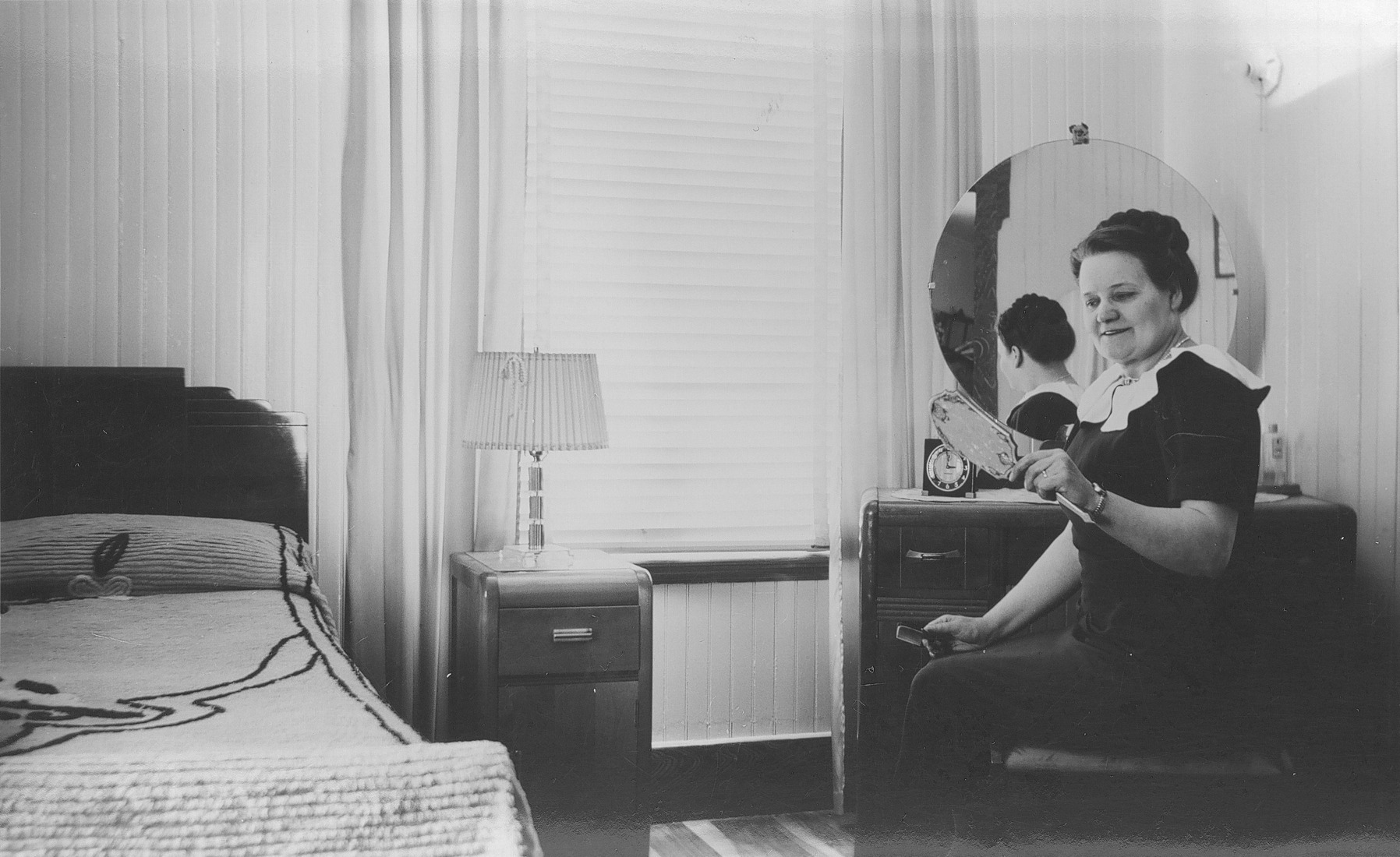

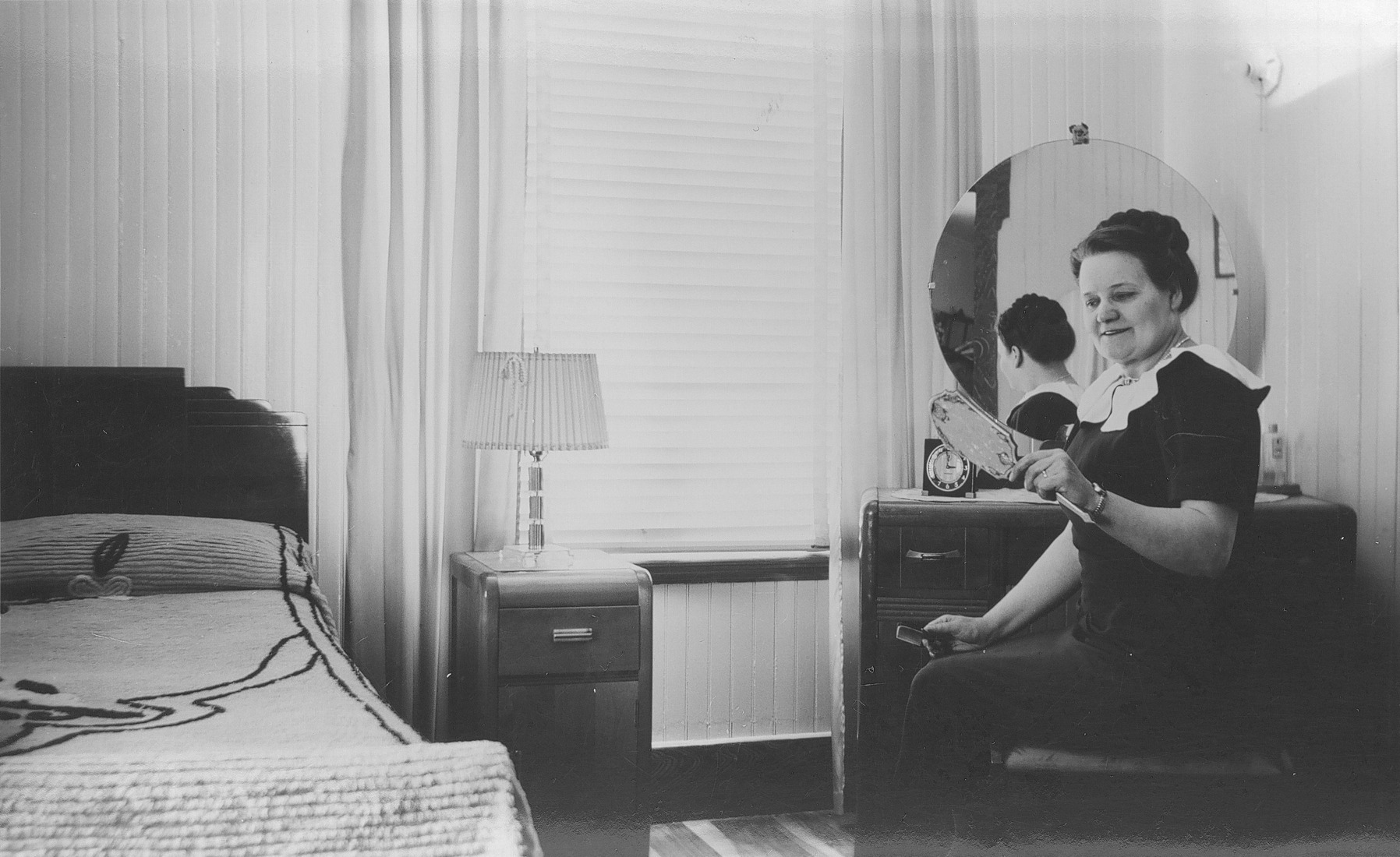

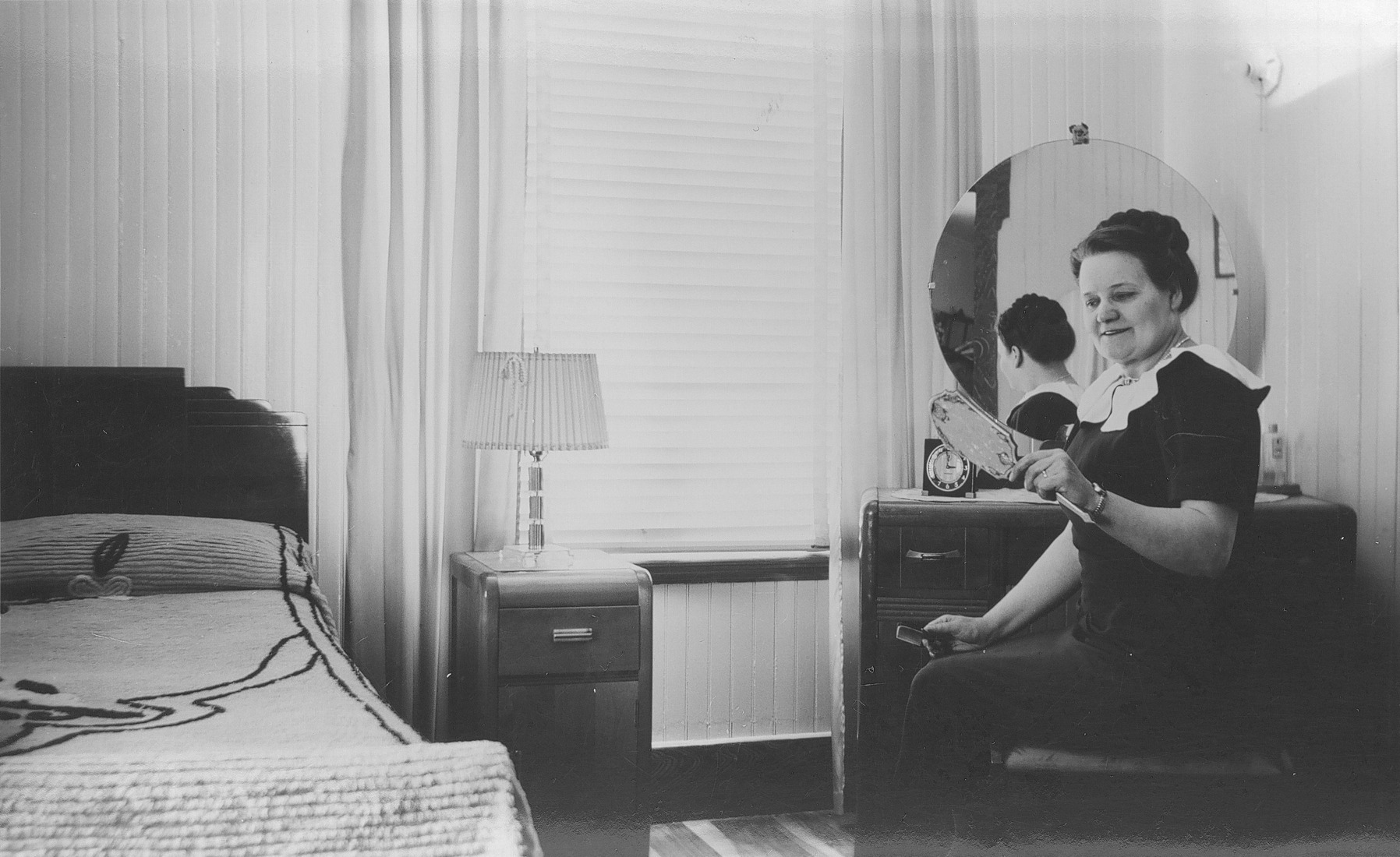

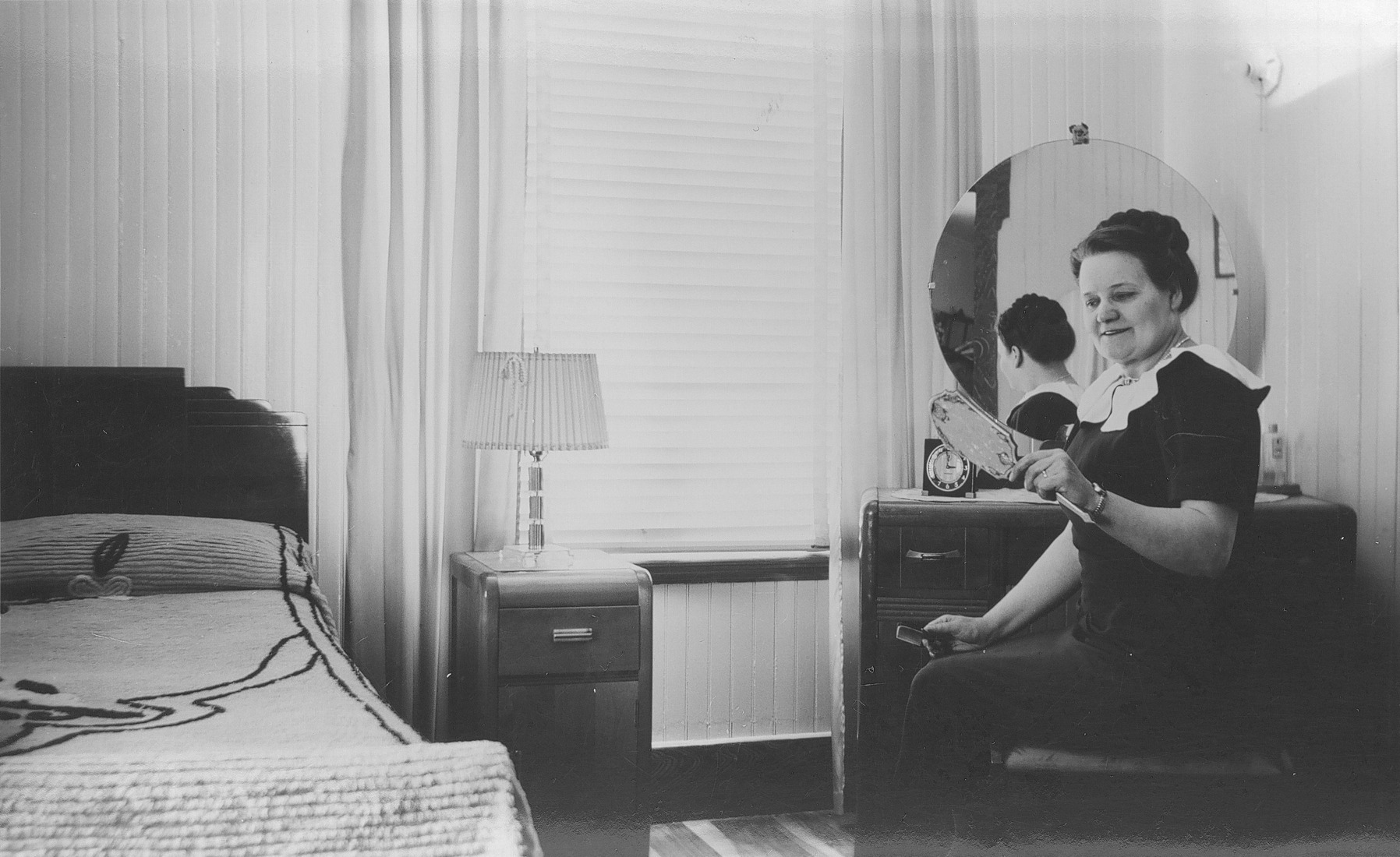

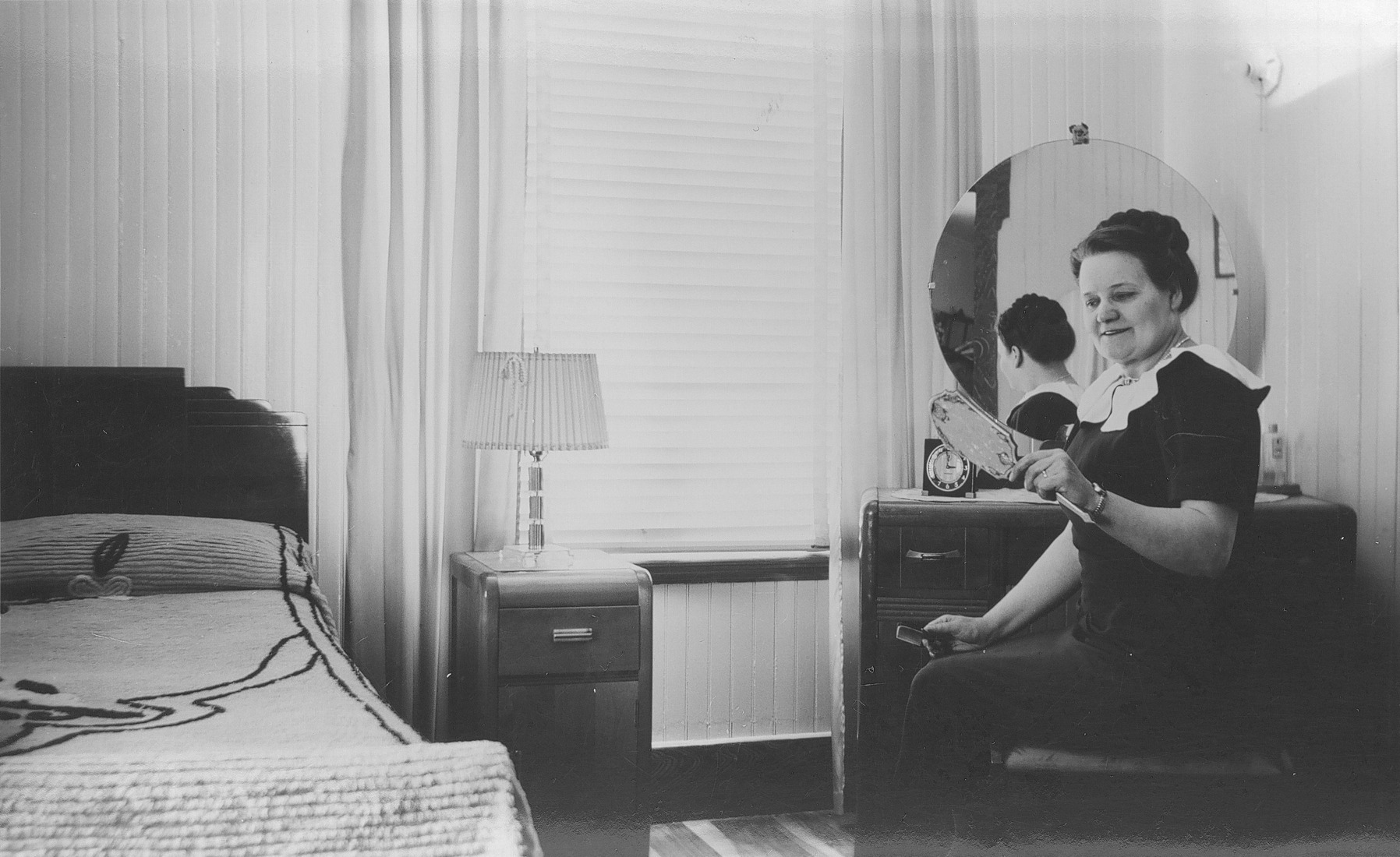

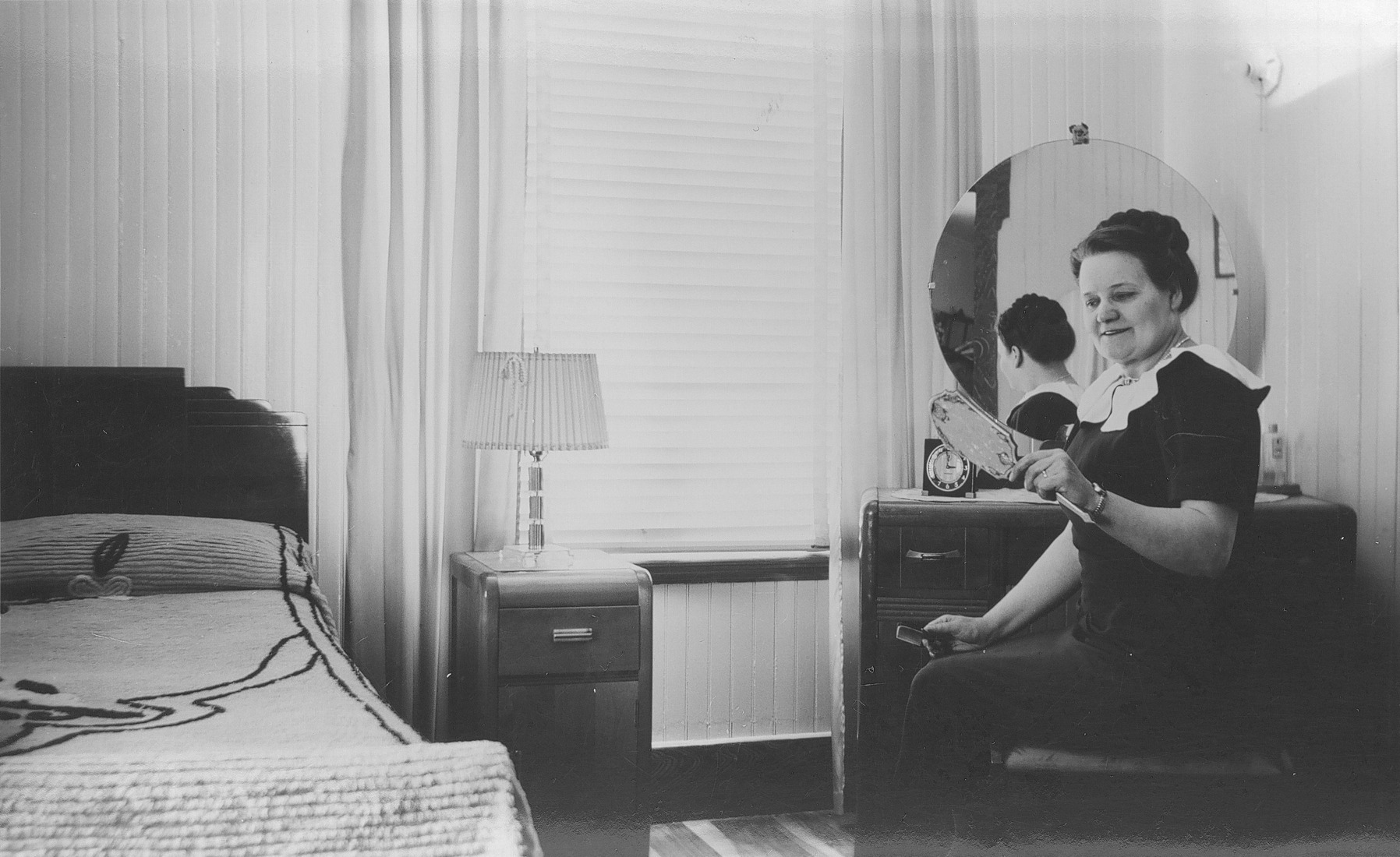

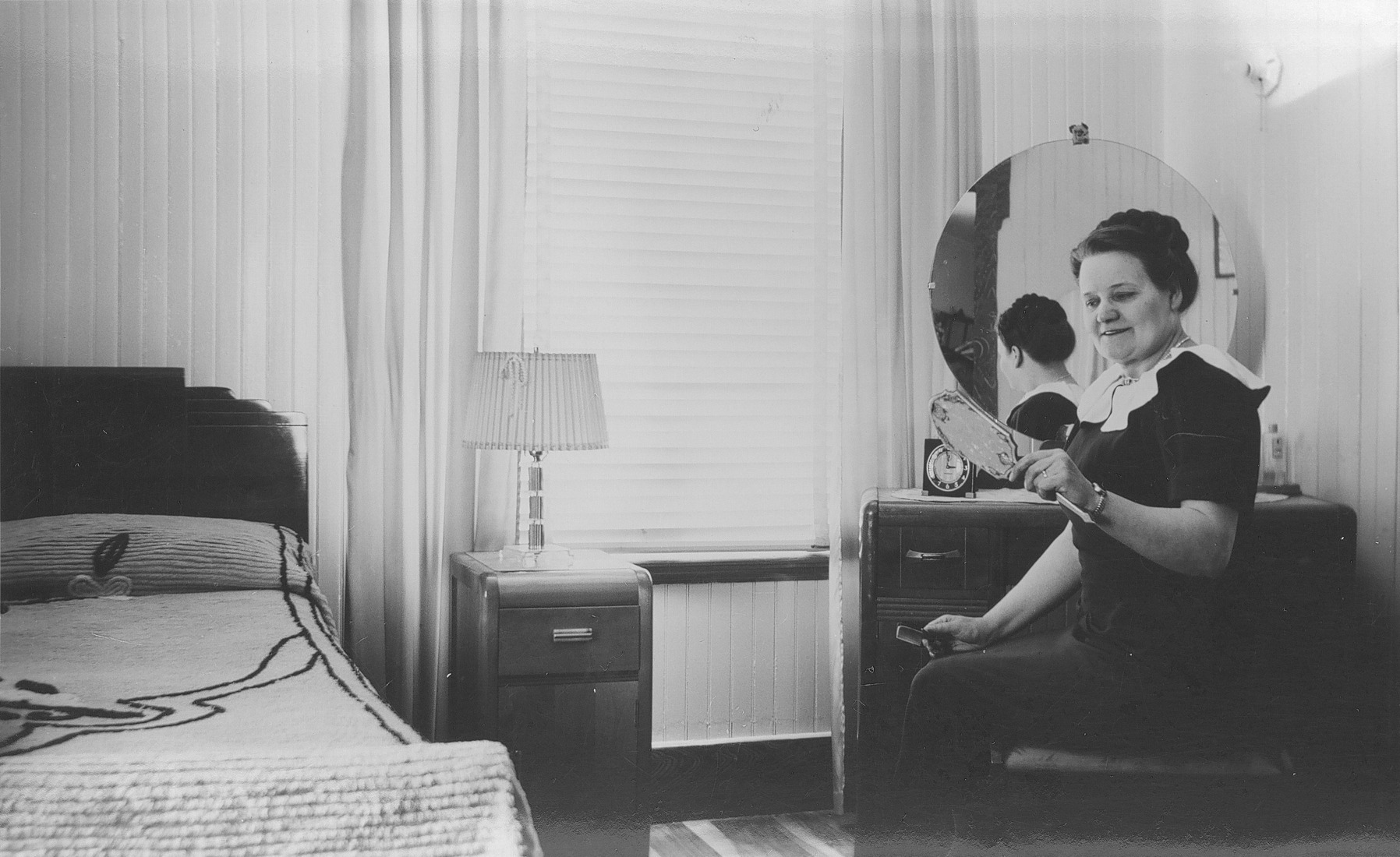

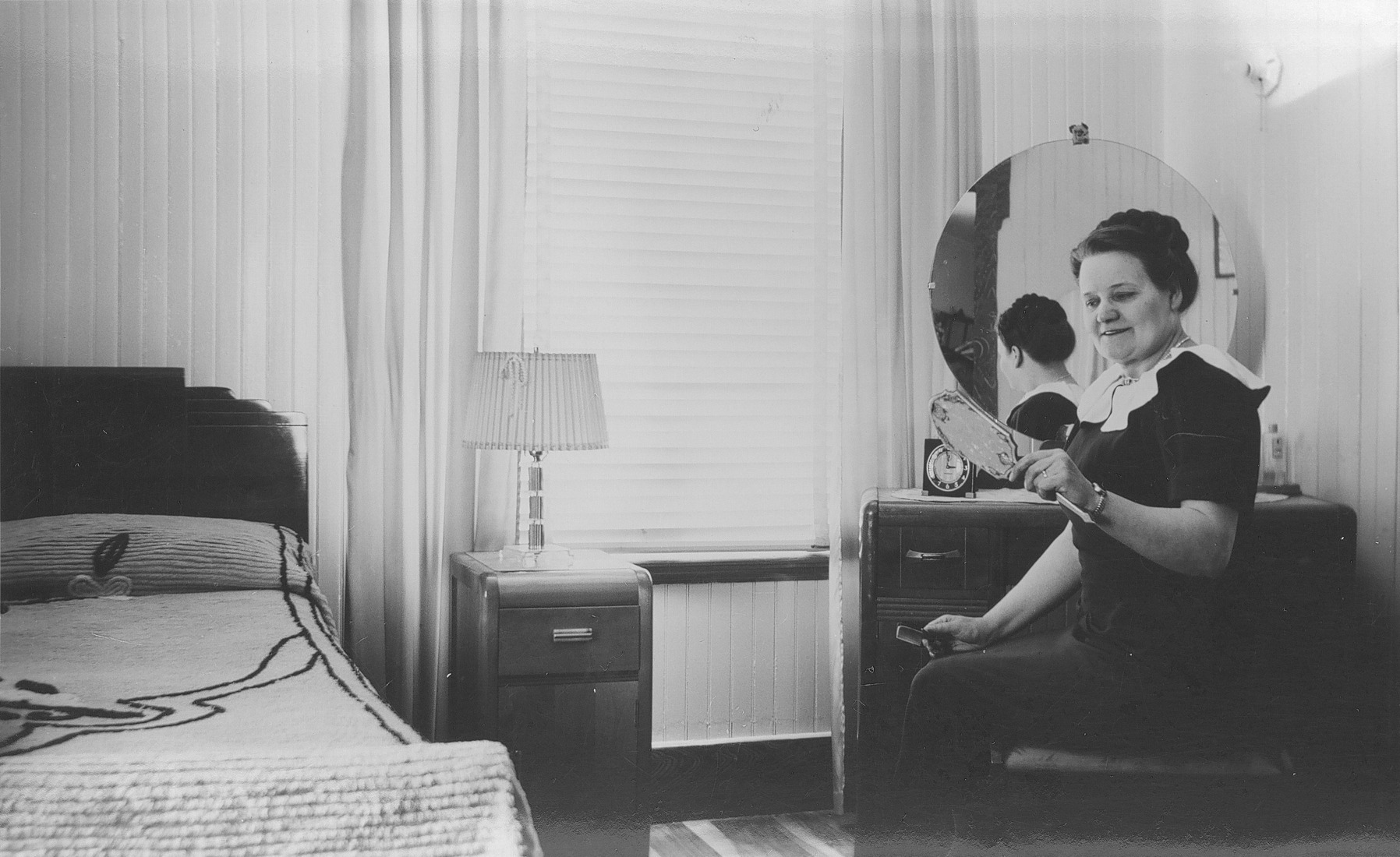

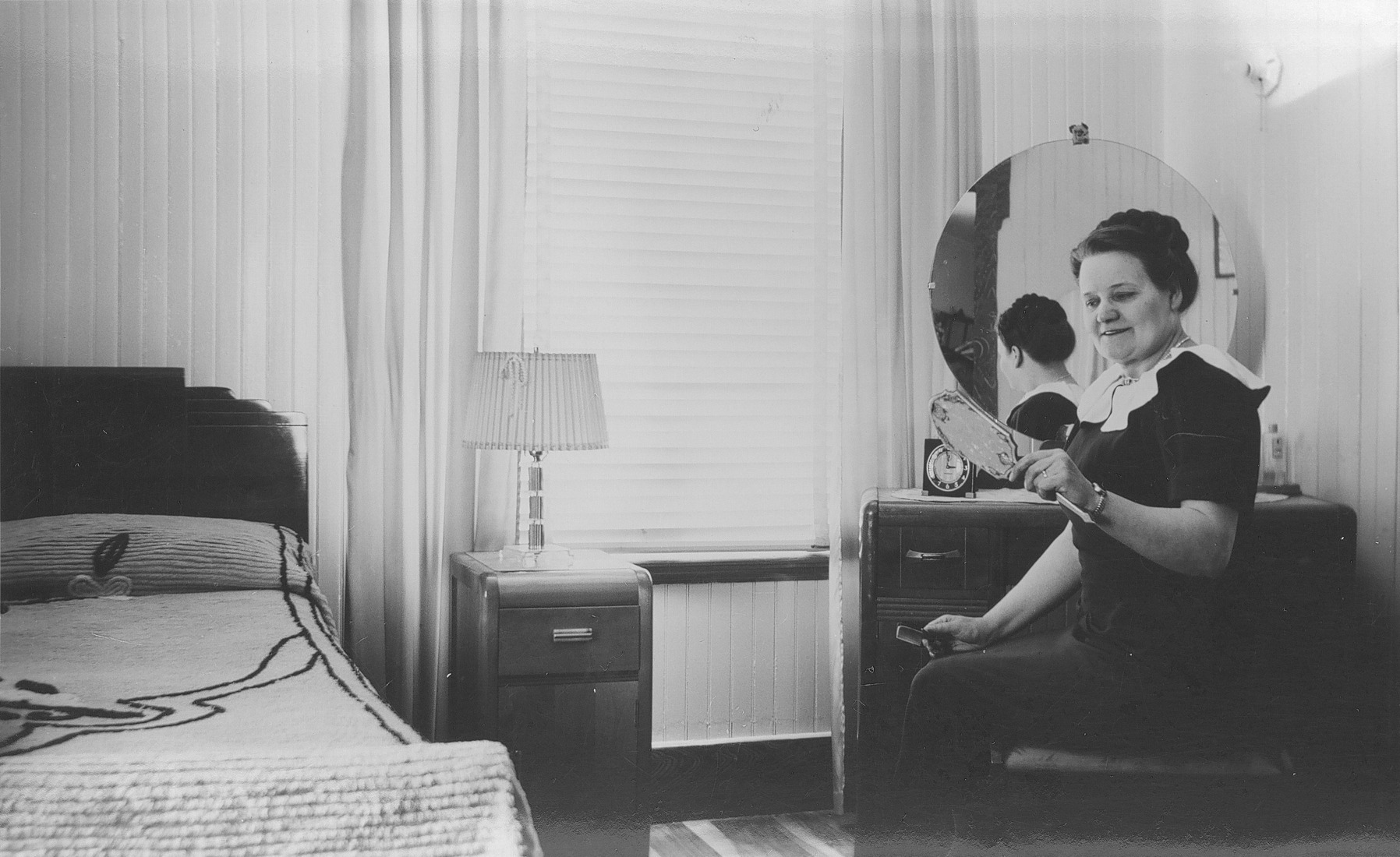

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

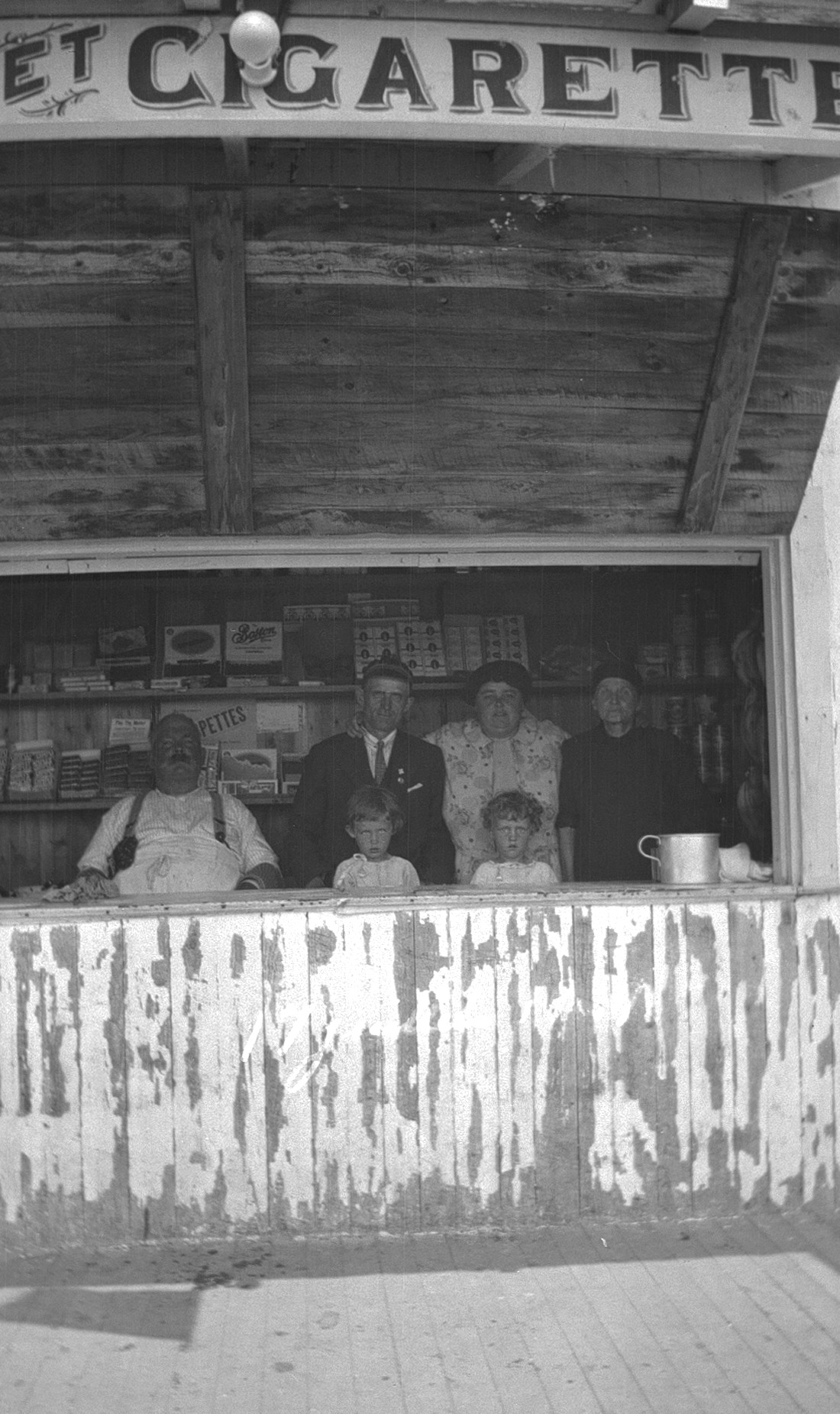

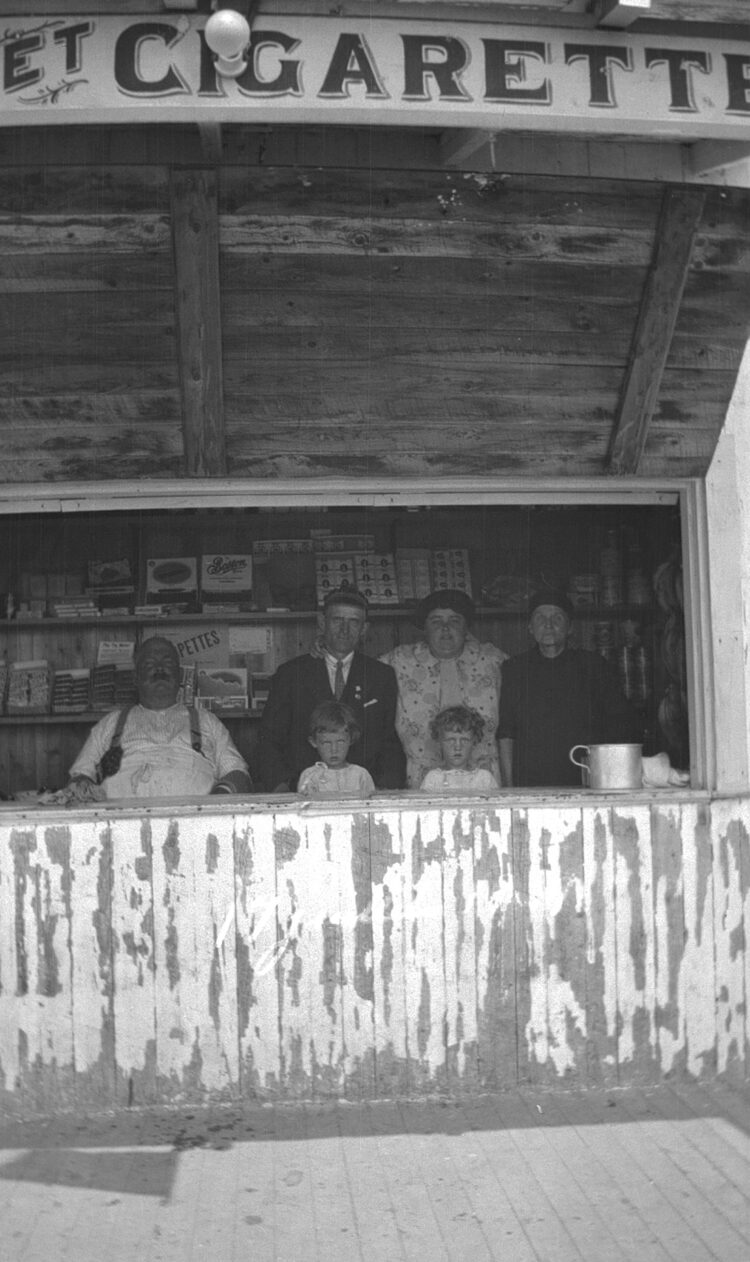

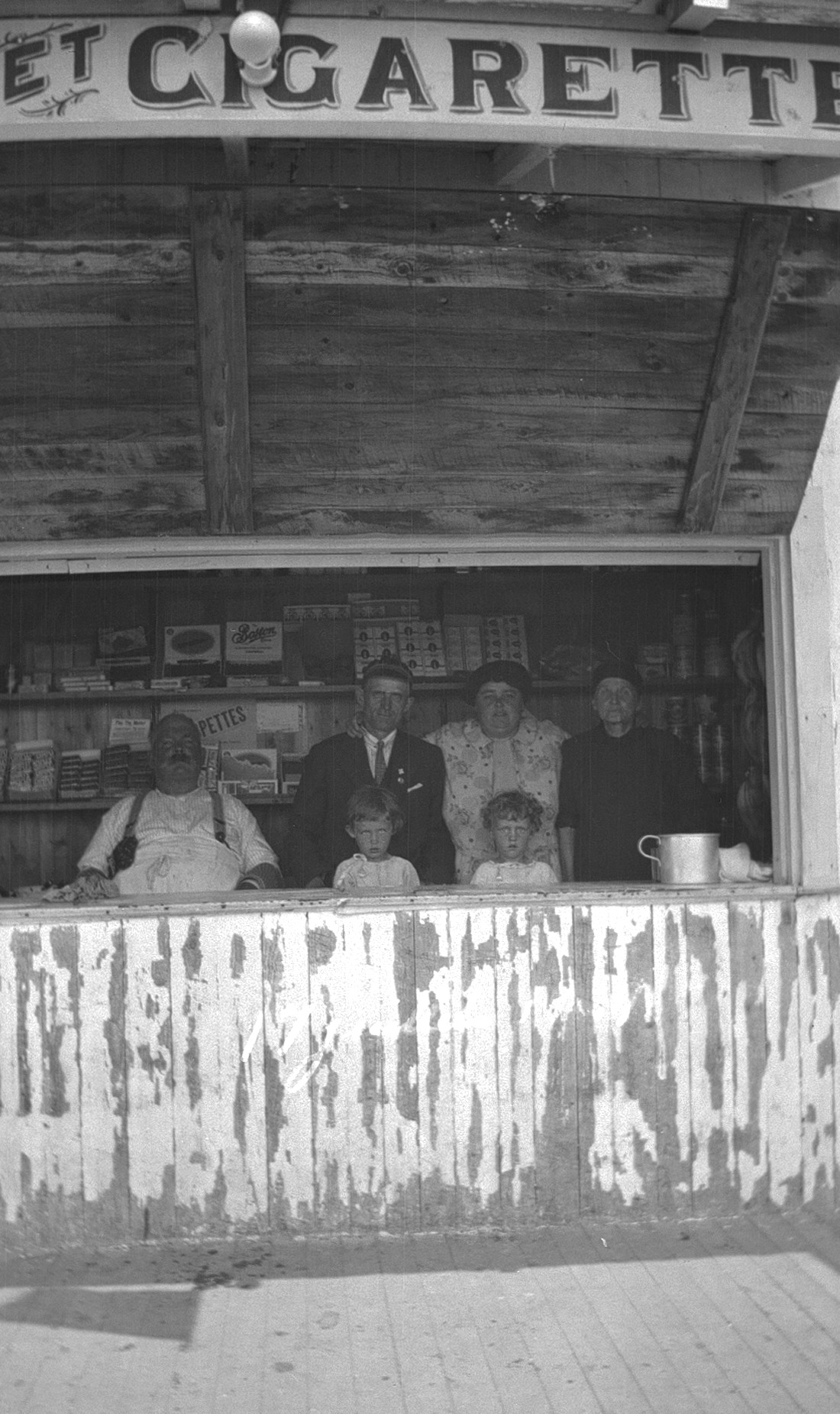

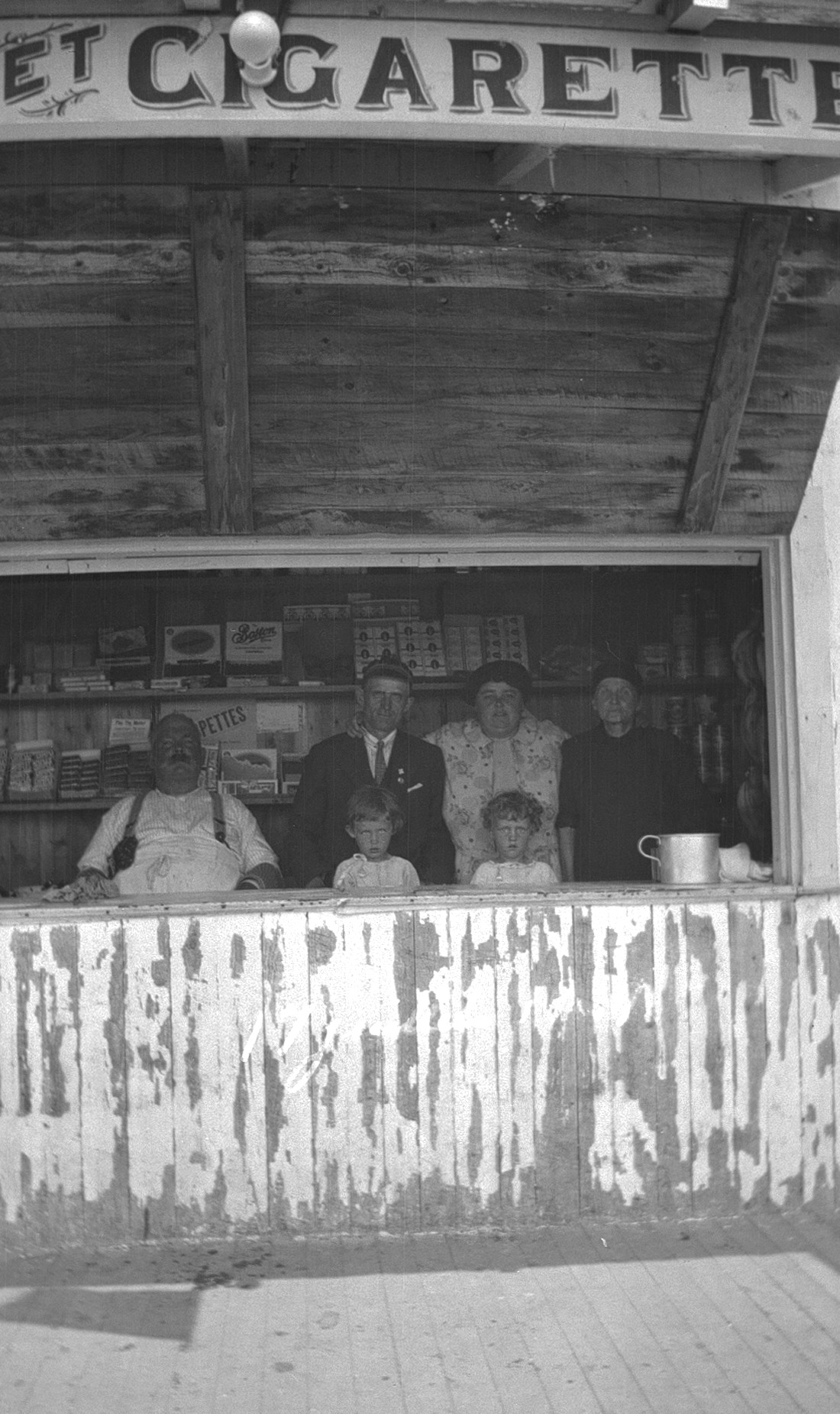

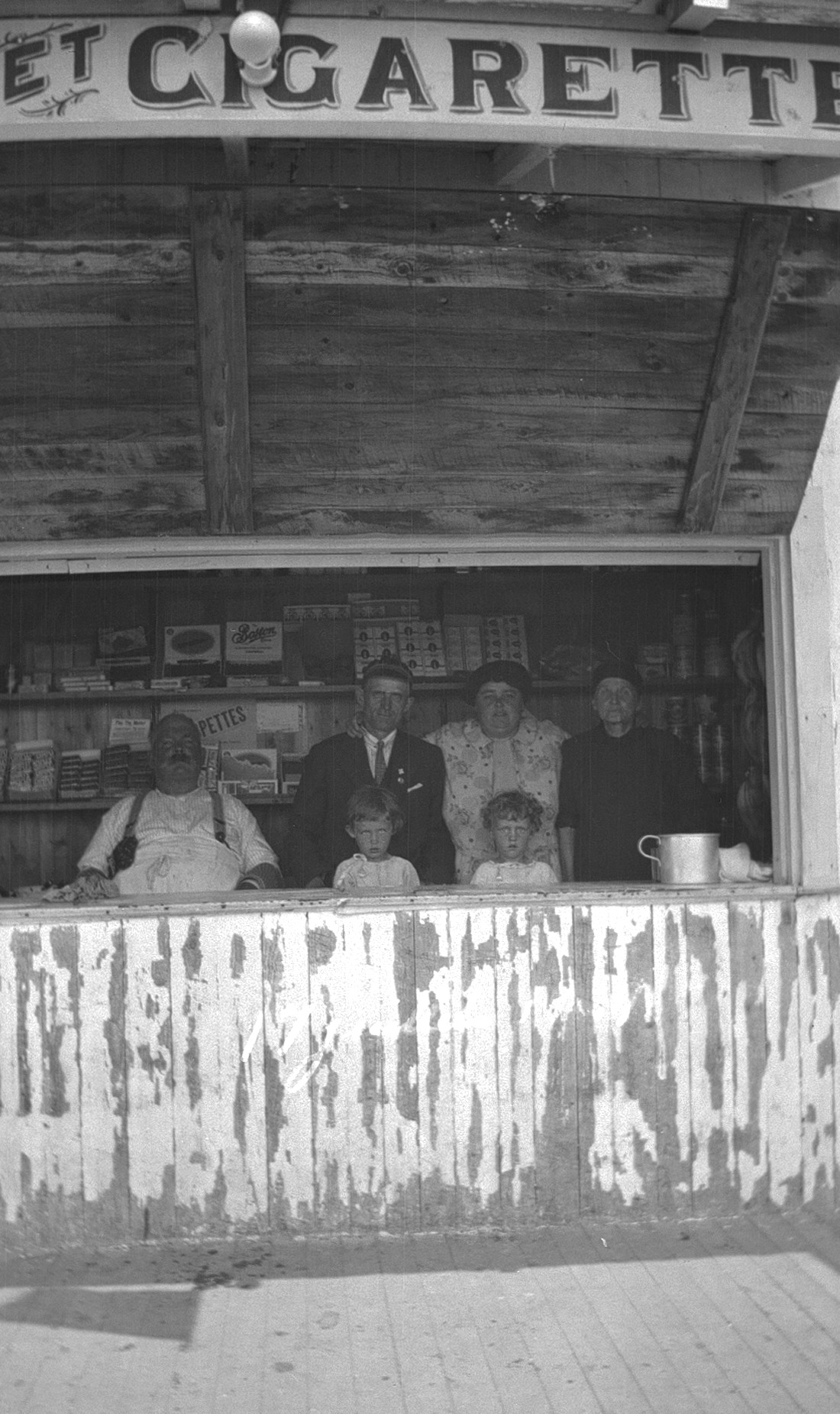

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

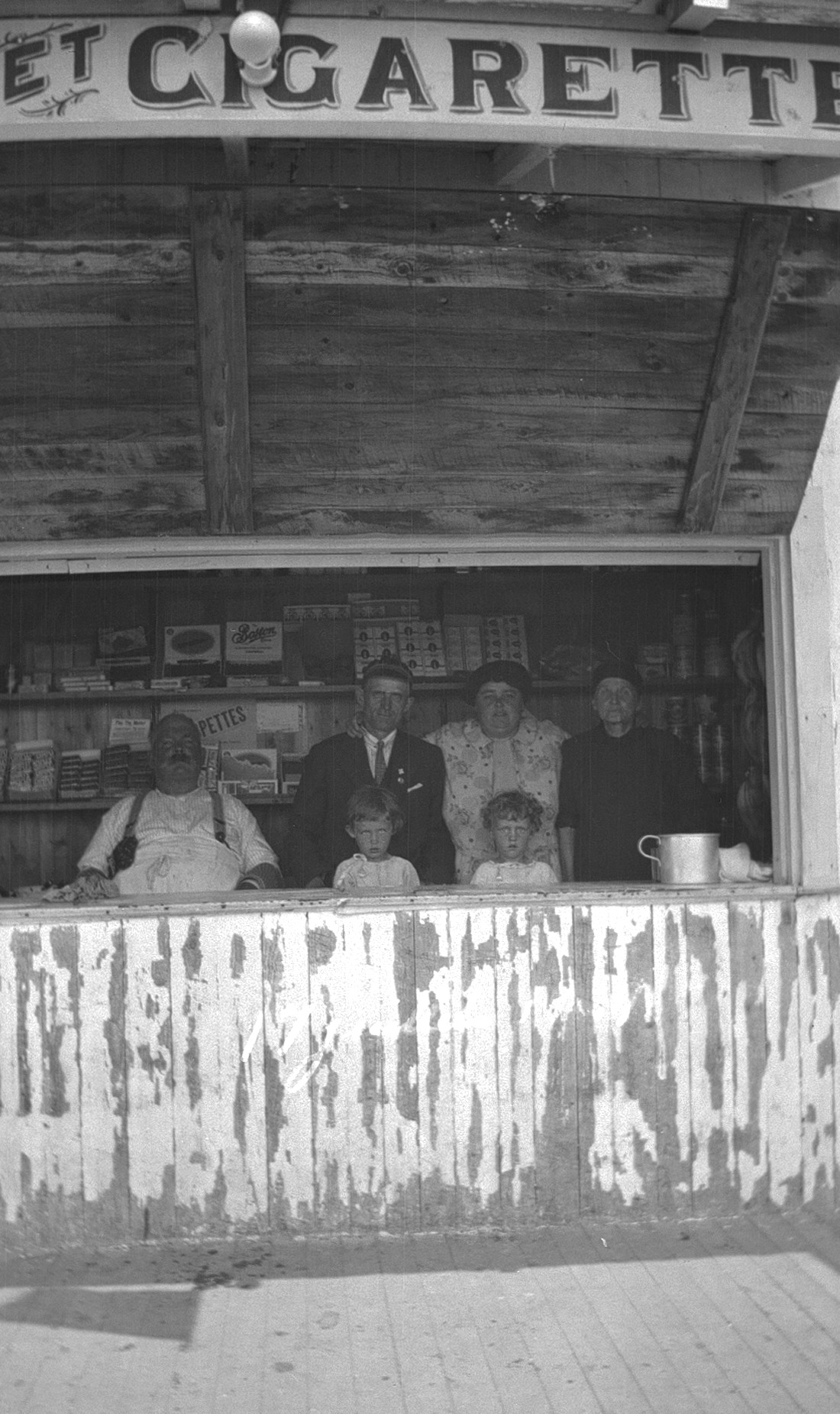

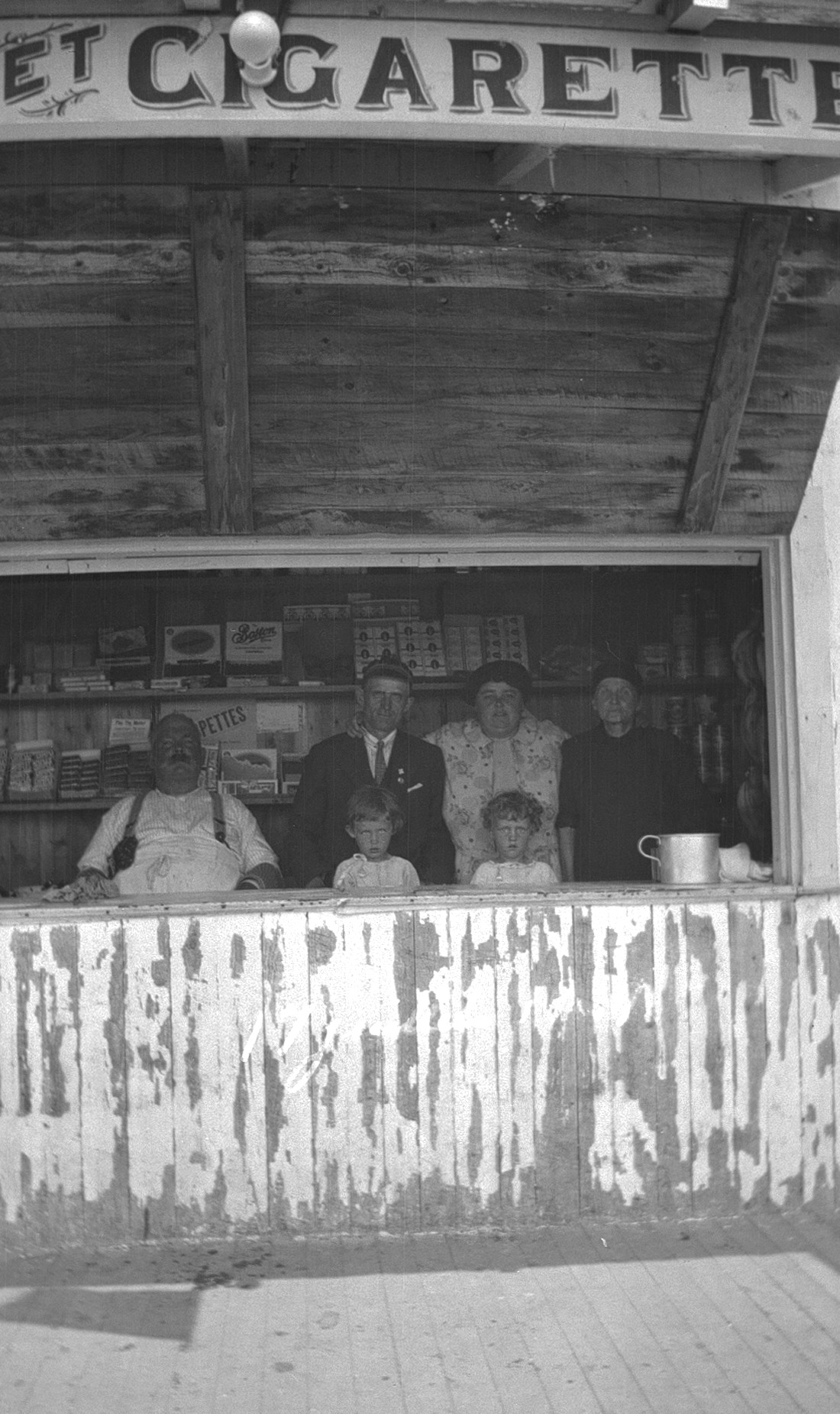

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

Marie-Anne St-Pierre, also a teacher, likely worked in one of the one-room schoolhouses of Saint-Alexandre. Her job was a challenging one: limited teaching materials, a poorly heated classroom, meagre pay, a large class, students of various grade levels, and an often solitary life. Such was the daily reality of rural schoolteachers.

When Marie-Alice Dumont was hospitalized in Rivière-du-Loup in 1936, she took the opportunity to document the daily life of the nursing staff. Beyond the medical care, there were also moments of amusement like this one, where three nurses are caught mid-performance: one at the piano, another on the violin and the third playing the flute.

The photographs Dumont took at the Rivière-du-Loup hospital in 1936 provide valuable insight into the work of healthcare staff in early 20th-century Quebec. This image is a beautiful example.

According to some historians, the bicycle, which gained popularity around the turn of the 20th century, offered women a temporary escape from the domestic sphere. In the 1930s and 1940s, cycling was the most accessible means of transportation for women in rural areas, since it was still only men who drove cars!

Sister Jeanne-de-la-Trinité, a Sister of Charity, smiles warmly at Dumont’s camera. She was part of the teaching staff at the convent in Saint-Alexandre.

In Quebec’s convents, girls were taught the basics of the “domestic arts” until the 1960s. This curriculum later evolved into home economics, which was offered to both boys and girls in secondary schools until 2006.

The women of the Dumont family took part in farm work. In this photo, Marie Pelletier (second from the left) stands among the men, sorting potatoes.

As this multigenerational portrait shows, many of Dumont’s clients could proudly say they had known their great-grandmother, or even their great-great-grandmother.

Dumont worked in a profession that was quite unusual for a woman of her time. The same could be said of her three assistants, including Lucille Bérubé, shown here standing in front of Dumont’s studio.

Here is a striking portrait of Pierrette Lavoie in her flight attendant uniform. Up until at least the 1960s, the hiring criteria for stewardesses were extremely strict. At Trans-Canada Air Lines, for instance, candidates had to be young, attractive, single, bilingual, slender, healthy and neither too tall nor too short.

Marie-Alice Dumont photographed many of the local shopkeepers in her village. Here, Camille Pelletier and his wife pose in front of their store, the oldest shop in Saint-Alexandre parish.

On a sunny afternoon in 1950, Marie-Alice Dumont visited the Pelletier store for a photo session with the women of the household. Mrs. Camille Pelletier and her daughters posed alone or together, in various settings that reflected their daily lives. In this scene, Mrs. Pelletier sits at her vanity in the modern comfort of her bedroom.

The people who posed for Dumont’s camera often wore their finest clothes. Here, Marie-Claire Landry is dressed in a fox fur stole, a fashion staple of the time. In fact, during the 1930s, fox farming contributed to the local economy in Kamouraska.

From the very beginning of her photography career, Marie-Alice Dumont documented the life of her community with a particular focus on local trades and traditions, as if she were paying tribute to them. Many of these images, like this one, are marked by their simplicity and authenticity.

The men in Marie-Alice Dumont’s photographs were often her family, neighbours or close friends. Her portraits reflect her connection to her subjects and her community. Beyond the studio, her camera, guided by her curiosity, captured everything: road workers, the local doctor caring for patients, and her father, Uldéric, tackling day-to-day chores. In the studio, she photographed fathers, friends, sons, suitors and workers.

Many men in Dumont’s era were skilled tradesmen who played vital roles in their community. In 1952, during the creation of Saint-Alexandre’s centennial souvenir album, the family of Ludger Chouinard used this photograph to pay tribute to the local shoemakers, their “homage to cobblers.”

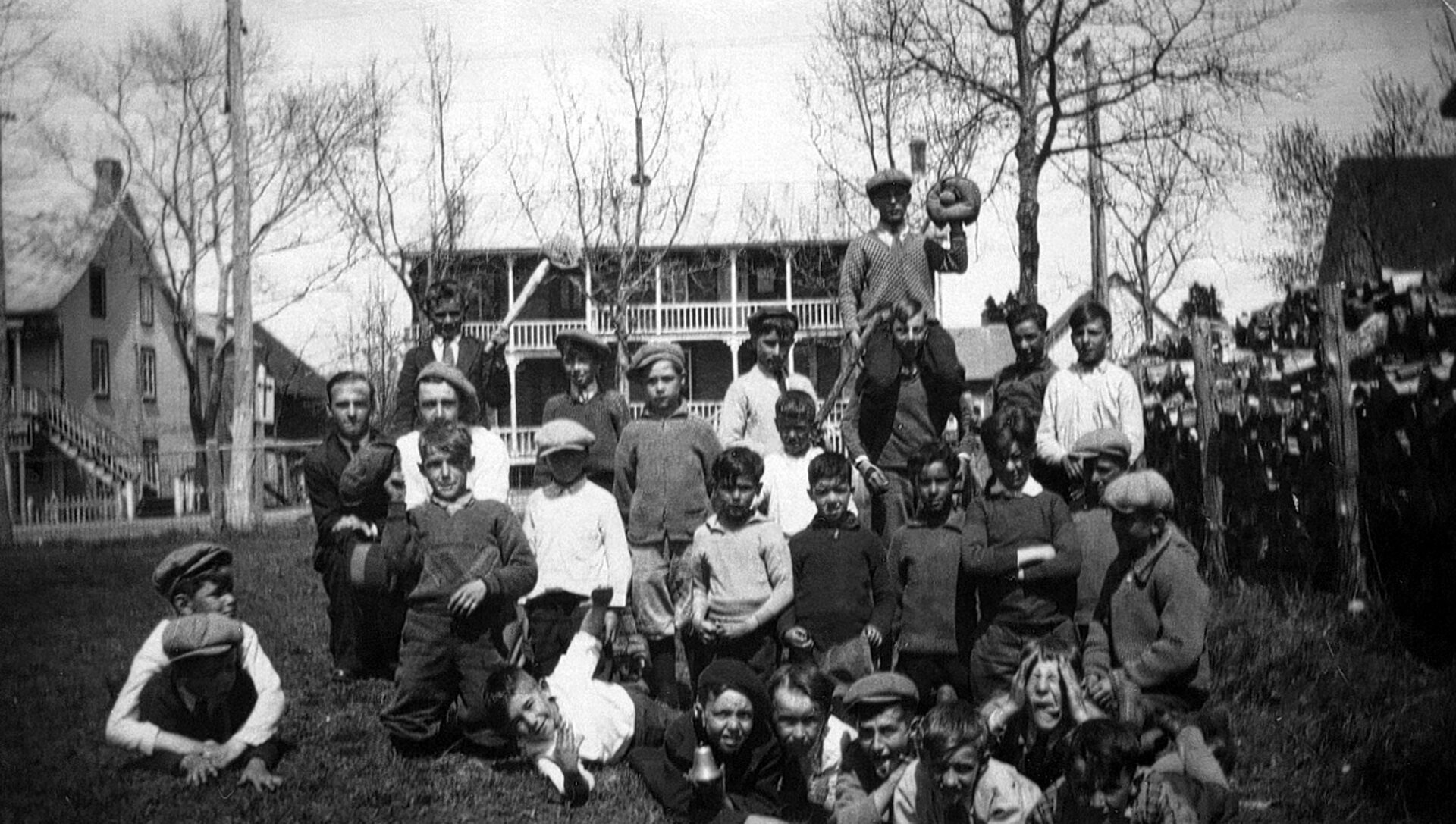

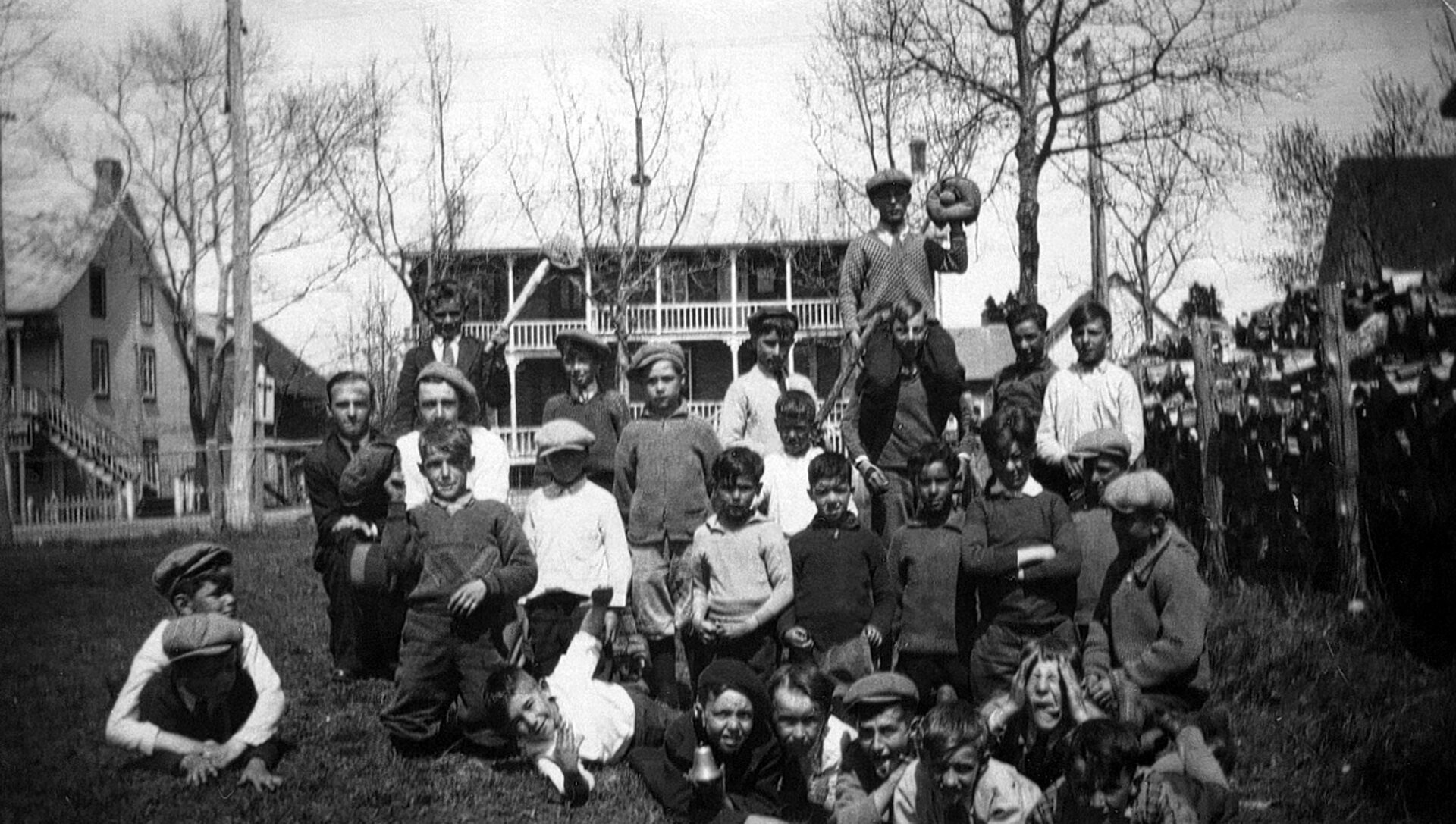

Armed with pickaxes and shovels, the men and boys of the village built and maintained essential public infrastructure, including sewers and aqueducts. This is how towns and villages across Quebec began to modernize in the early 20th century.

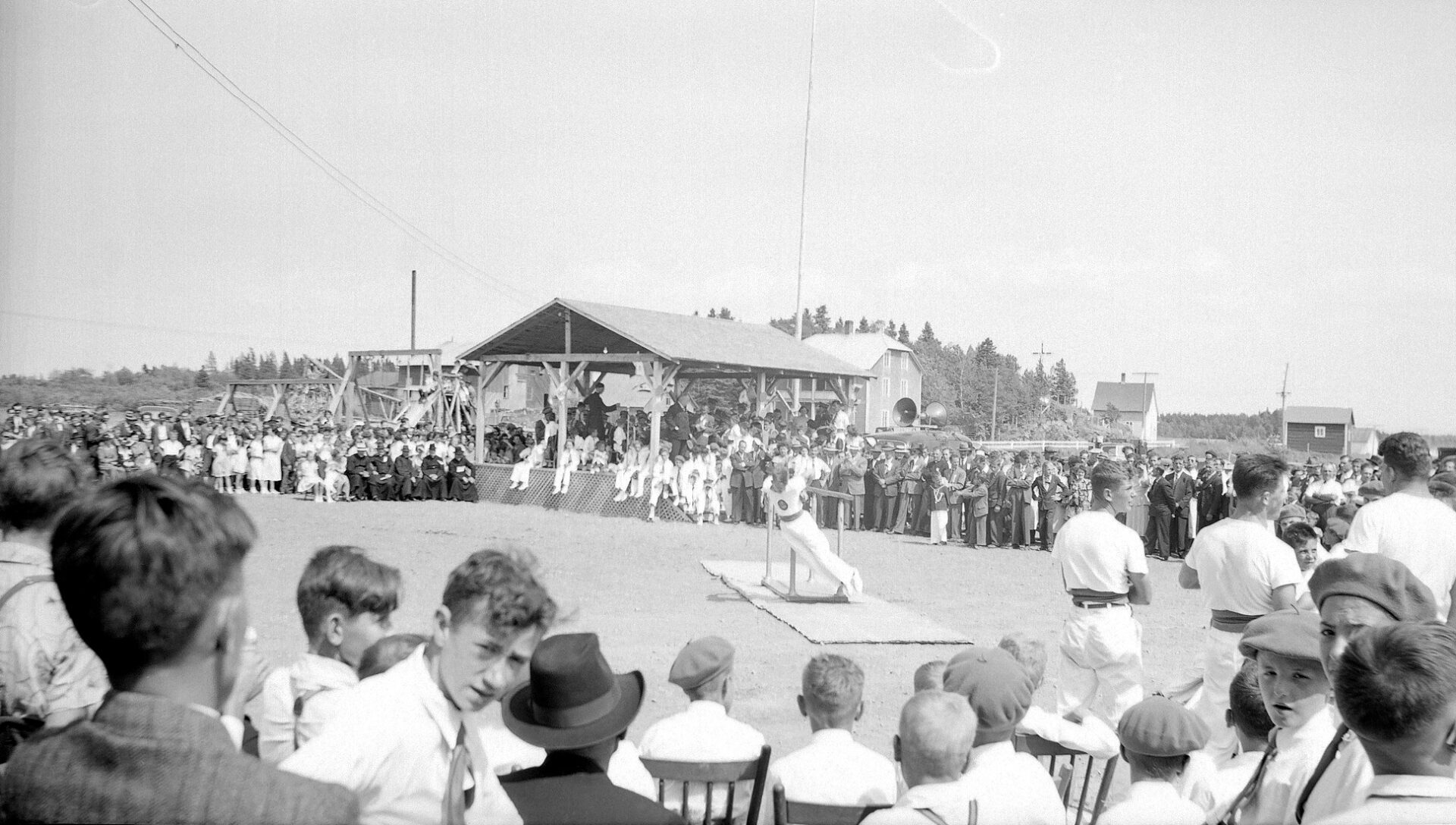

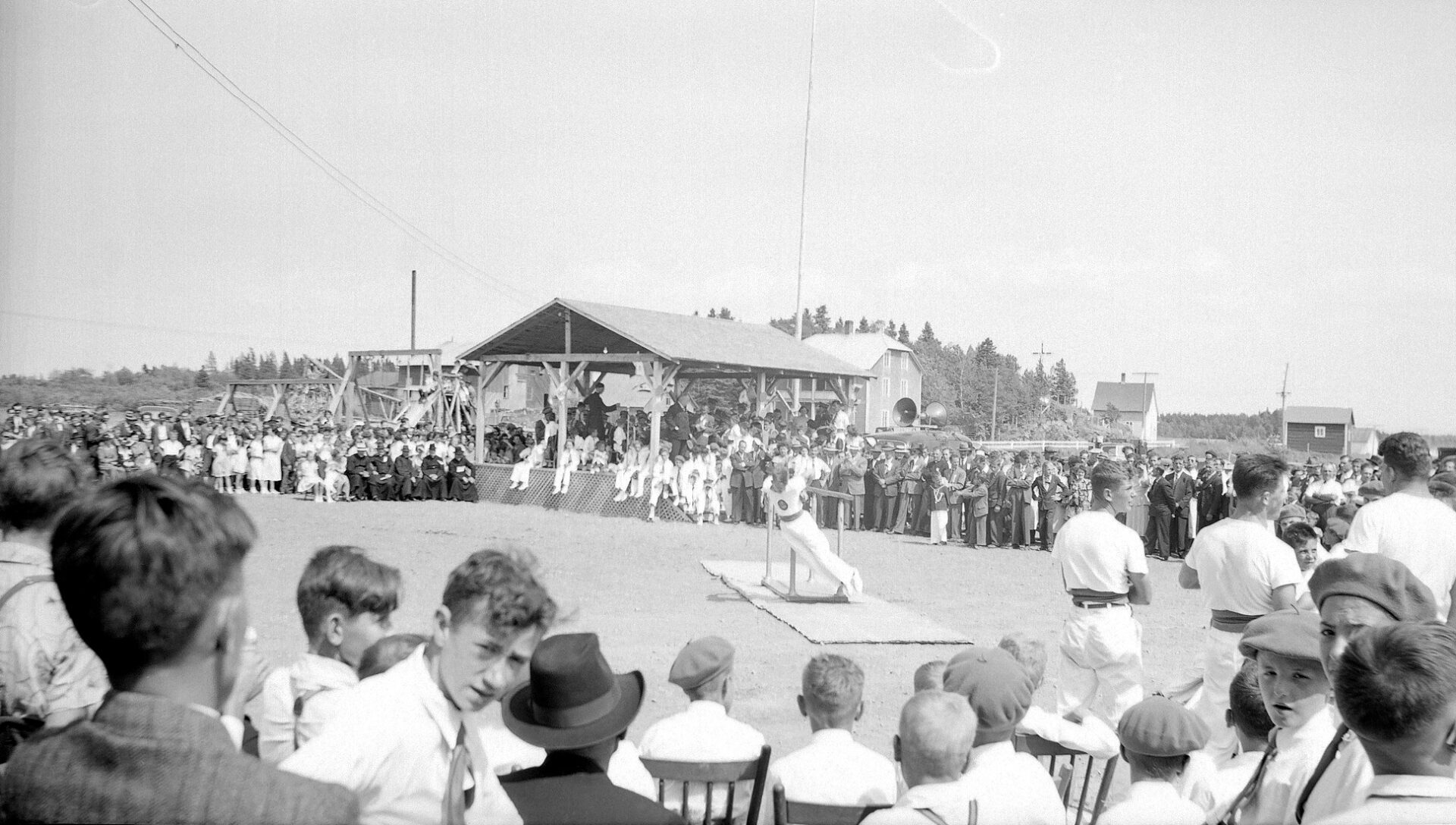

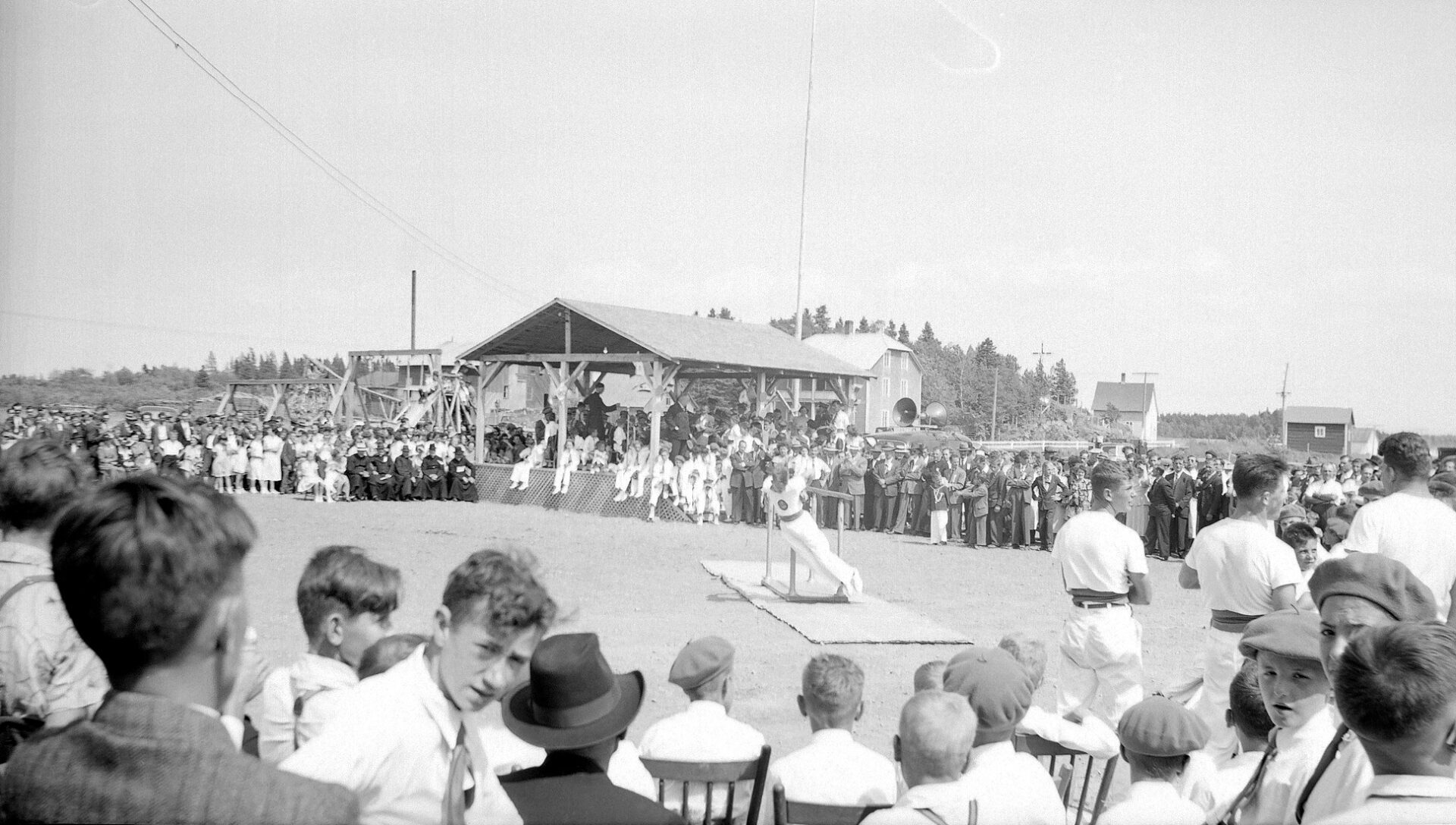

The entire village took part in the Saint-Alexandre centennial celebrations. The man behind the wheel of this tractor was no doubt proud to play a part in the event and to have loaned his machine for the parade of decorated floats.

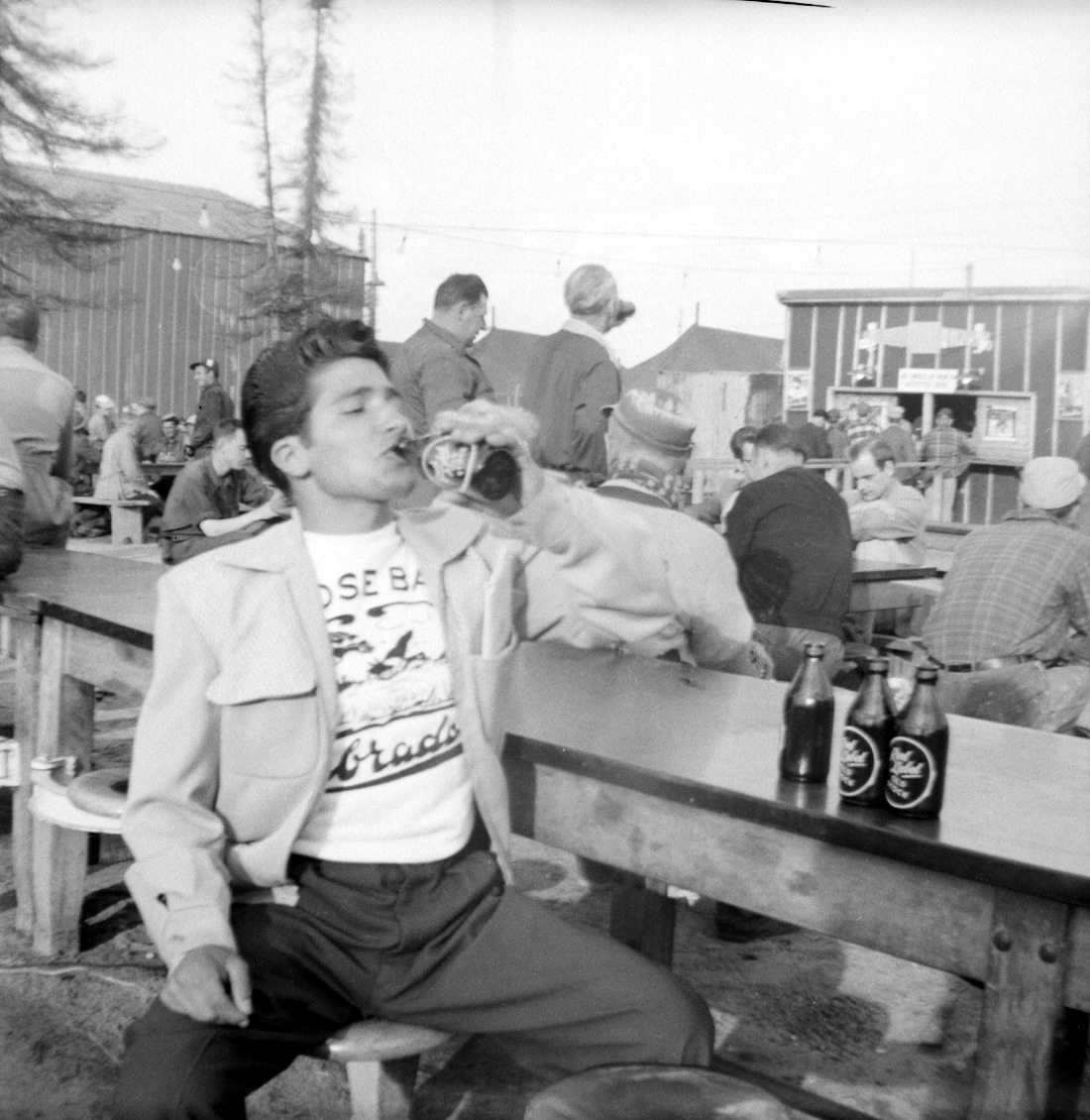

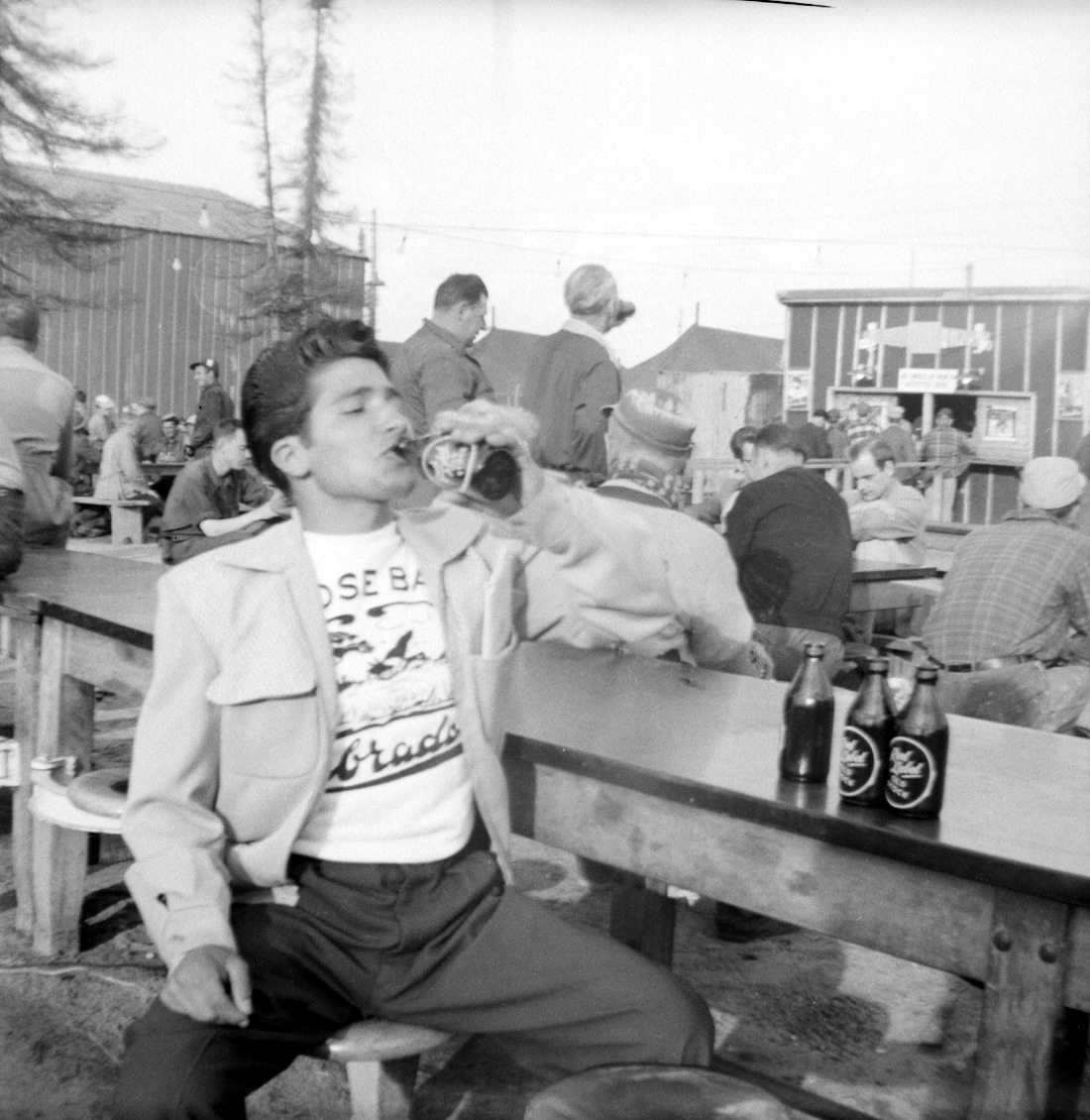

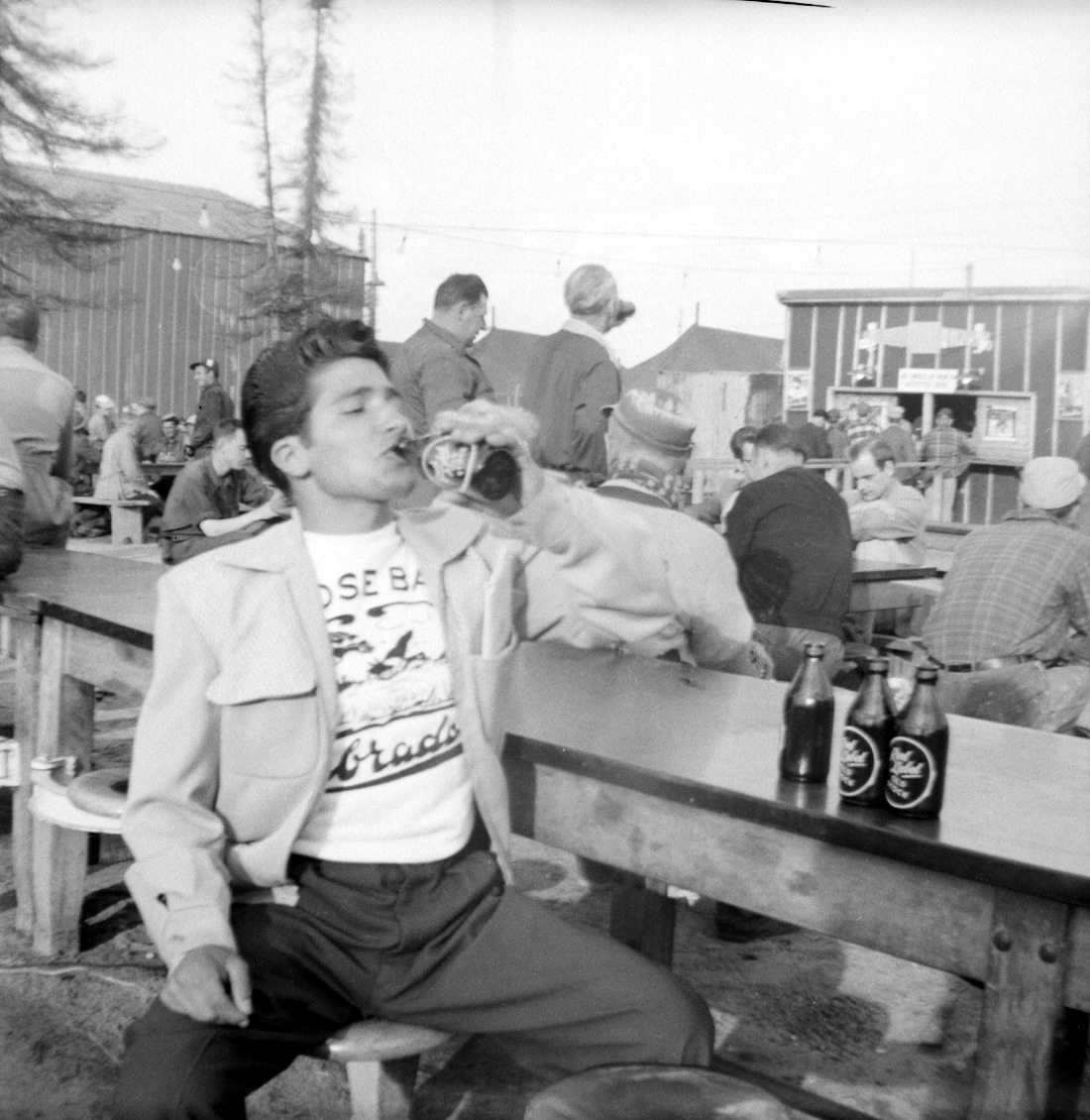

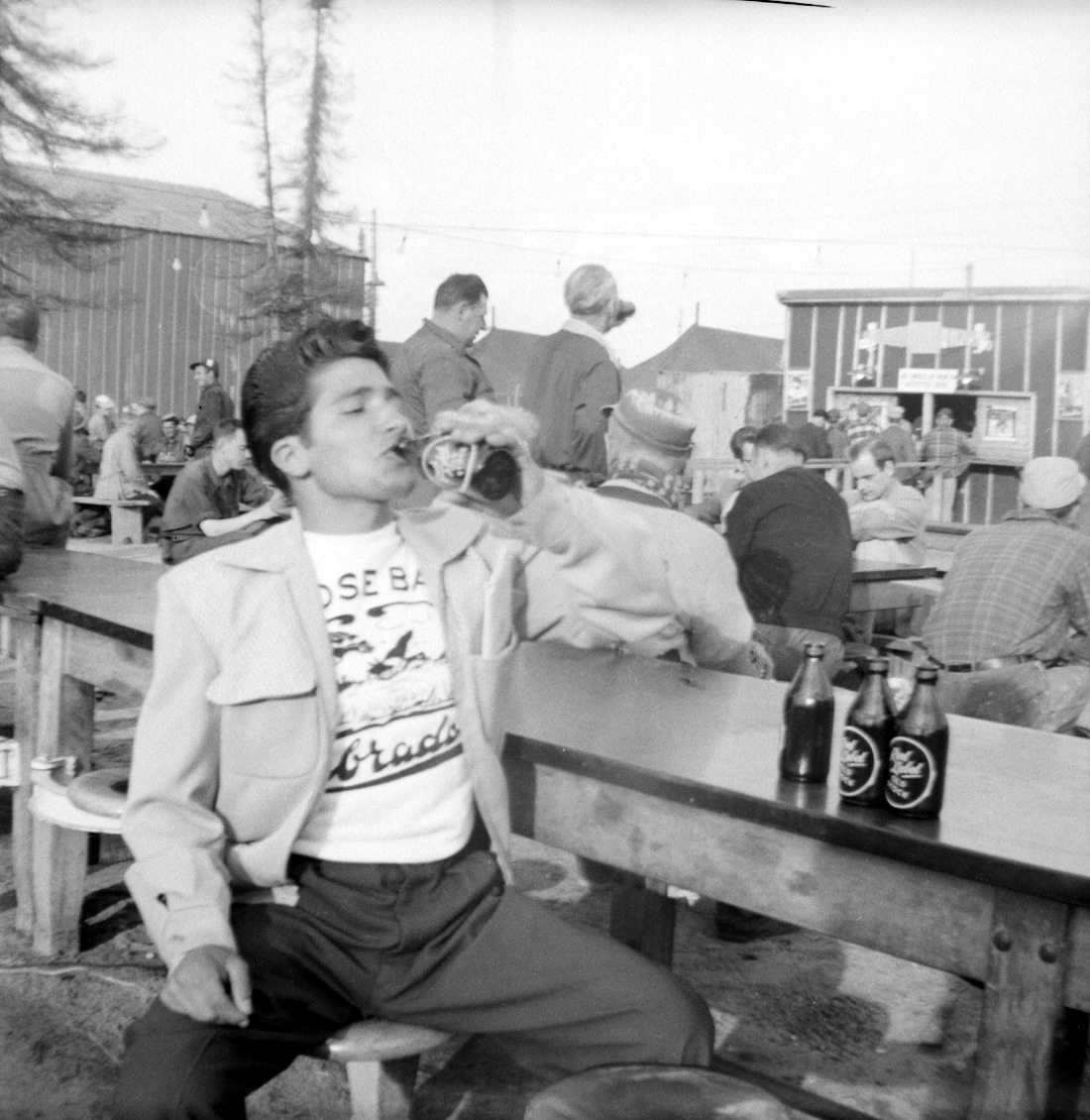

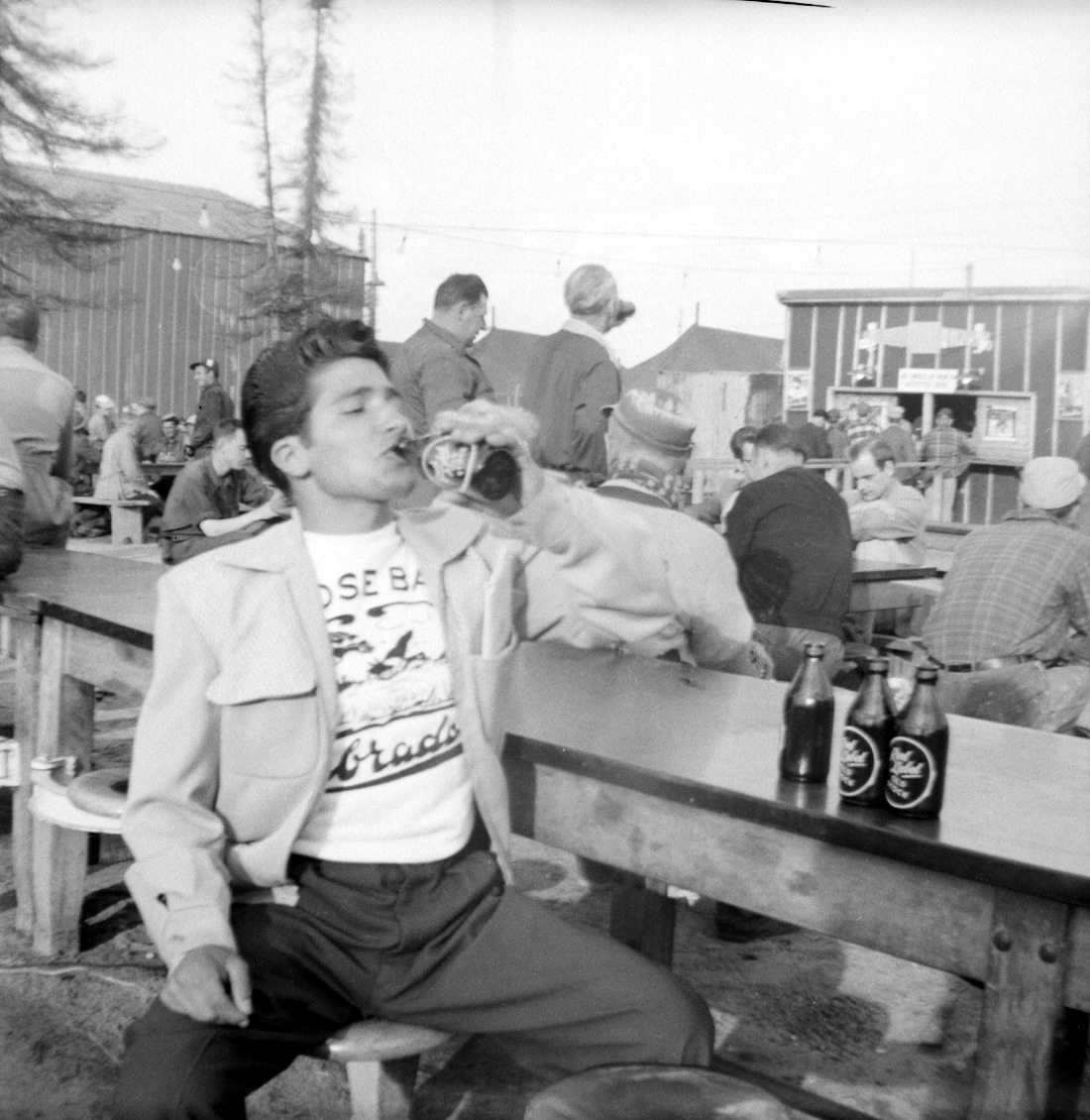

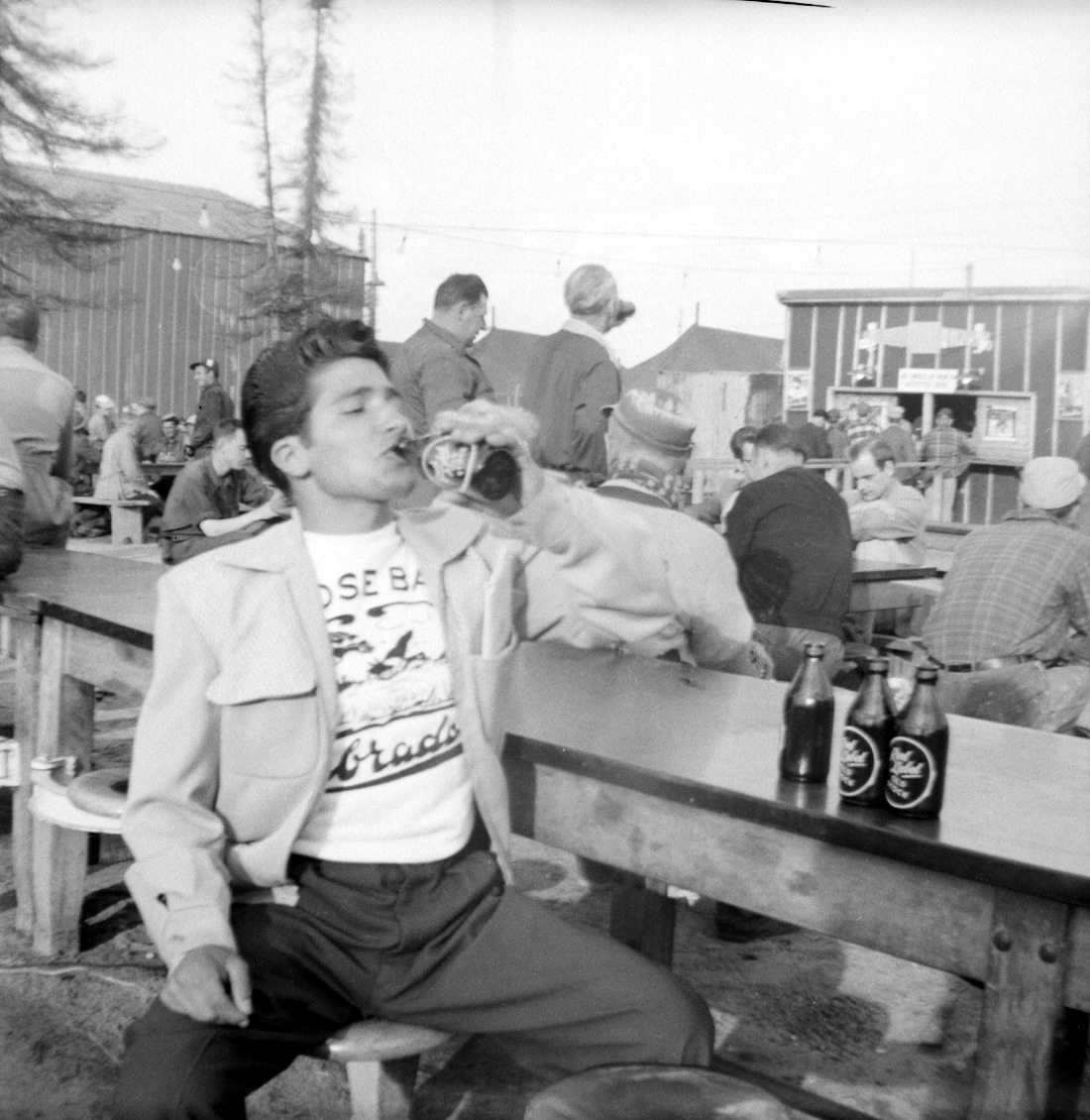

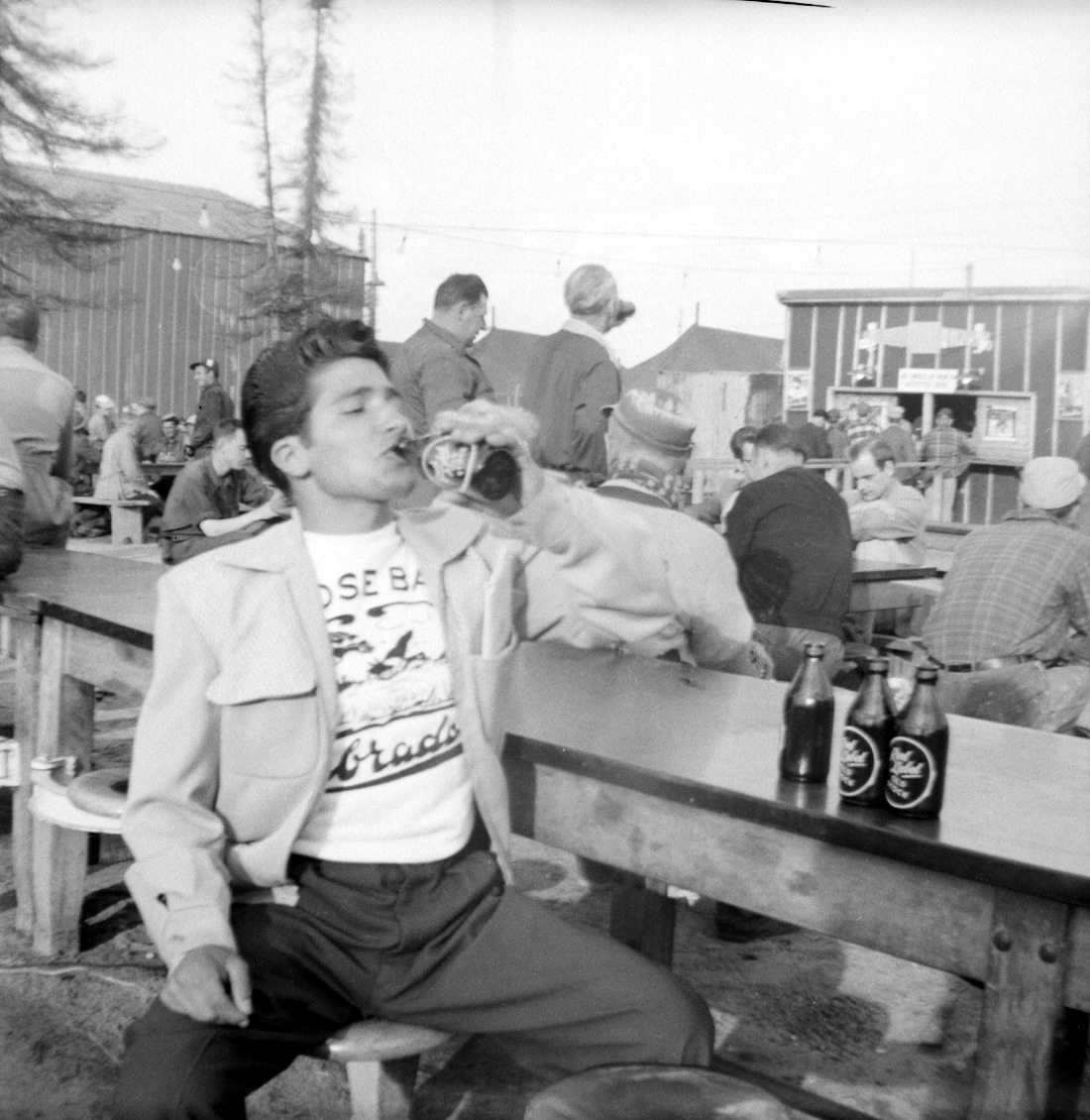

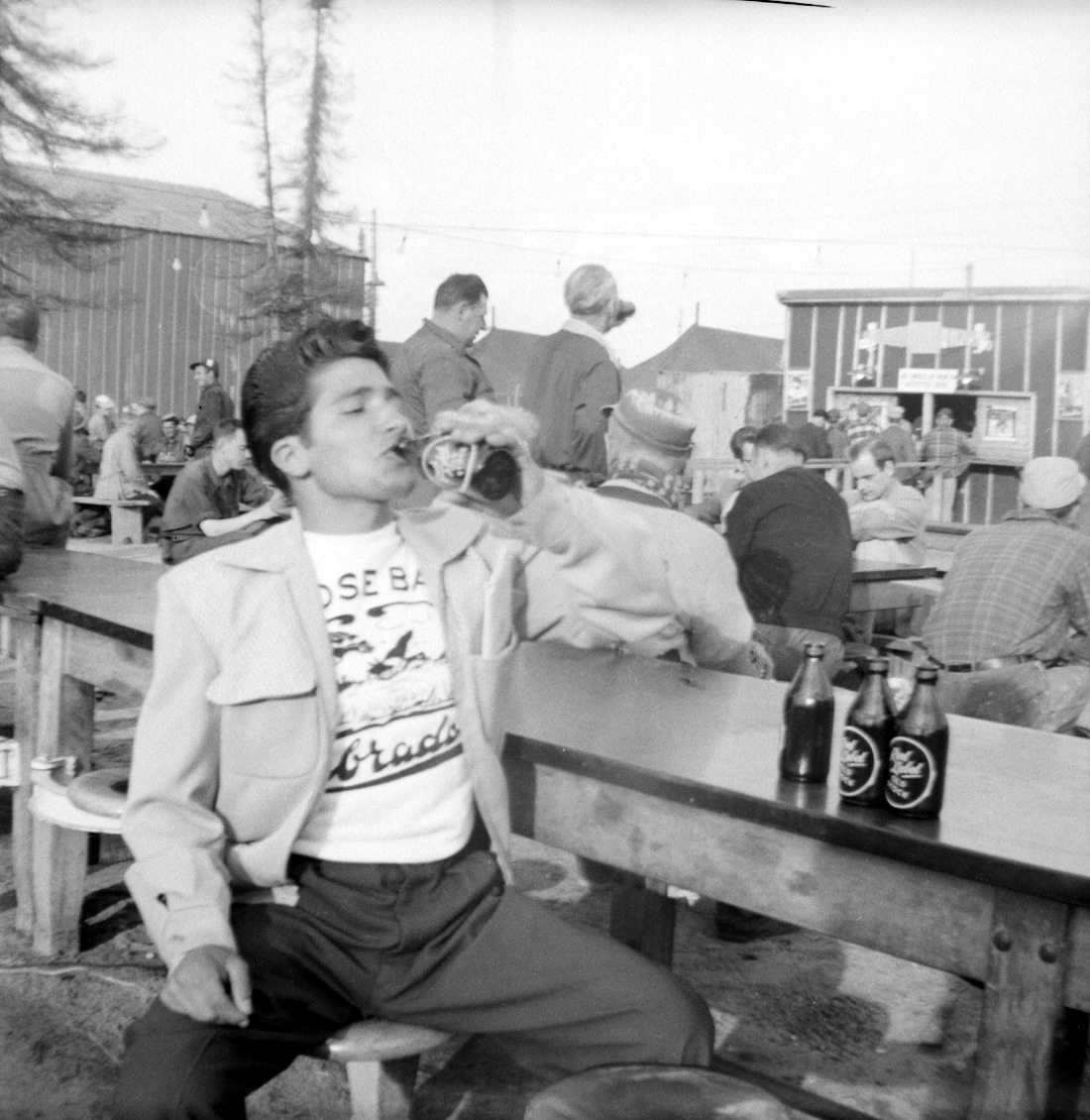

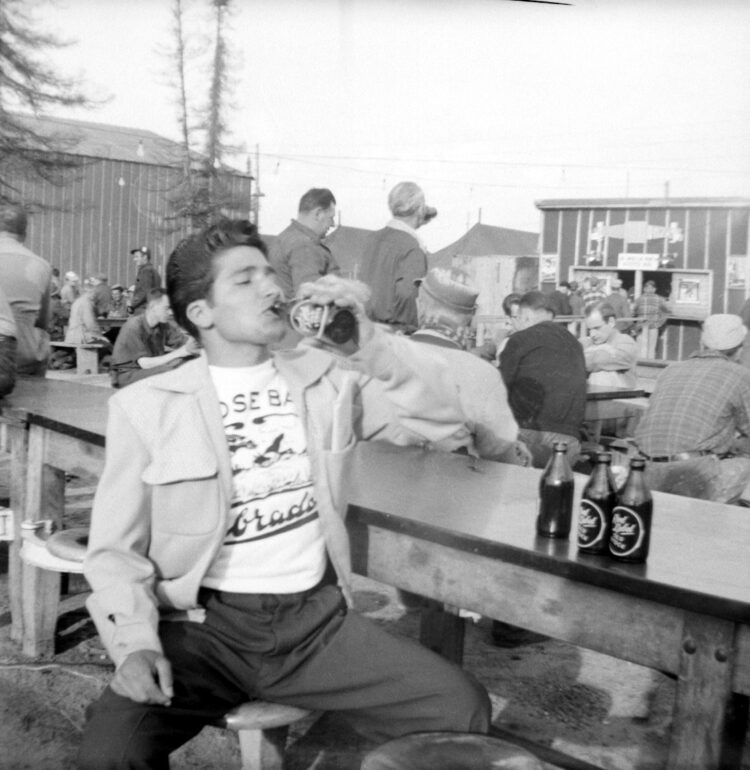

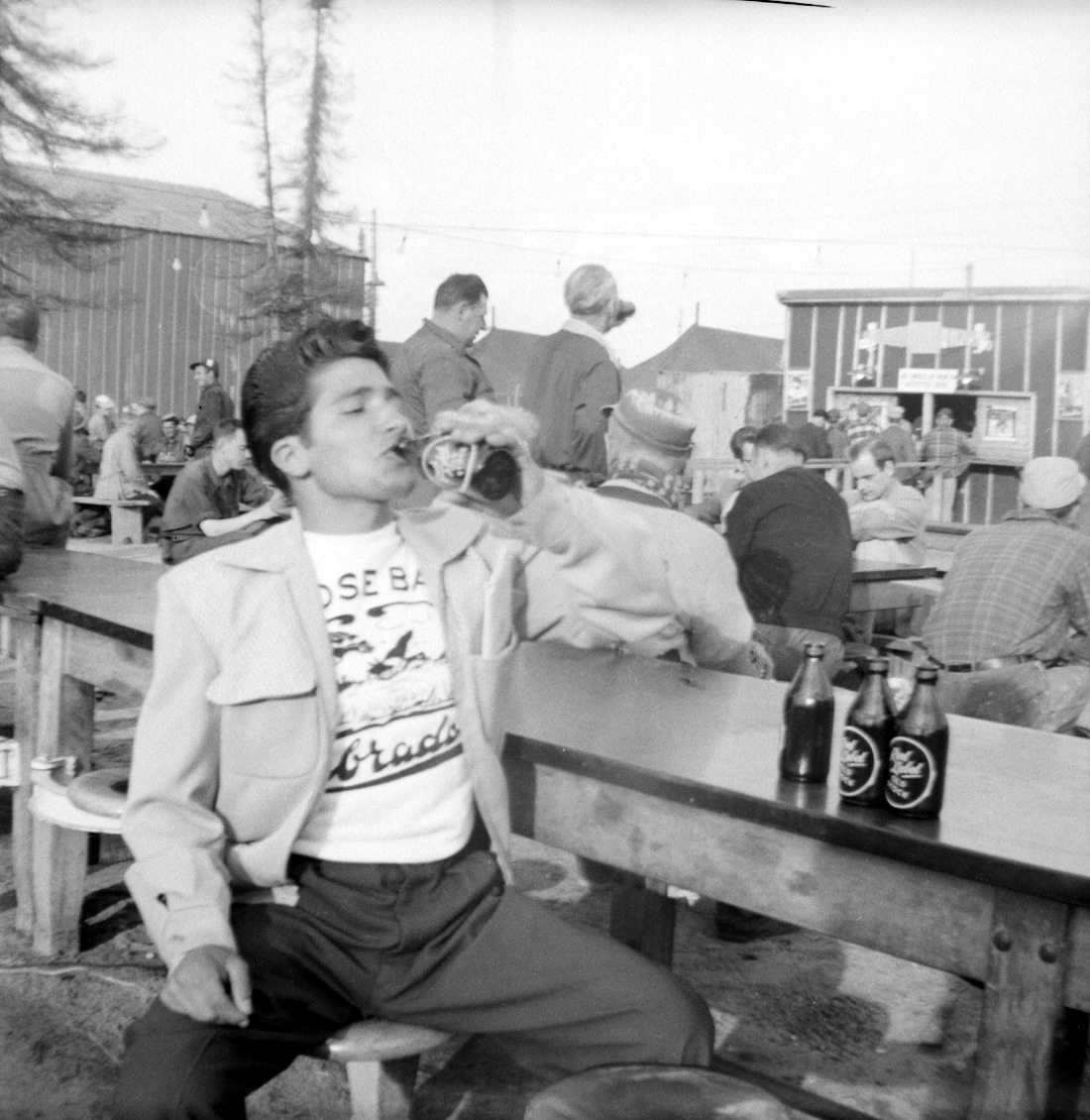

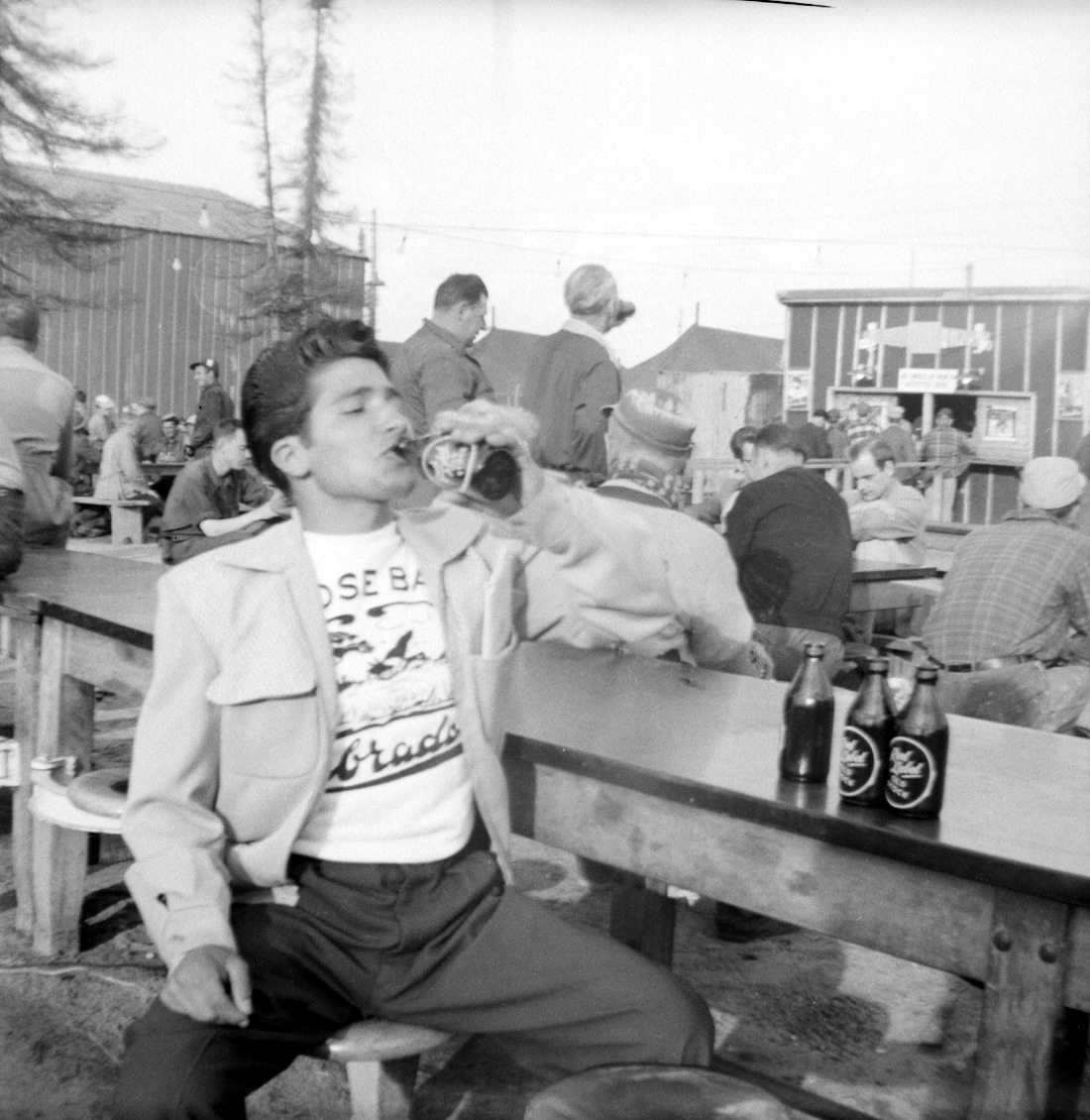

Several negatives preserved by Dumont appear to have been taken by amateur photographers who brought them in for development. In this image, a young man is pictured drinking a Red Label beer. It is part of a series of candid shots taken by two friends at a male-only worksite. It would have been surprising to see Dumont herself in such a setting like, for instance, an all-male dormitory!

In Dumont’s time, it was mostly men, like this physician, who held professional occupations: lawyers, accountants, engineers, doctors and notaries. In 1971, 35 years after this photo was taken, women still account for only 11% of those professions. But that number rose dramatically in the decades that followed, reaching 51% by 2006.

Uldéric Dumont had always taken care of his family’s firewood needs by harvesting this precious resource from his own land. Cutting firewood by hand saw was an enormous task.

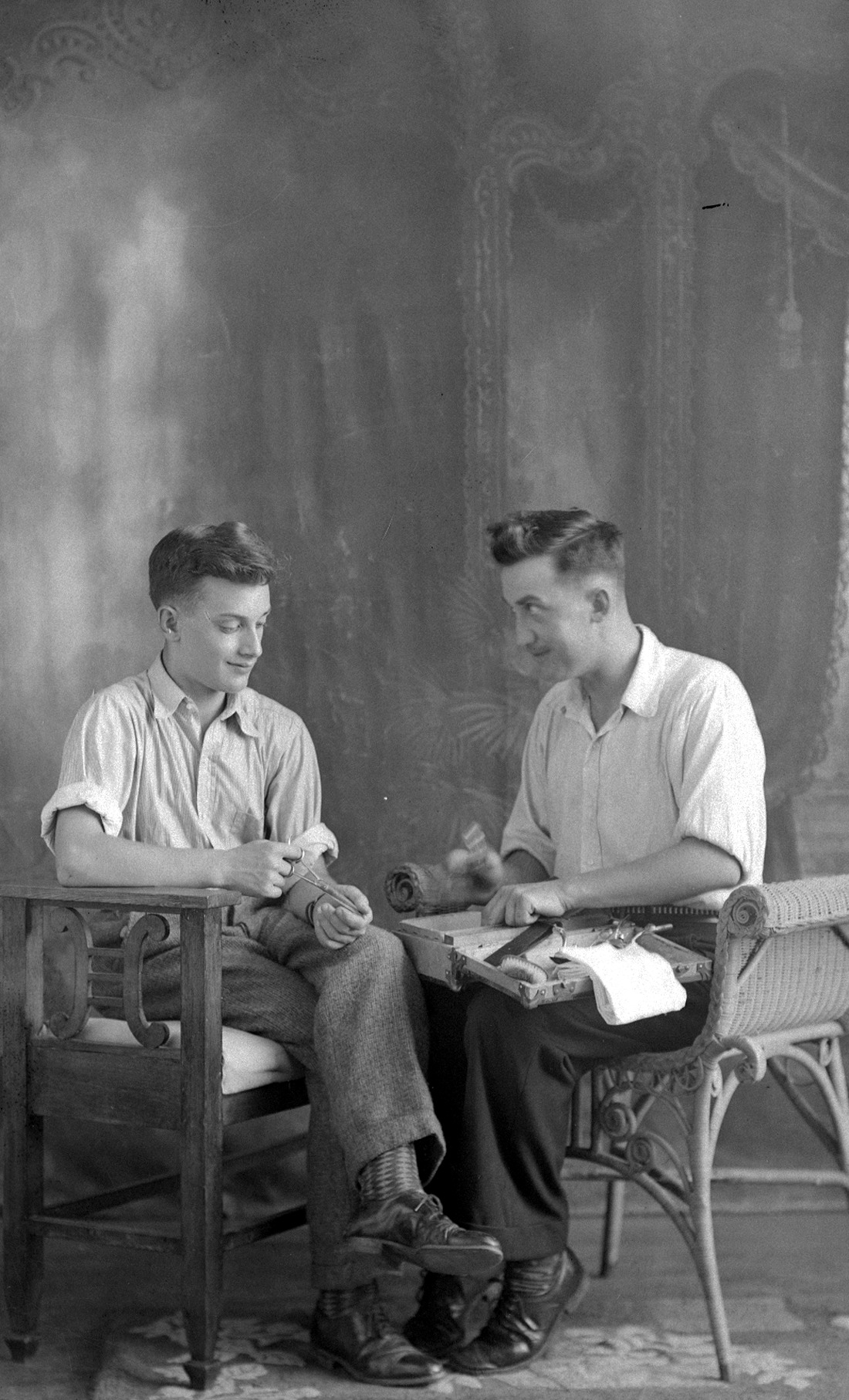

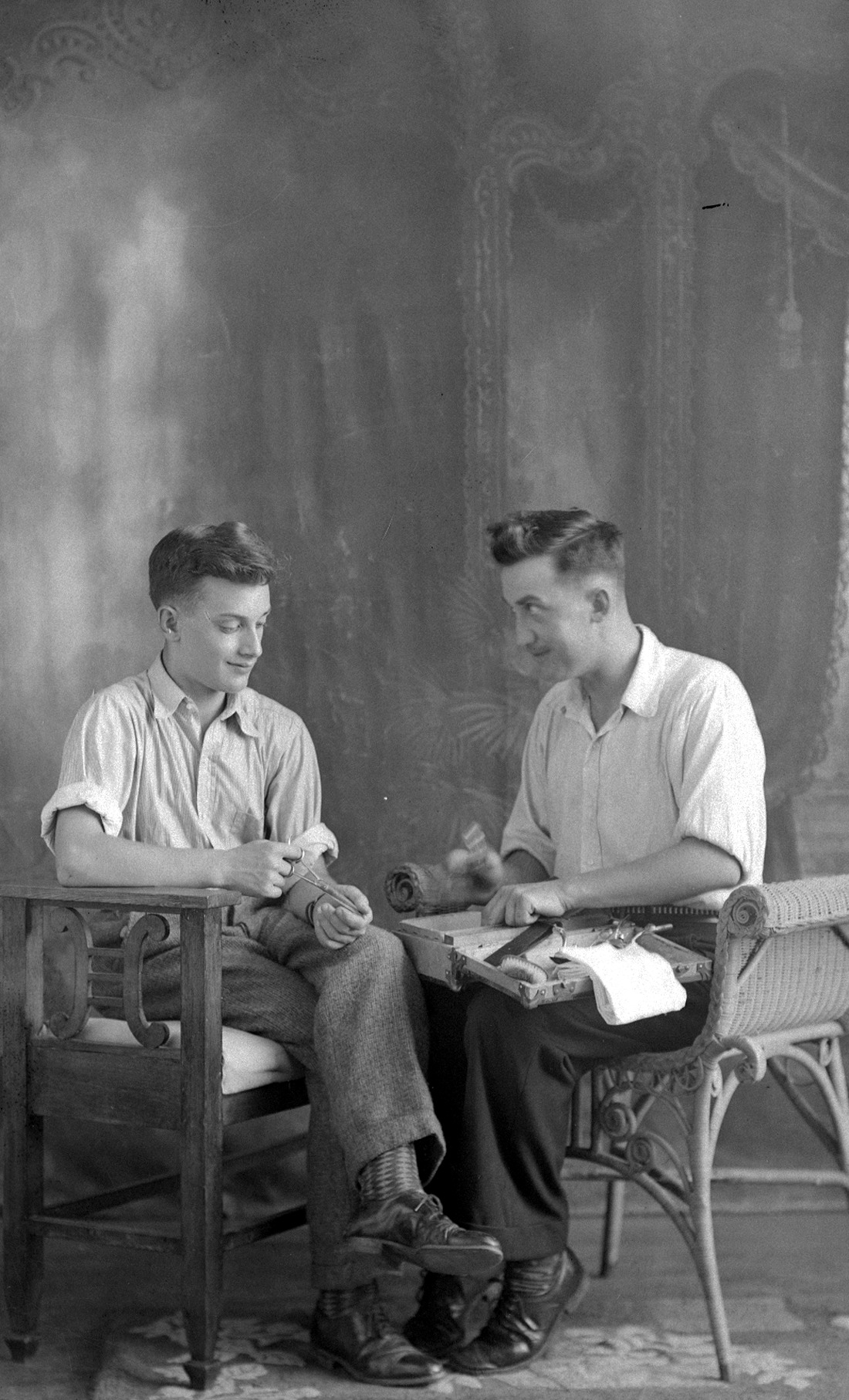

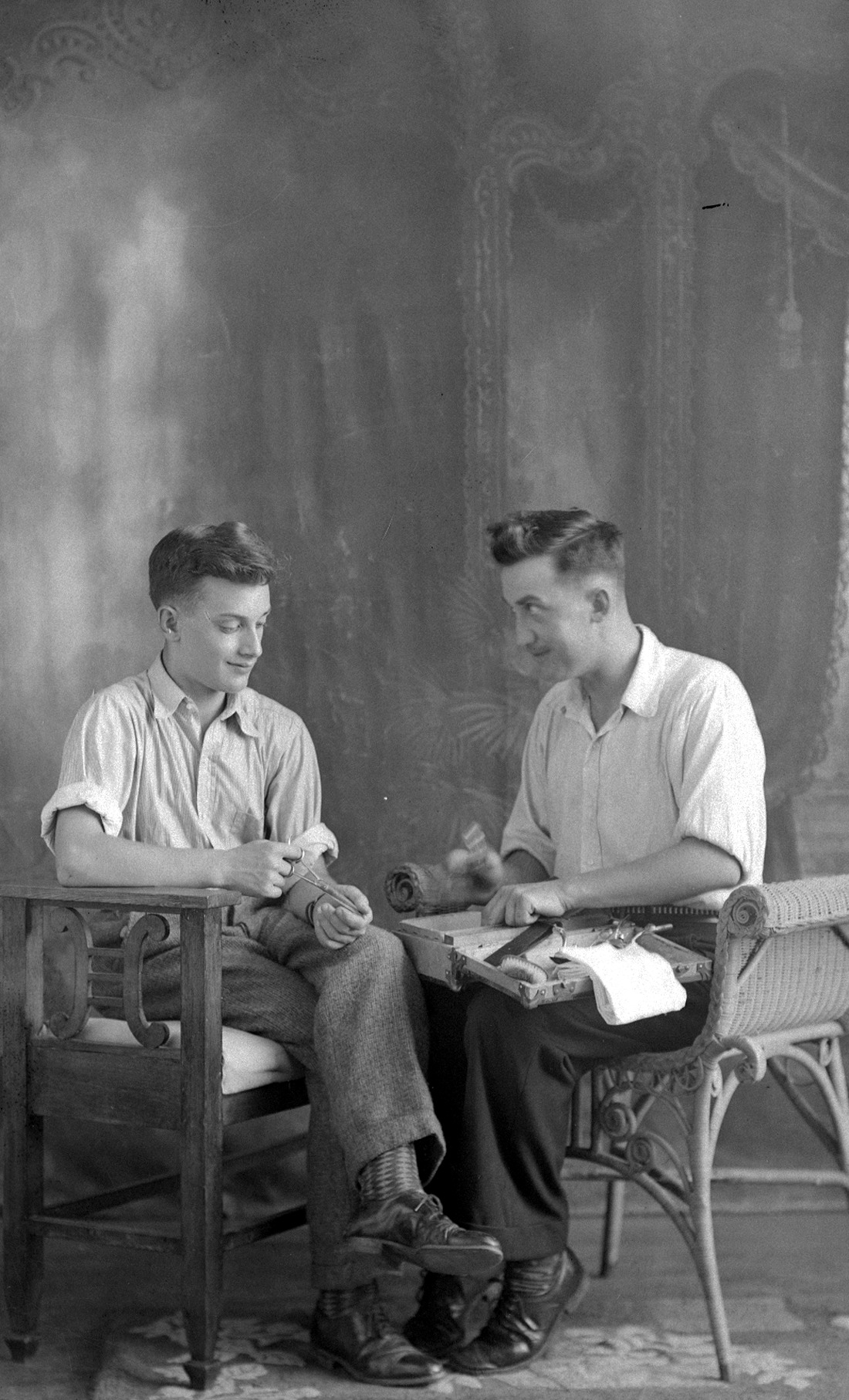

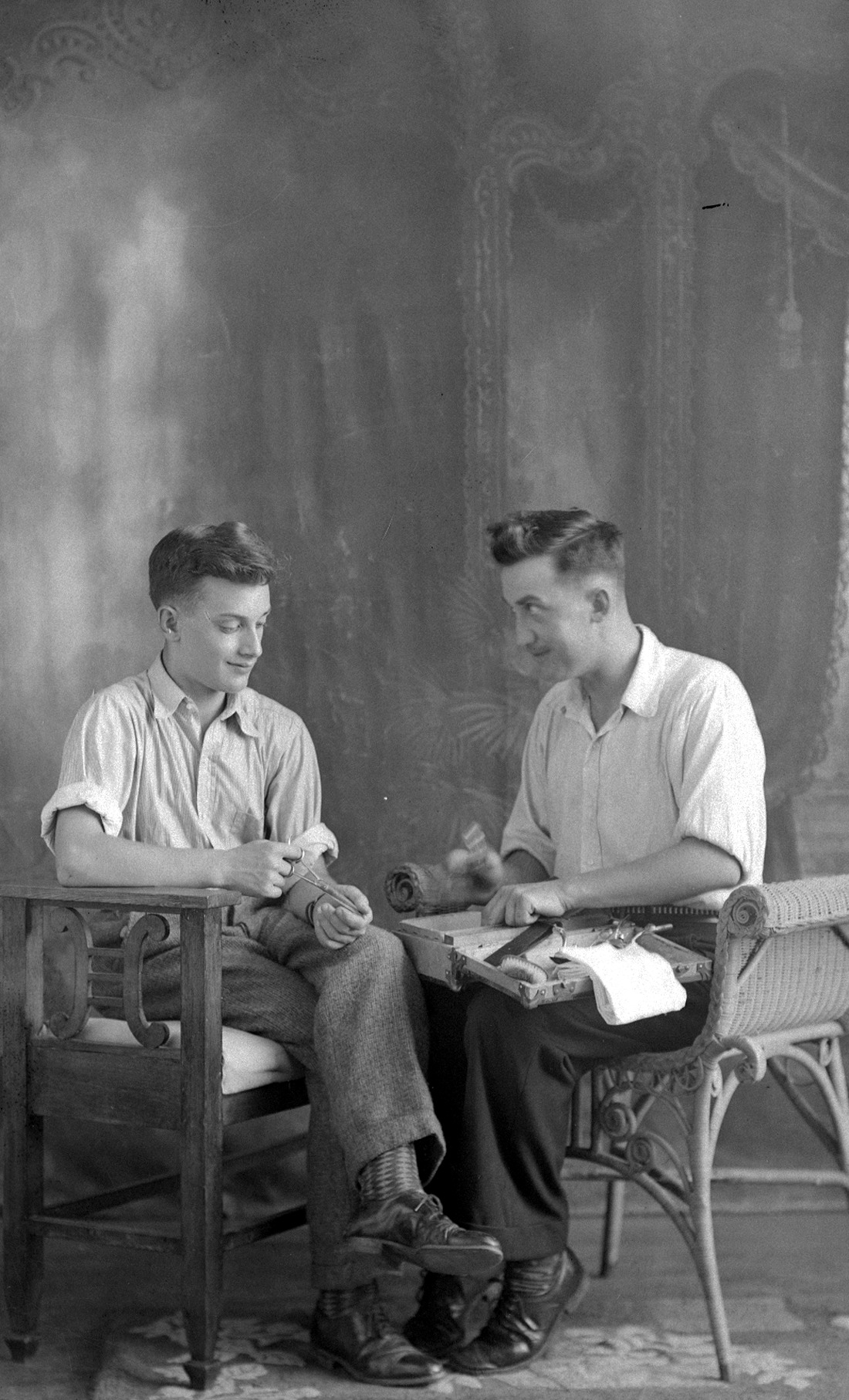

Among families of craftspeople, trades were often passed from father to son, or sometimes from uncle to nephew. Is that what this image shows? In it, Roméo Blier appears to be explaining to his nephew the use of various tools—perhaps a barber’s tools?—from his kit.

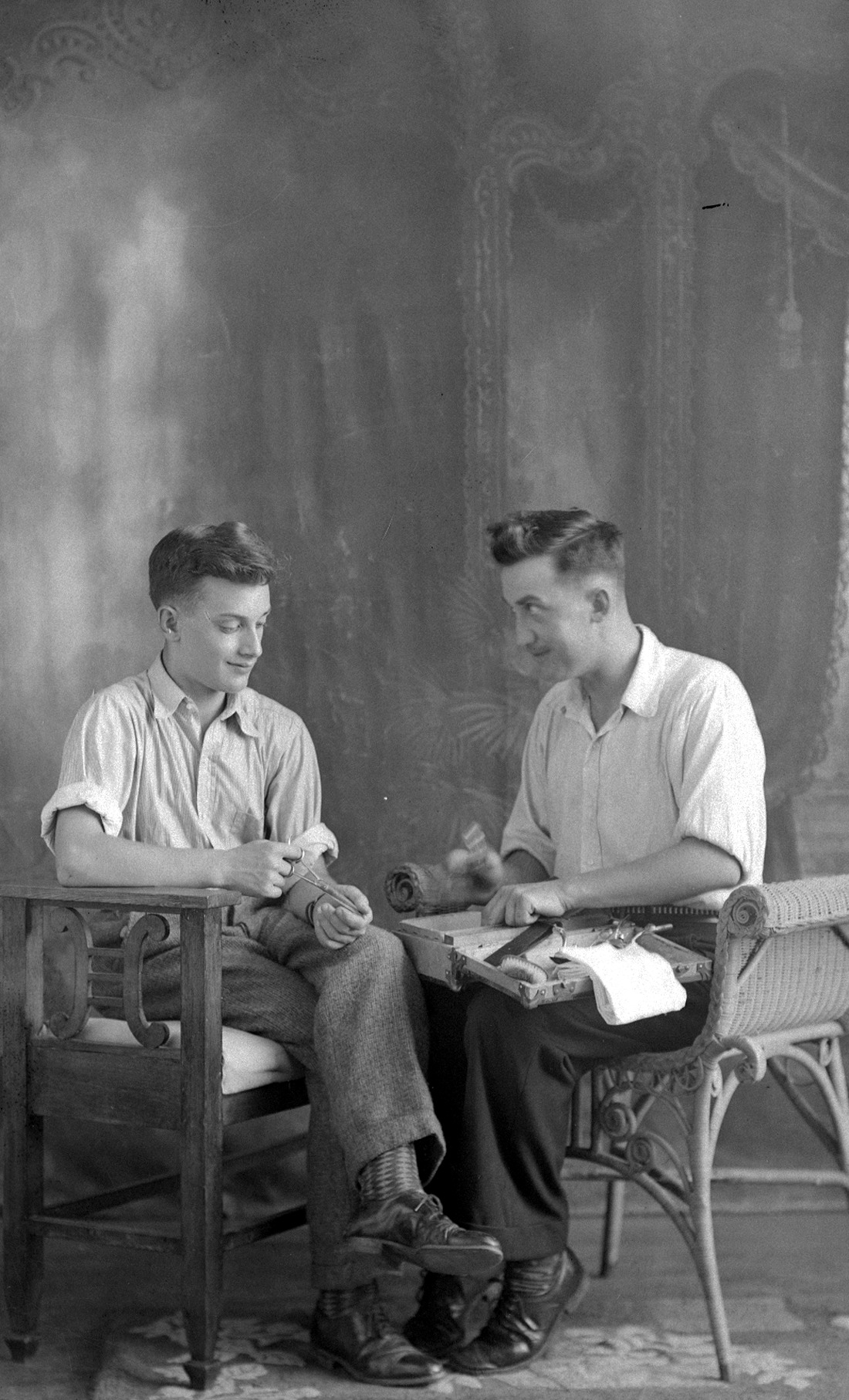

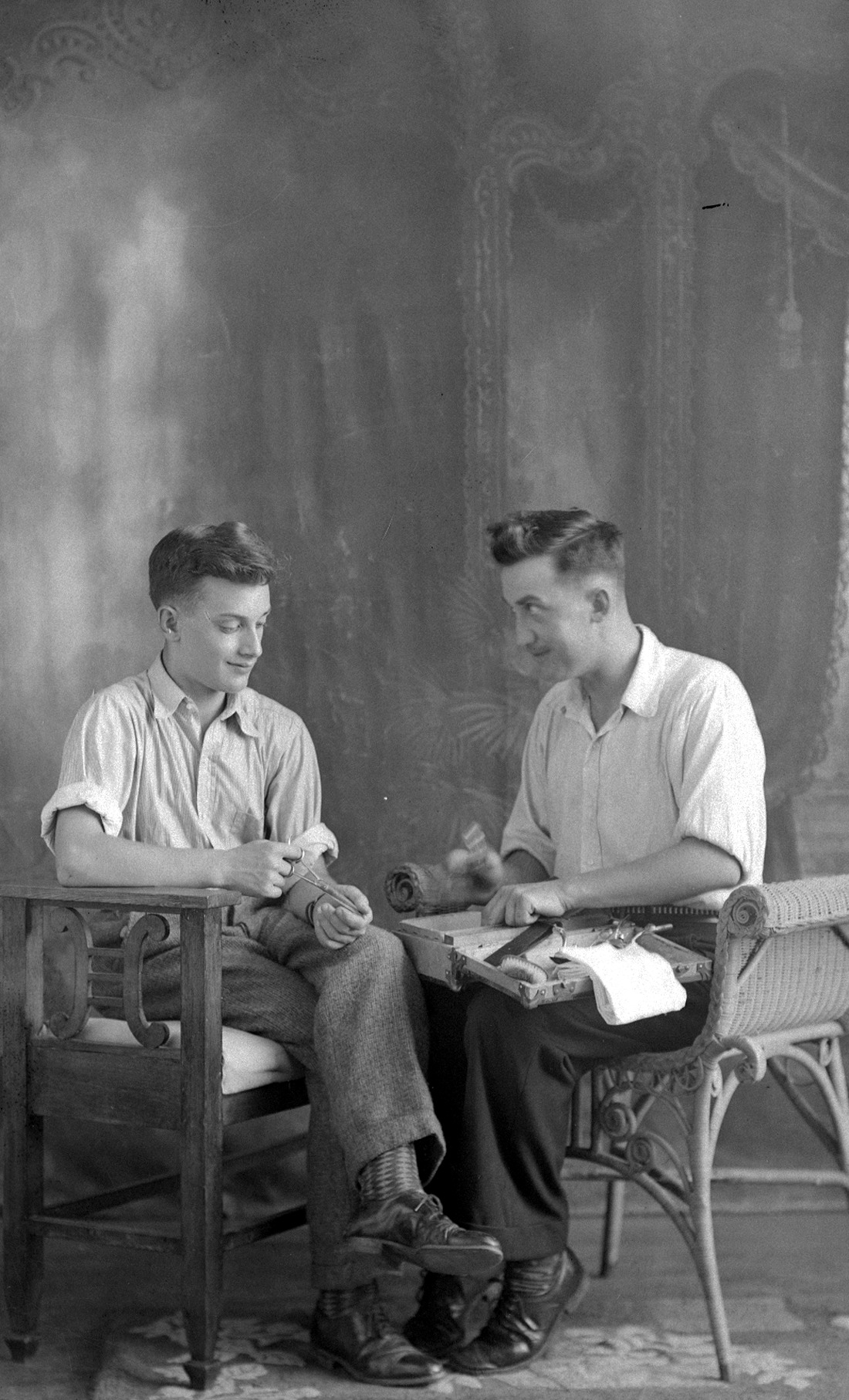

In the first half of the 20th century, cigarettes symbolized masculinity and manliness. A few of Dumont’s clients had no hesitation in posing with a cigarette in hand or between their lips. Who came up with the idea for this scene: the two friends in the photo or Dumont herself?

Jean-Baptiste Soucy is shown here on the porch of his house. In the village’s 1952 centennial album, Camille Soucy, a manufacturer and lumber merchant, pays tribute to both Jean-Baptiste and Joseph Soucy with these words: “Thanks to our Fathers. They left us a legacy of ‘Justice and Charity.’ Let us preserve it and pass it on to our children!” [our translation]

The church beadle is a crucial role in any parish. These laymen, like Donat Lamarre, are responsible for maintaining the church. They must be devout and good with their hands.

André Pelletier was a member of the Régiment de la Chaudière, which took part in World War II, including the Normandy landings. He is photographed here with his bride in 1944, the year of the D-Day invasion in which his regiment was involved. Did he go to the front? If so, we can assume this wedding portrait was taken just before his departure, since his regiment continued fighting in Europe until the end of the war.

Armed with pickaxes and shovels, the men and boys of the village built and maintained essential public infrastructure, including sewers and aqueducts. This is how towns and villages across Quebec began to modernize in the early 20th century.

The entire village took part in the Saint-Alexandre centennial celebrations. The man behind the wheel of this tractor was no doubt proud to play a part in the event and to have loaned his machine for the parade of decorated floats.

Several negatives preserved by Dumont appear to have been taken by amateur photographers who brought them in for development. In this image, a young man is pictured drinking a Red Label beer. It is part of a series of candid shots taken by two friends at a male-only worksite. It would have been surprising to see Dumont herself in such a setting like, for instance, an all-male dormitory!

In Dumont’s time, it was mostly men, like this physician, who held professional occupations: lawyers, accountants, engineers, doctors and notaries. In 1971, 35 years after this photo was taken, women still account for only 11% of those professions. But that number rose dramatically in the decades that followed, reaching 51% by 2006.

Uldéric Dumont had always taken care of his family’s firewood needs by harvesting this precious resource from his own land. Cutting firewood by hand saw was an enormous task.

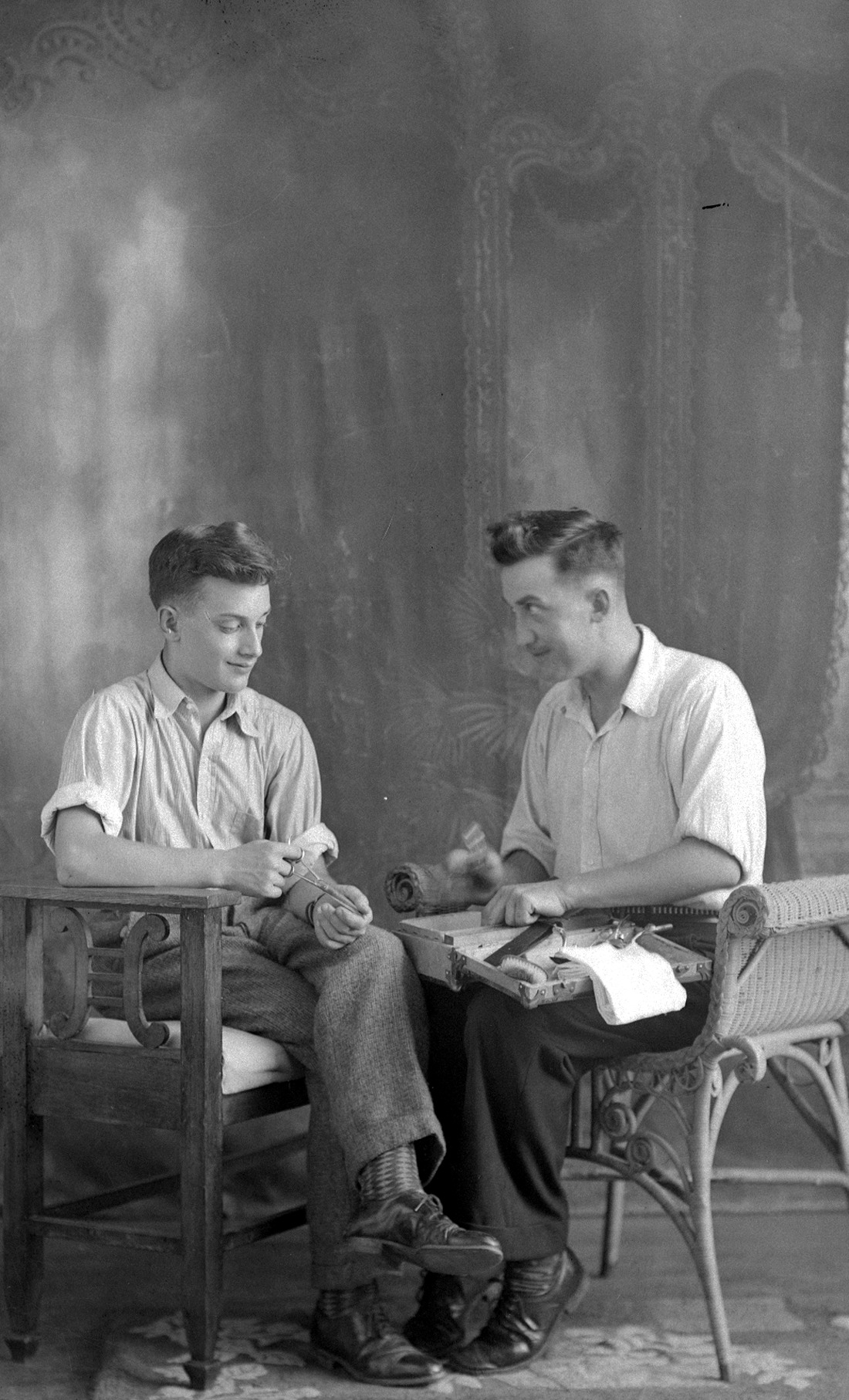

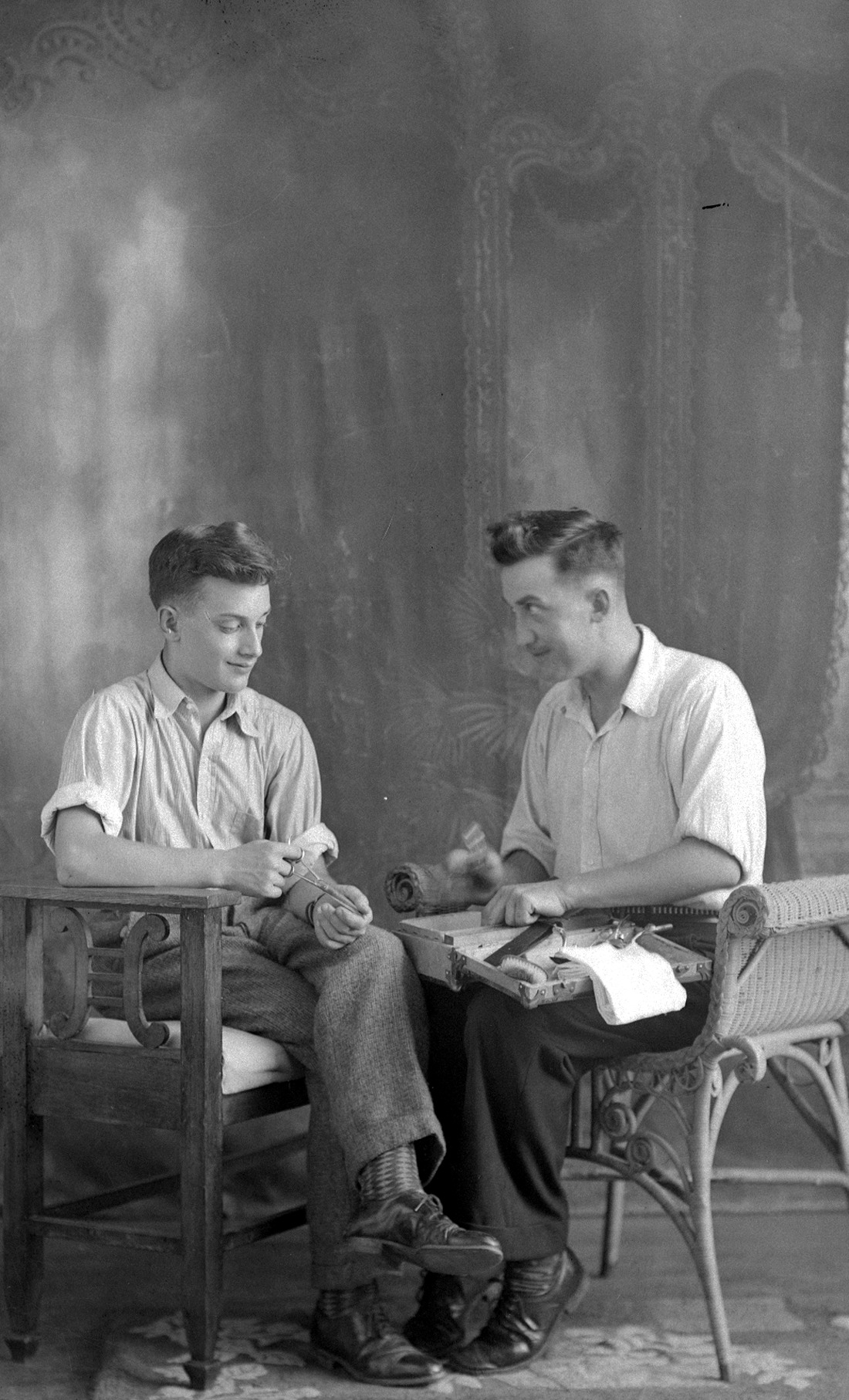

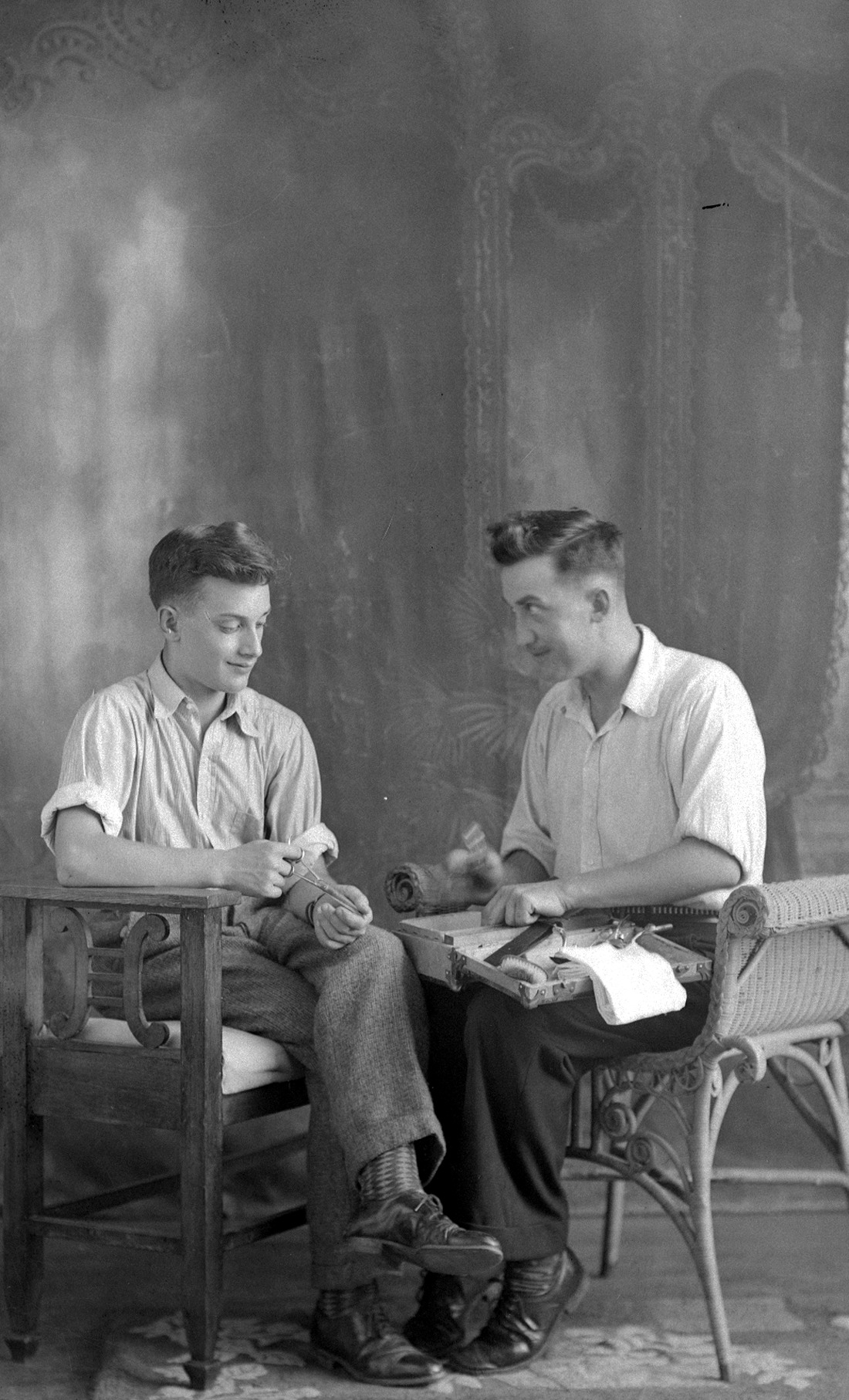

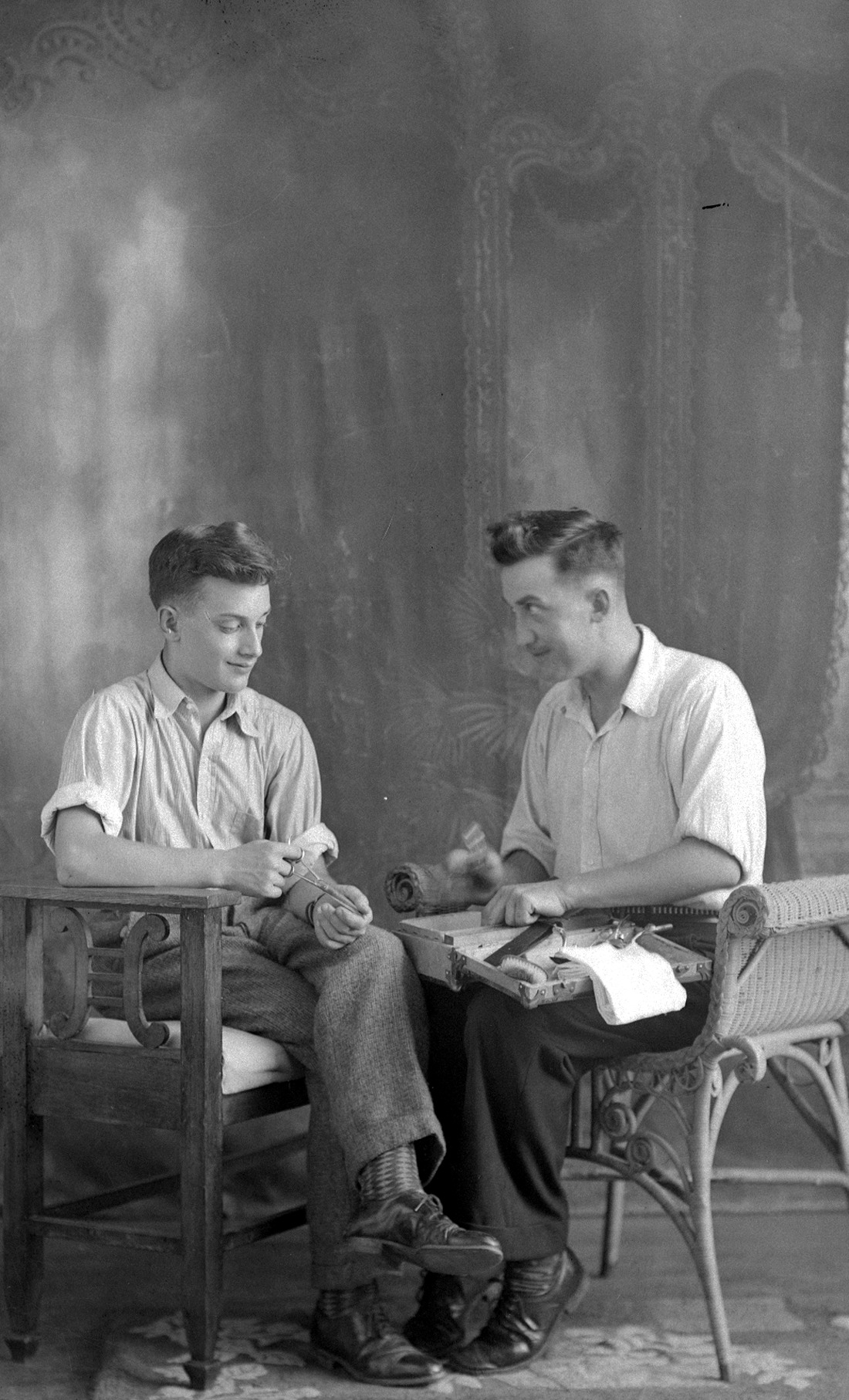

Among families of craftspeople, trades were often passed from father to son, or sometimes from uncle to nephew. Is that what this image shows? In it, Roméo Blier appears to be explaining to his nephew the use of various tools—perhaps a barber’s tools?—from his kit.

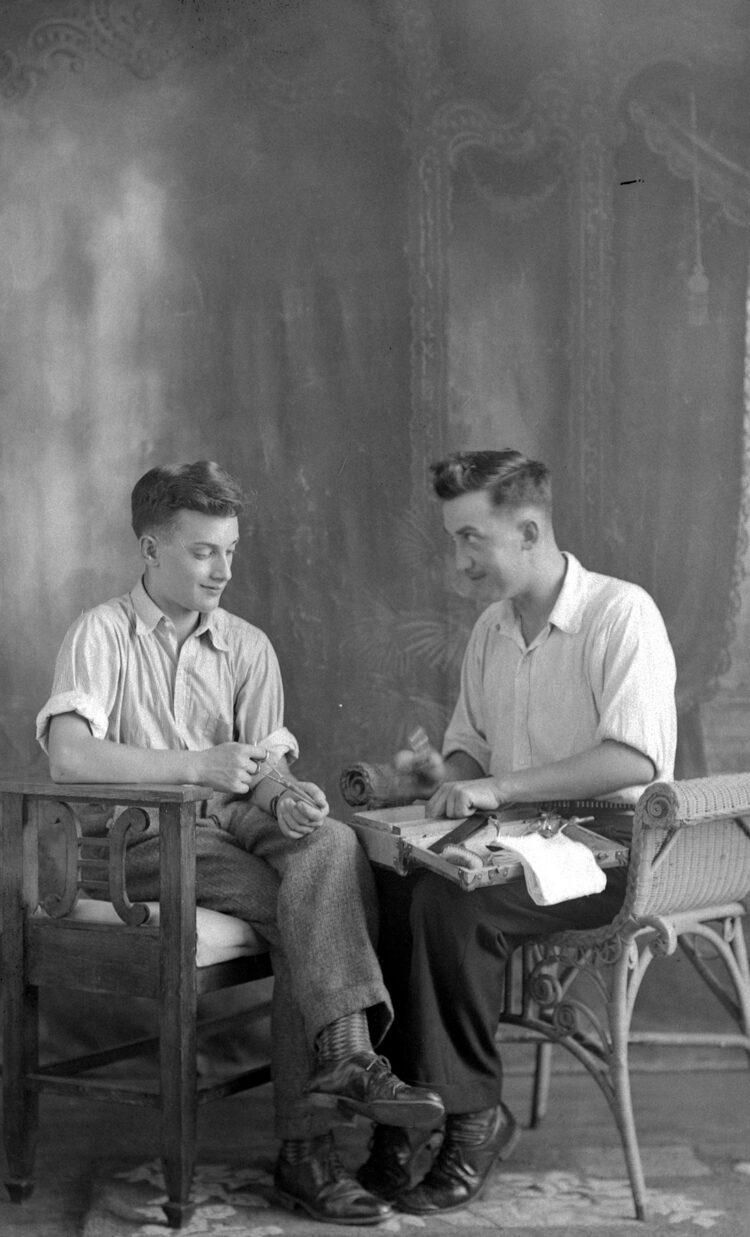

In the first half of the 20th century, cigarettes symbolized masculinity and manliness. A few of Dumont’s clients had no hesitation in posing with a cigarette in hand or between their lips. Who came up with the idea for this scene: the two friends in the photo or Dumont herself?

Jean-Baptiste Soucy is shown here on the porch of his house. In the village’s 1952 centennial album, Camille Soucy, a manufacturer and lumber merchant, pays tribute to both Jean-Baptiste and Joseph Soucy with these words: “Thanks to our Fathers. They left us a legacy of ‘Justice and Charity.’ Let us preserve it and pass it on to our children!” [our translation]

The church beadle is a crucial role in any parish. These laymen, like Donat Lamarre, are responsible for maintaining the church. They must be devout and good with their hands.

André Pelletier was a member of the Régiment de la Chaudière, which took part in World War II, including the Normandy landings. He is photographed here with his bride in 1944, the year of the D-Day invasion in which his regiment was involved. Did he go to the front? If so, we can assume this wedding portrait was taken just before his departure, since his regiment continued fighting in Europe until the end of the war.

Armed with pickaxes and shovels, the men and boys of the village built and maintained essential public infrastructure, including sewers and aqueducts. This is how towns and villages across Quebec began to modernize in the early 20th century.

The entire village took part in the Saint-Alexandre centennial celebrations. The man behind the wheel of this tractor was no doubt proud to play a part in the event and to have loaned his machine for the parade of decorated floats.

Several negatives preserved by Dumont appear to have been taken by amateur photographers who brought them in for development. In this image, a young man is pictured drinking a Red Label beer. It is part of a series of candid shots taken by two friends at a male-only worksite. It would have been surprising to see Dumont herself in such a setting like, for instance, an all-male dormitory!

In Dumont’s time, it was mostly men, like this physician, who held professional occupations: lawyers, accountants, engineers, doctors and notaries. In 1971, 35 years after this photo was taken, women still account for only 11% of those professions. But that number rose dramatically in the decades that followed, reaching 51% by 2006.

Uldéric Dumont had always taken care of his family’s firewood needs by harvesting this precious resource from his own land. Cutting firewood by hand saw was an enormous task.

Among families of craftspeople, trades were often passed from father to son, or sometimes from uncle to nephew. Is that what this image shows? In it, Roméo Blier appears to be explaining to his nephew the use of various tools—perhaps a barber’s tools?—from his kit.

In the first half of the 20th century, cigarettes symbolized masculinity and manliness. A few of Dumont’s clients had no hesitation in posing with a cigarette in hand or between their lips. Who came up with the idea for this scene: the two friends in the photo or Dumont herself?

Jean-Baptiste Soucy is shown here on the porch of his house. In the village’s 1952 centennial album, Camille Soucy, a manufacturer and lumber merchant, pays tribute to both Jean-Baptiste and Joseph Soucy with these words: “Thanks to our Fathers. They left us a legacy of ‘Justice and Charity.’ Let us preserve it and pass it on to our children!” [our translation]

The church beadle is a crucial role in any parish. These laymen, like Donat Lamarre, are responsible for maintaining the church. They must be devout and good with their hands.

André Pelletier was a member of the Régiment de la Chaudière, which took part in World War II, including the Normandy landings. He is photographed here with his bride in 1944, the year of the D-Day invasion in which his regiment was involved. Did he go to the front? If so, we can assume this wedding portrait was taken just before his departure, since his regiment continued fighting in Europe until the end of the war.

Armed with pickaxes and shovels, the men and boys of the village built and maintained essential public infrastructure, including sewers and aqueducts. This is how towns and villages across Quebec began to modernize in the early 20th century.

The entire village took part in the Saint-Alexandre centennial celebrations. The man behind the wheel of this tractor was no doubt proud to play a part in the event and to have loaned his machine for the parade of decorated floats.

Several negatives preserved by Dumont appear to have been taken by amateur photographers who brought them in for development. In this image, a young man is pictured drinking a Red Label beer. It is part of a series of candid shots taken by two friends at a male-only worksite. It would have been surprising to see Dumont herself in such a setting like, for instance, an all-male dormitory!

In Dumont’s time, it was mostly men, like this physician, who held professional occupations: lawyers, accountants, engineers, doctors and notaries. In 1971, 35 years after this photo was taken, women still account for only 11% of those professions. But that number rose dramatically in the decades that followed, reaching 51% by 2006.

Uldéric Dumont had always taken care of his family’s firewood needs by harvesting this precious resource from his own land. Cutting firewood by hand saw was an enormous task.

Among families of craftspeople, trades were often passed from father to son, or sometimes from uncle to nephew. Is that what this image shows? In it, Roméo Blier appears to be explaining to his nephew the use of various tools—perhaps a barber’s tools?—from his kit.

In the first half of the 20th century, cigarettes symbolized masculinity and manliness. A few of Dumont’s clients had no hesitation in posing with a cigarette in hand or between their lips. Who came up with the idea for this scene: the two friends in the photo or Dumont herself?

Jean-Baptiste Soucy is shown here on the porch of his house. In the village’s 1952 centennial album, Camille Soucy, a manufacturer and lumber merchant, pays tribute to both Jean-Baptiste and Joseph Soucy with these words: “Thanks to our Fathers. They left us a legacy of ‘Justice and Charity.’ Let us preserve it and pass it on to our children!” [our translation]

The church beadle is a crucial role in any parish. These laymen, like Donat Lamarre, are responsible for maintaining the church. They must be devout and good with their hands.

André Pelletier was a member of the Régiment de la Chaudière, which took part in World War II, including the Normandy landings. He is photographed here with his bride in 1944, the year of the D-Day invasion in which his regiment was involved. Did he go to the front? If so, we can assume this wedding portrait was taken just before his departure, since his regiment continued fighting in Europe until the end of the war.

Armed with pickaxes and shovels, the men and boys of the village built and maintained essential public infrastructure, including sewers and aqueducts. This is how towns and villages across Quebec began to modernize in the early 20th century.

The entire village took part in the Saint-Alexandre centennial celebrations. The man behind the wheel of this tractor was no doubt proud to play a part in the event and to have loaned his machine for the parade of decorated floats.

Several negatives preserved by Dumont appear to have been taken by amateur photographers who brought them in for development. In this image, a young man is pictured drinking a Red Label beer. It is part of a series of candid shots taken by two friends at a male-only worksite. It would have been surprising to see Dumont herself in such a setting like, for instance, an all-male dormitory!

In Dumont’s time, it was mostly men, like this physician, who held professional occupations: lawyers, accountants, engineers, doctors and notaries. In 1971, 35 years after this photo was taken, women still account for only 11% of those professions. But that number rose dramatically in the decades that followed, reaching 51% by 2006.

Uldéric Dumont had always taken care of his family’s firewood needs by harvesting this precious resource from his own land. Cutting firewood by hand saw was an enormous task.

Among families of craftspeople, trades were often passed from father to son, or sometimes from uncle to nephew. Is that what this image shows? In it, Roméo Blier appears to be explaining to his nephew the use of various tools—perhaps a barber’s tools?—from his kit.

In the first half of the 20th century, cigarettes symbolized masculinity and manliness. A few of Dumont’s clients had no hesitation in posing with a cigarette in hand or between their lips. Who came up with the idea for this scene: the two friends in the photo or Dumont herself?

Jean-Baptiste Soucy is shown here on the porch of his house. In the village’s 1952 centennial album, Camille Soucy, a manufacturer and lumber merchant, pays tribute to both Jean-Baptiste and Joseph Soucy with these words: “Thanks to our Fathers. They left us a legacy of ‘Justice and Charity.’ Let us preserve it and pass it on to our children!” [our translation]

The church beadle is a crucial role in any parish. These laymen, like Donat Lamarre, are responsible for maintaining the church. They must be devout and good with their hands.

André Pelletier was a member of the Régiment de la Chaudière, which took part in World War II, including the Normandy landings. He is photographed here with his bride in 1944, the year of the D-Day invasion in which his regiment was involved. Did he go to the front? If so, we can assume this wedding portrait was taken just before his departure, since his regiment continued fighting in Europe until the end of the war.

Armed with pickaxes and shovels, the men and boys of the village built and maintained essential public infrastructure, including sewers and aqueducts. This is how towns and villages across Quebec began to modernize in the early 20th century.

The entire village took part in the Saint-Alexandre centennial celebrations. The man behind the wheel of this tractor was no doubt proud to play a part in the event and to have loaned his machine for the parade of decorated floats.

Several negatives preserved by Dumont appear to have been taken by amateur photographers who brought them in for development. In this image, a young man is pictured drinking a Red Label beer. It is part of a series of candid shots taken by two friends at a male-only worksite. It would have been surprising to see Dumont herself in such a setting like, for instance, an all-male dormitory!

In Dumont’s time, it was mostly men, like this physician, who held professional occupations: lawyers, accountants, engineers, doctors and notaries. In 1971, 35 years after this photo was taken, women still account for only 11% of those professions. But that number rose dramatically in the decades that followed, reaching 51% by 2006.

Uldéric Dumont had always taken care of his family’s firewood needs by harvesting this precious resource from his own land. Cutting firewood by hand saw was an enormous task.

Among families of craftspeople, trades were often passed from father to son, or sometimes from uncle to nephew. Is that what this image shows? In it, Roméo Blier appears to be explaining to his nephew the use of various tools—perhaps a barber’s tools?—from his kit.

In the first half of the 20th century, cigarettes symbolized masculinity and manliness. A few of Dumont’s clients had no hesitation in posing with a cigarette in hand or between their lips. Who came up with the idea for this scene: the two friends in the photo or Dumont herself?

Jean-Baptiste Soucy is shown here on the porch of his house. In the village’s 1952 centennial album, Camille Soucy, a manufacturer and lumber merchant, pays tribute to both Jean-Baptiste and Joseph Soucy with these words: “Thanks to our Fathers. They left us a legacy of ‘Justice and Charity.’ Let us preserve it and pass it on to our children!” [our translation]

The church beadle is a crucial role in any parish. These laymen, like Donat Lamarre, are responsible for maintaining the church. They must be devout and good with their hands.

André Pelletier was a member of the Régiment de la Chaudière, which took part in World War II, including the Normandy landings. He is photographed here with his bride in 1944, the year of the D-Day invasion in which his regiment was involved. Did he go to the front? If so, we can assume this wedding portrait was taken just before his departure, since his regiment continued fighting in Europe until the end of the war.

Armed with pickaxes and shovels, the men and boys of the village built and maintained essential public infrastructure, including sewers and aqueducts. This is how towns and villages across Quebec began to modernize in the early 20th century.

The entire village took part in the Saint-Alexandre centennial celebrations. The man behind the wheel of this tractor was no doubt proud to play a part in the event and to have loaned his machine for the parade of decorated floats.

Several negatives preserved by Dumont appear to have been taken by amateur photographers who brought them in for development. In this image, a young man is pictured drinking a Red Label beer. It is part of a series of candid shots taken by two friends at a male-only worksite. It would have been surprising to see Dumont herself in such a setting like, for instance, an all-male dormitory!

In Dumont’s time, it was mostly men, like this physician, who held professional occupations: lawyers, accountants, engineers, doctors and notaries. In 1971, 35 years after this photo was taken, women still account for only 11% of those professions. But that number rose dramatically in the decades that followed, reaching 51% by 2006.

Uldéric Dumont had always taken care of his family’s firewood needs by harvesting this precious resource from his own land. Cutting firewood by hand saw was an enormous task.

Among families of craftspeople, trades were often passed from father to son, or sometimes from uncle to nephew. Is that what this image shows? In it, Roméo Blier appears to be explaining to his nephew the use of various tools—perhaps a barber’s tools?—from his kit.

In the first half of the 20th century, cigarettes symbolized masculinity and manliness. A few of Dumont’s clients had no hesitation in posing with a cigarette in hand or between their lips. Who came up with the idea for this scene: the two friends in the photo or Dumont herself?

Jean-Baptiste Soucy is shown here on the porch of his house. In the village’s 1952 centennial album, Camille Soucy, a manufacturer and lumber merchant, pays tribute to both Jean-Baptiste and Joseph Soucy with these words: “Thanks to our Fathers. They left us a legacy of ‘Justice and Charity.’ Let us preserve it and pass it on to our children!” [our translation]

The church beadle is a crucial role in any parish. These laymen, like Donat Lamarre, are responsible for maintaining the church. They must be devout and good with their hands.

André Pelletier was a member of the Régiment de la Chaudière, which took part in World War II, including the Normandy landings. He is photographed here with his bride in 1944, the year of the D-Day invasion in which his regiment was involved. Did he go to the front? If so, we can assume this wedding portrait was taken just before his departure, since his regiment continued fighting in Europe until the end of the war.

Armed with pickaxes and shovels, the men and boys of the village built and maintained essential public infrastructure, including sewers and aqueducts. This is how towns and villages across Quebec began to modernize in the early 20th century.

The entire village took part in the Saint-Alexandre centennial celebrations. The man behind the wheel of this tractor was no doubt proud to play a part in the event and to have loaned his machine for the parade of decorated floats.